Being Participants, Not Spectators

Idaho’s growth in inclusive outdoor recreation reaches Teton Valley

Options for people with disabilities to engage in outdoor recreation were once scarce across Idaho, but in the past two decades, organizations have emerged to support these athletes. Locally, Valley Adaptive Sports is bringing in new ways for athletes to enjoy all of the recreational choices in Teton Valley, in both summer and winter.

Joe Stone sat in his handcycle at the top of the Bridger Gondola. It was June 2022, and I was in a gaggle of journalists there for the opening of Deepest Darkest, Jackson Hole Mountain Resort’s intermediate, adaptive downhill mountain bike trail. The adaptive athlete and mountain biking instructor was giving a lot of directions, talking about side hits and where to shed speed.

“There are some really steep berms,” he said. “Watch out for the compression at the bottom.”

Compression? Wasn’t this an adaptive trail? I admittedly didn’t know much about adaptive biking and even less about accessible trails, but I’d assumed, without much basis, that the ride would be a bit easier than a non-adaptive trail. Journalists, professional mountain bikers, and resort representatives followed Joe down a wide, machine-groomed trail that gave ample room for his three-wheeled steed. After a very fun banked turn, we regrouped: Ahead, a small step-down jump led into an extremely steep berm that dumped riders full speed across an ephemeral creek rivulet before launching them off a lip and back into the trees.

“All right, follow me,” Joe yelled as he dropped in, careening into the turn and going three wheels in the air over the lip. With dusty smiles, we followed through several more big turns back to the base area. Filled with small jumps, side hits, and technical sections (all with optional ride arounds), the trail was engaging whether you were on two wheels or three.

Deepest Darkest is just one example of local entities not just making space for athletes with disabilities, but making trails that are accessible to all.

This trail has been celebrated for working for every type of rider, adaptive or not. Joe, the former executive director of Jackson Hole-based Teton Adaptive who now runs Dovetail Trail Consulting, was pivotal in ensuring the trail accomplished that goal. Joe’s consulting firm provides solutions for adaptive recreation opportunities in national parks, resorts, and outdoor hubs.

At Grand Targhee Resort, while the extensive mountain biking trail system does not have a trail specifically designed and built for adaptive riders, most all of the gravity and cross-country trails are accessible for adaptive equipment, the resort says.

“For the past few years, we have partnered with Teton Valley Trails and Pathways, Teton Adaptive, and Valley Adaptive Sports (VAS) to facilitate adaptive group rides and clinics on our trails, specifically around the Wydaho Rendezvous Teton Bike Festival,” says Jill Gaylord, marketing director at the resort. “Wydaho has simultaneously grown to a point where we host the largest adaptive component of any mountain bike festival in North America.”

