What Happens When You Flush?

Regardless of where you live, you’d probably rather not give a second thought to where your wastewater goes. But maybe you should. Driggs’ wastewater plant has been giving city officials headaches for years due to permit violations. After a federal lawsuit and subsequent settlement, a new plant is on the horizon.

Everybody poops.

Legacy family on their homestead? Yep. Renters stacked six deep in a ski bum house? Them, too. Tourists here for a fly-fishing weekend? Even they must “own the throne” from time to time.

Almost no one thinks about what happens when we flush the toilet. It’s indecent. One flick of the handle and that thing we all do but don’t talk about is out of our minds. However, that waste and water need to be filtered, cleaned, and sent back into the natural system. For decades in Teton Valley, that process has been broken.

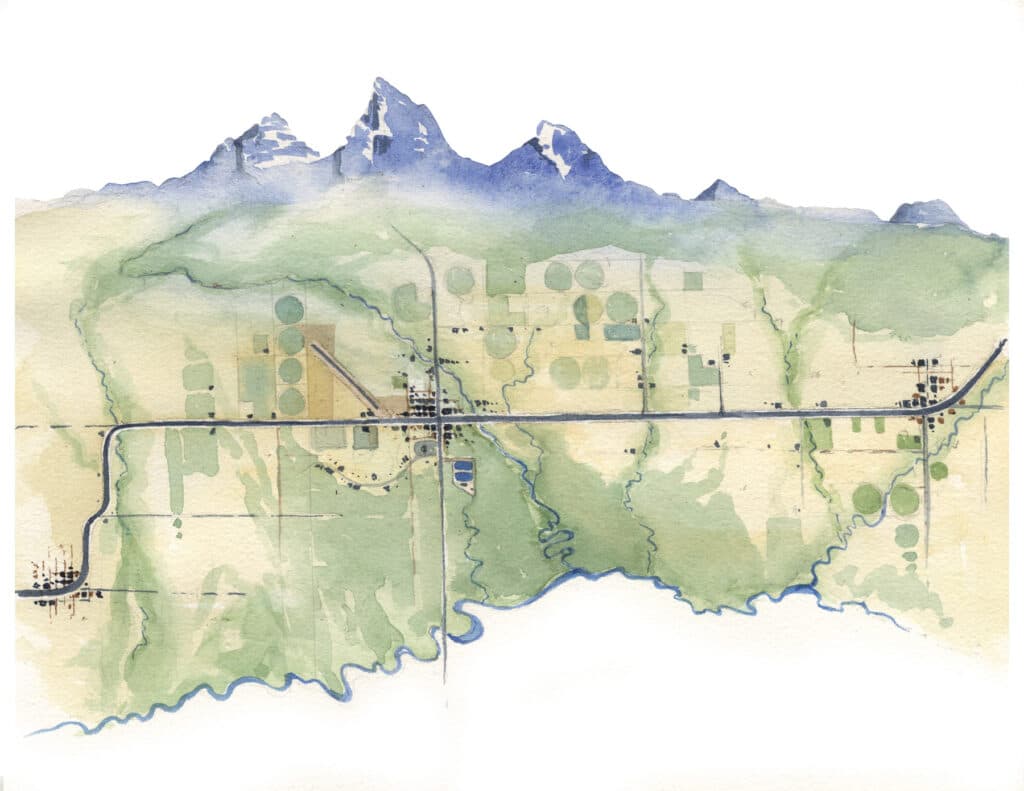

For years Driggs’ wastewater treatment plant, which currently services Driggs, Victor, and some of the cities’ surrounding developments, has run afoul of its Idaho Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (IPDES) permit, a document granted by the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality (IDEQ) that governs the amount of pollutants such plants release into waterways.

The Driggs facility is not alone. In a 2023 report, the Idaho Conservation League (ICL) found that eighty-four out of 112 wastewater plants in the state had at least one violation between 2019 and 2021. Driggs was one of nine that had more than forty.

As Will Tiedemann, ICL’s regulatory conservation associate and the report’s author, puts it, “It’s something that’s in everyone’s backyard, more or less, that often goes unnoticed, but does play a significant part in water quality.”

Bathroom Biology

Like about half of Teton Valley’s dispersed lots, my property keeps its wastewater. Adjacent to the house is an underground septic tank, into which my drainpipe empties. Inside the tank, solids settle to the bottom, bacteria and microorganisms eat the waste, and clean water is expelled through a series of buried, perforated pipes. Come the middle of the dry summer, the leach field, with its constant “watering,” is the greenest part of my yard.

Despite the potential for queasiness caused by the idea of treated sewage water in one’s yard, septic tanks are generally effective. “Tanks, in theory, should not pose any risk to water quality,” says Peter Adams, IDEQ’s onsite wastewater coordinator. “It’s only a failing tank that poses a risk.”

Therein lies the rub. If you live in Driggs or Victor, you pay a monthly fee for someone else to deal with the waste and water-quality risk, whereas those with septic tanks need to have them pumped every three to five years.

“When they get over-full or are not serviced, then they’re not decomposing and breaking down the waste, and they’re leaching raw sewage through that leach field,” says Will Stubblefield, senior director of programs at Friends of the Teton River (FTR). The nonprofit has for years regarded septic tanks as potentially creating nonpoint source pollution (contamination that doesn’t spring from one definable cause). In an ideal world, Peter says, tanks wouldn’t be a risk, but Idaho has no laws regulating septic tank maintenance. So, it is incumbent on homeowners to follow recommended guidelines.