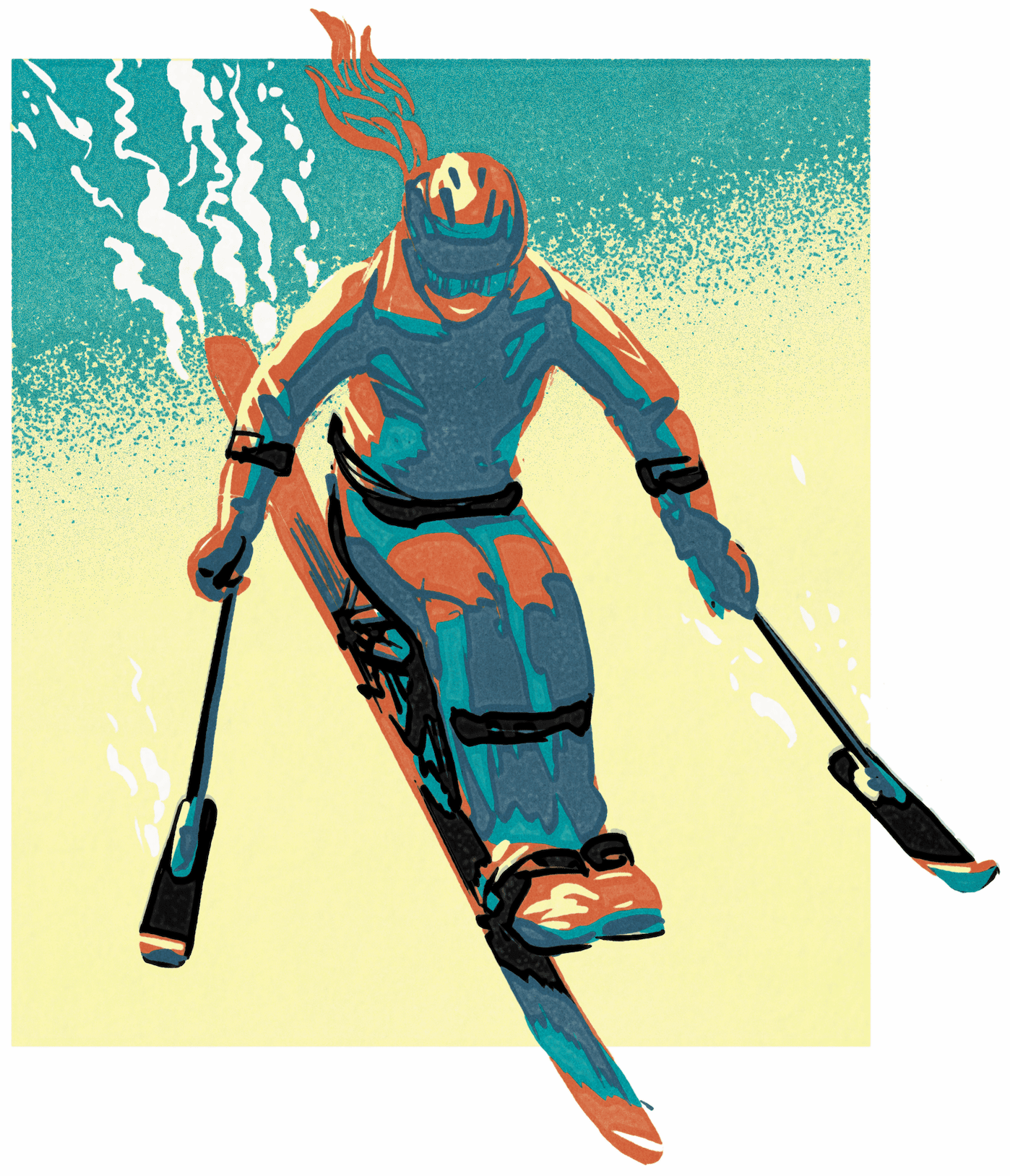

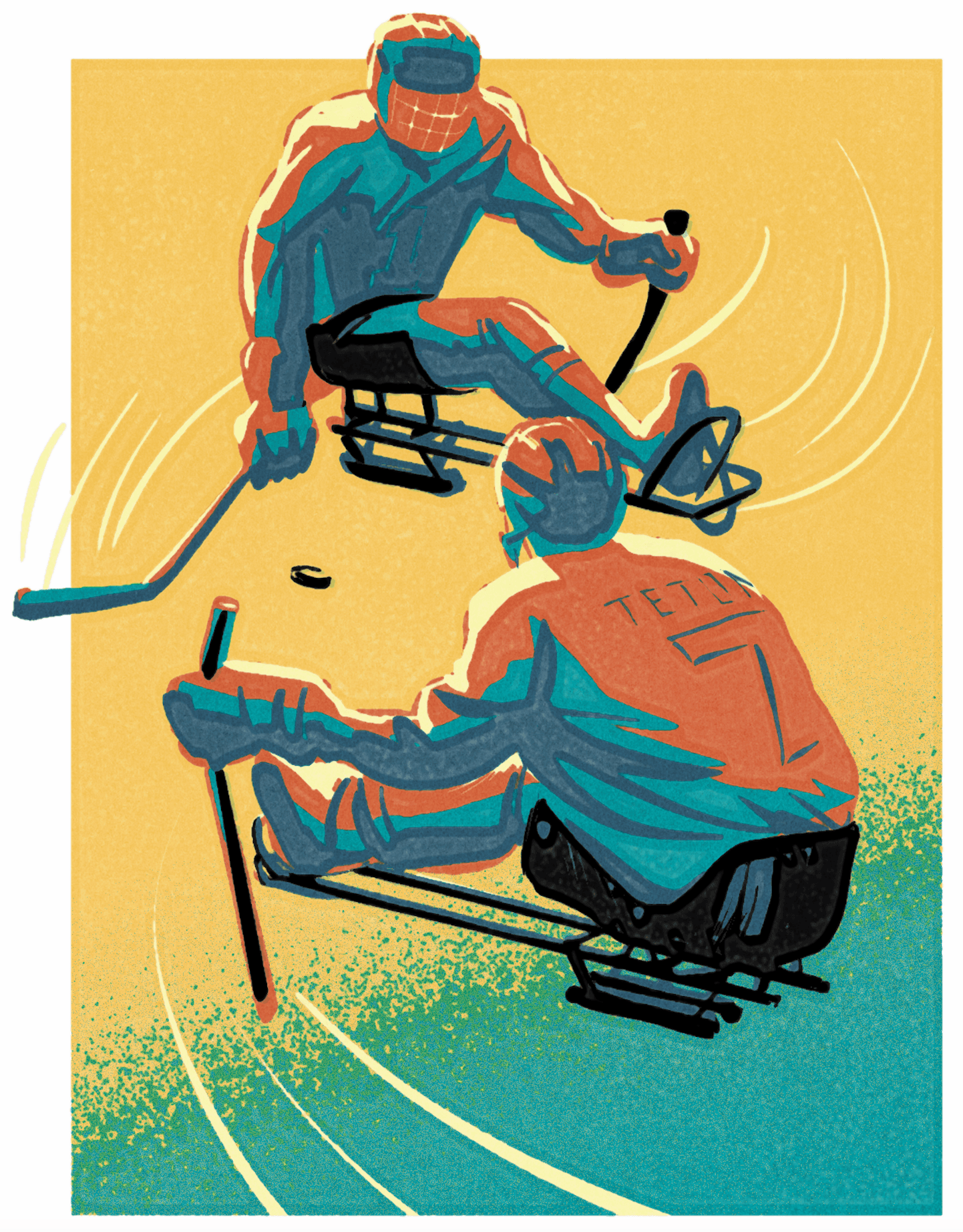

From the twelve-mile, adaptive-accessible Southern Valley mountain bike trail system near Victor to support from the relatively new nonprofit Valley Adaptive Sports, sit-ski lessons and adaptive-accessible biking at Grand Targhee, and sled hockey games at Kotler Ice Arena, the list of local options for adaptive athletes is growing.

“Adaptive sports has evolved as the equipment has become more available, more capable, and more comfortable,” says VAS executive director Nate Carey. “Sled hockey, golf, bicycles, skis, swimming equipment, and more are now available like never before.”

And advocates think the momentum will continue to build, starting with statewide access.

Access in Idaho

Muffy Davis never expected a ski-racing fall to leave her in a wheelchair. “I always knew there was risk ski racing,” she says. “But the idea of a life-altering injury was never even in my wheelhouse.” However, after crashing through the course-side fencing on a training run at the age of sixteen in the late 1980s, Muffy sustained a back injury that left her paralyzed from the waist down. A Sun Valley native, she rehabbed in Colorado, but when she returned home, skiing again seemed out of the question.

Options for adaptive sports at the time in Idaho ranged from limited to nonexistent. Muffy went to Winter Park, Colorado, for sit-ski lessons, but she fell a lot and struggled, often ending up in a ski patrol toboggan. She left Idaho to attend college in California, where she met instructor Marc Mast, who told her she’d been skiing on the wrong equipment for her injury. “What works for a double amputee is not going to work for a T5/6 paraplegic,” says Muffy, who went on to win seven Paralympic medals as a cyclist and skier. “In a lot of different sports, not all, it’s very sports-specific and it’s very disability-level specific.”

In a fortuitous move, Marc came to Hailey for a summer and ended up moving to the Wood River Valley, planting the seeds for the growth of adaptive outdoor recreation across Idaho. Until then, people with disabilities didn’t have options in Sun Valley, or anywhere else in the state. Marc’s expertise was the missing piece. Muffy and others in the area started Higher Ground, an education nonprofit dedicated to adaptive athletes, with Marc as an instructor. At first, Higher Ground was a chapter of Disabled Sports USA (now called Move United), a nonprofit that promotes the growth of adaptive sports up through levels that include the Paralympics.

“It started in 1999,” says Jeff Burley, Muffy’s husband and Higher Ground’s director of compliance and advancement. “It was definitely behind the curve, compared to something like Title X.”

Adaptive sports can take many forms. In areas with more facilities and larger populations, options might focus on court and field sports, like basketball or football, while in mountain towns choices skew toward outdoor recreation, including cycling, skiing, and climbing. No matter where they take place, adaptive programs exist in a collaborative web that relies on expertise, funding, and support from regional and national entities, especially in their early years. Higher Ground was part of Disabled Sports USA; it is now a juggernaut in its own right, leading hundreds of lessons a year for skiers, riders, and bikers, along with a thriving network of weeklong programs for veterans.

As evidenced by Muffy’s need to recruit Marc from California to Sun Valley two decades ago, Idaho has not historically had a robust network of such programs. That’s changing, in both Teton Valley and the state’s largest population center, Boise. Challenged Athletes Foundation (CAF), a national nonprofit that promotes and facilitates adaptive sports by putting on camps and clinics and giving athletes grants for travel and lessons, now has an Idaho chapter.

“We’ve done a handful of court sports, but we really try to focus on the Idaho sports, if you will, which is outdoor recreation,” programs director Heather Lopez says.

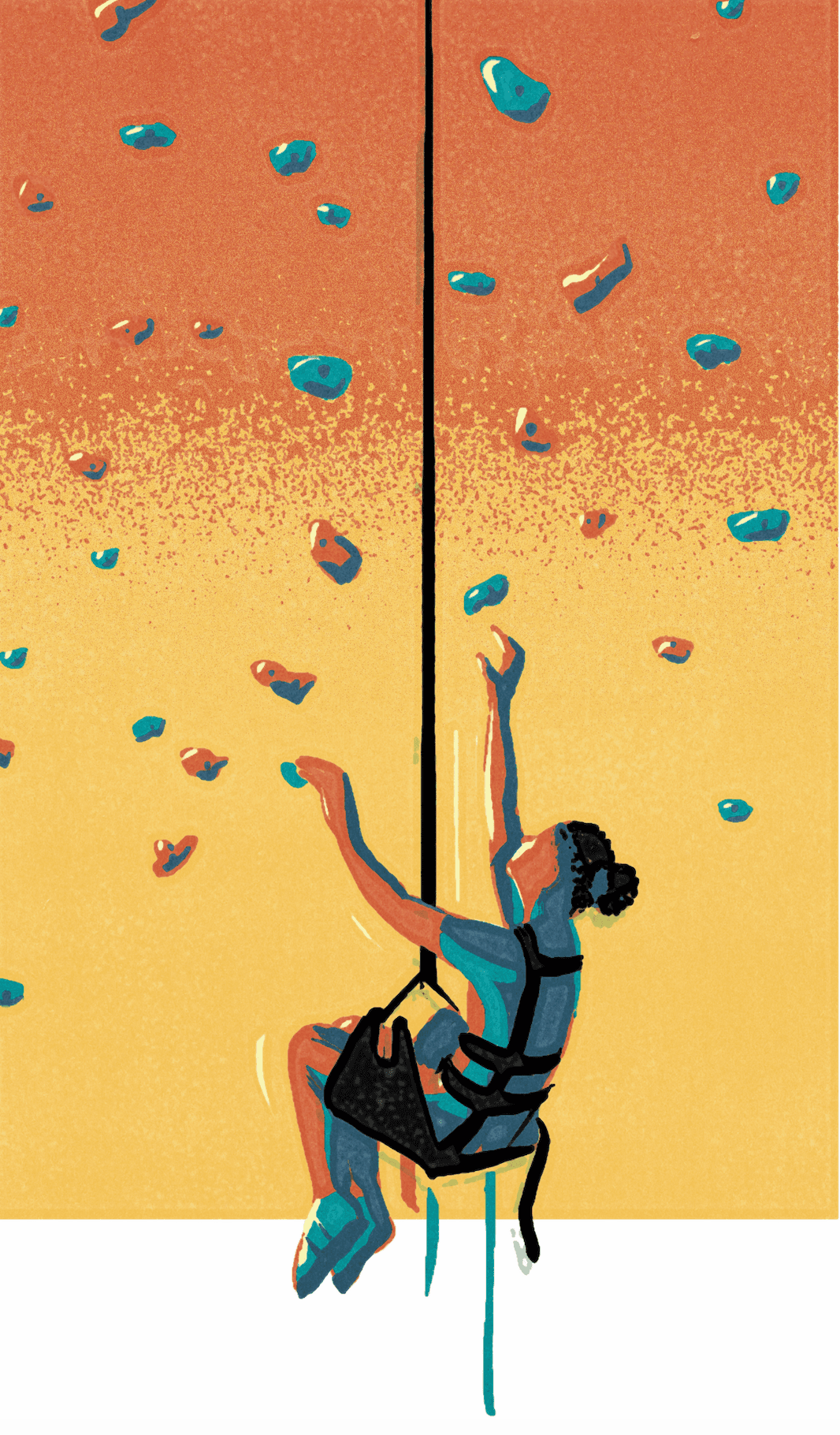

The organization is housed in the new Idaho Outdoor Fieldhouse, an adaptive sports colossus in Boise funded and built by the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation. In addition to a large gym with fitness equipment, the fieldhouse features rock climbing and bouldering areas; a swimming pool; a Ninja Warrior-type course overhanging said pool; and outdoor areas with a variety of walking surfaces (think boulders, uneven trails). Two other nonprofits use the campus: Summit Hyperbarics and Wellness, a clinic that offers hyperbaric chamber treatments, and Mission43, which provides programming for wounded veterans.

Opened in November 2023, the fieldhouse, for now, isn’t a gym that adaptive athletes can pop in and out of. Instead, it hosts group fitness classes and lessons with adaptive instructors. “Our mission is really about empowering people through sport,” Heather says. “I think sport is almost secondary, and it’s really the community that’s the most important.”

Adaptive reach in the valley

That sentiment extends past CAF’s home in Boise all the way to a bitterly cold January 2024 day at Grand Targhee Resort. Buoyed by CAF’s funding and logistical support, and a group of instructors from Higher Ground, a dozen adaptive athletes descended on the resort for the Challenged Athletes Foundation East Idaho Ski Camp. They included Idaho Falls resident Chris Hayes, who returned to the slopes for the first time in more than twenty years.

The ski camp didn’t go quite as VAS executive director Nate Carey had planned. “This was supposed to be four days,” Nate told me as we gathered at the adaptive program building at Grand Targhee the day before Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. He’d envisioned athletes from around the state participating in a festival of sorts, featuring equipment demos and clinics for instructors and lessons for all types of adaptive athletes. The weather, however, had other plans.

Blizzard conditions kept many from making the trip at all, and below-zero temperatures made keeping wheelchair-bound skiers warm difficult, so Nate trimmed the event to just one day. Despite the weather, roughly a dozen athletes showed up for ski and snowboard lessons, mostly in the afternoon. Following lunch, Chris’ family wheeled him out to a Snow’Kart, a type of sit-ski with two levers that control a pair of skis; or, in a new model developed at the University of Utah, featuring sip-and-puff technology that would allow a person who is quadriplegic to control it using their mouth.

Bundled up and with a helmet on, Chris sat patiently as Higher Ground instructors adjusted straps and checked his gloves. “This is your Ferrari for the day,” Nate told him. Smiling nervously, Chris nodded in reply.

In January 2001, Chris, then eleven, came down with the flu. The disease spread to his trachea, cutting off airflow and depriving his brain of oxygen. He went into a coma for a month, and when he awoke, he had lost much of his ability to move and speak. For an active kid who skied, biked, and played many traditional sports, the change was earth-shattering. “Prior to getting sick he wasn’t much of a spectator; he was a participant,” says his dad, Tom. “Now he doesn’t get a lot of opportunities anymore to participate, except as a spectator.”

Flanked by his entire family and two instructors helping to clear the run and control the Snow’Kart, Chris skidded hesitantly across the slope near the bottom of the Shoshone Lift, finishing each turn to a stop, learning the intricacies of the vehicle. His smile still looked nervous.

At the top of Shoshone, his family gathered—dad, sister, nieces, brother-in-law. “I want to ski with Chris,” one his nieces yelled to anyone in her vicinity. And then he dropped. In a herky-jerky clump, the clan skidded down Little Big Horn behind Chris, their iPhones raised to capture their first run as an entire family in two decades. Through the broad, shallow expanse of the run’s middle, Chris picked up more speed, becoming comfortable with the turns. By the time he took the cat track to the lower section of Bobsled, one might have taken him for a celebrity as he linked flowy turns while his family lined the run, cheering and snapping photos.

When he cruised past the maze to get back on the lift, Chris was still smiling, but no longer nervously. “Afterward, I was feeling pure joy as it felt so good to be back in my former domain for an afternoon,” he told me later in an email. “It had been at least twenty-three years since I last skied. It was an incredible experience. Although different, it was familiar, familiar in a way that used to give me such joy, and doing it again made me so happy.”

Working toward equality

“I would like to see Teton Valley continue to increase accessible recreation because this attitude benefits everyone,” Nate says. “Trails and pathways are being improved, and we are expanding our recreation offerings, our partnerships, and our equipment cache. Everyone enjoys getting out in Teton Valley. We look forward to being right there in the mix.”

People with disabilities in Teton Valley contend with snow on the ground half the year, which can make life more difficult. And they have historically lacked services like what VAS provides. Nate and the organization are continually working to change that.

“I’d like this to be a yearly event,” he said at the January adaptive camp, despite the meteorological challenges. In just two years, Nate has broadened the scope of what VAS offers, buying cross-country skiing equipment, starting sled hockey in Idaho Falls and Victor, working with the Teton Rock Gym to buy specific harnesses for inclusive climbing nights, and participating in the Wydaho Rendezvous Teton Bike Festival, which includes adaptive lessons and rides. It’s a big endeavor, given that each sport requires its own equipment, and each type of injury might, as well, but the community has allowed Nate to steadily grow his stable of gear. “It’s little baby steps,” he says, “but we’re really excited to have all the support from several nonprofits that we’re happy to call partners.”

Running as an undercurrent throughout the work on adaptive sports in the valley and across the state: a message of dignity and accessibility. As Nate says, athletes with disabilities don’t necessarily want to be an example of perseverance; rather, they just want to enjoy the same activities that have drawn so many to this area. They want lessons and equipment tailored to their injuries and bodies. They want bike trails like Deepest Darkest, ones that are wide enough for handcycles, but engaging and fun enough to make a journalist and avid mountain biker like me take notice. They want to meet other athletes with disabilities, and some want the chance to enjoy the outdoors not in a group setting, but perhaps with just an instructor or a friend.

In other words, they want opportunity. With the progression of local nonprofits, expanded cutting-edge gear, and a statewide effort to create more resources, the opportunities are growing.