Groups like FTR worry that this honor system carries a high risk of failure. In the past, FTR has helped homeowners cover the cost of septic tank maintenance, and the organization provides educational materials. The group concluded that in areas with enough population to justify the cost, wastewater treatment plants can be a more efficient, effective way to handle sewage.

In the late 2000s, the Driggs City Council started looking into building a new treatment plant. One with a little more firepower than its existing lagoon system, which the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) had flagged as polluting. The council chose Aquarius Technologies’ Multi-Stage Activated Biological Process (MSABP) system, which was untested in Idaho. In 2013 the former weekly newspaper, Valley Citizen, described it as “the most cutting-edge wastewater treatment plant in the state.”

When wastewater comes into an existing plant, it is first filtered for inorganics—jewelry, rocks, trash, cell phones—then sent to smaller filters that remove anything larger than one millimeter. Everything collected is sent to the landfill. The water then makes one pass through the MSABP system, a series of concrete basins filled with polypropylene cloth that Driggs Public Works Director Jay Mazalewski calls “New York City for the biology,” or the bugs and bacteria that eat everything. It leaves as relatively clear water before hitting a plate settler that pushes out any remaining bug carcasses. Lastly, UV lights disinfect the water before it’s discharged into a tiny, trickling tributary of Woods Creek, which eventually flows into the Teton River.

Two purported benefits of the MSABP system were a reduction in sludge—the bodies of the biology that accumulate—and required staffing. According to Jay, that promise of no sludge never panned out. Aquarius was founded in 2006, so it and the MSABP were relatively new. For reasons that are still not clear, the MSABP plant never lived up to expectations.

“I have spent the last seven years trying to figure out how to make the existing facility work,” Jay says, although he thinks the valley’s cold groundwater and influent may have slowed the process of the ammonia-eating bacteria.

Aquarius Sales Manager Bryen Woo says the company has installed MSABP systems in other cold-weather climates, including Wayne, Nebraska, and three in Colorado. Wayne’s Public Works Director Casey Junck confirmed his city has enjoyed permit compliance. Bryen from Aquarius says testing of Driggs’ sludge in years past revealed concentrations of metals, including aluminum, arsenic, chromium, copper, iron, magnesium, silver, and zinc, that may have inhibited bacterial growth, limiting ammonia consumption. Due to cost and difficulty, pretreatment for those metals likely would not have been possible or effective.

Still, he acknowledges, Aquarius could have done more: “If I’m being objective and honest, based on what our previous rep told us, Aquarius didn’t do a very good job of supporting the customer on a consistent basis.”

Several times over the years, the plant exceeded the discharge limits outlined in its permit. IPDES governs all point-source pollution, including wastewater plants, in an attempt to ensure that effluent meets standards set under the federal Clean Water Act. Allowed pollutant levels change based on the type of water source a plant discharges into; a larger stream or river can absorb and dilute higher levels than a smaller one. Driggs’ allowable discharge levels are low because the flow of the Woods Creek tributary is minimal; but, as Driggs Mayor August Christensen says, changing to a Teton River discharge point would have required a pipeline to be built, possibly an unacceptable idea for some in the community.

Permits regulate total suspended solids, coliform bacteria, phosphorus, and toxic metals, among other pollutants. For Teton Valley, the problem has always been ammonia. Decomposition of organic materials creates ammonia, a form of nitrogenous waste. Ammonia can be toxic to aquatic organisms, and nitrogen can feed algae, which cause blooms and other water quality problems.

Over the years, Jay and his team have tried many things to bring down ammonia levels. They’ve limited inflow and infiltration by decreasing the amount of groundwater allowed into the system, which helped with capacity issues. Yet no amount of tinkering has brought the plant into compliance.

“The best we could do was get it to work during summer months,” Jay says. “Then we stopped even getting some of the summer compliance.”

Noncompliance was not simply a nuisance. The EPA, which has the power to fine and sue towns that exceed permit levels, levied penalties over the years to spur action from the city. Finally, in 2020, town staff, the city council (August Christensen was a city council member then), and then-Mayor Hyrum Johnson started considering a full-scale replacement or expansion—something that would permanently fix the problem.

In October 2022, just before the city unveiled the idea, the EPA decided it had had enough.

Feeling Flush, or in the Hole?

Formal enforcement is probably not Troy Smith’s favorite part of his job. As the former wastewater compliance bureau chief for IDEQ, his department oversees permit holders and steps in when they don’t comply.

“Typically, we begin with what we call compliance assistance,” he says, meaning collaborative work to find and fix problems. If jurisdictions continue to violate permits, the department may send warning letters and notices, then issue formal violations that can include fines. Driggs went through the process over the years, to no avail.

The last step is bringing in the EPA, sort of like calling on your big brother to help you face that bully. The feds have oversight control over IDEQ and can call on the Department of Justice (DOJ) to sue cities over violations. “So they have come in and exercised that authority,” Troy says.

Federal litigation is often the final stick, a legal bludgeoning that encourages a permanent solution by slapping unaffordable fines on jurisdictions, then settling for a pittance and an assurance that the problem will be fixed. In Driggs’ case, the fines amounted to $160 million, a bankrupting sum that was reduced to $400,000 with the city’s promise to comply by 2029 after the plant’s remodel.

Plans for the original 2013 Aquarius system called for upgrades in 2030, roughly when the new system will come online.

“It was always the plan to be able to do an expansion and an upgrade,” Mayor Christensen says. “It just looks a little bit different now.”

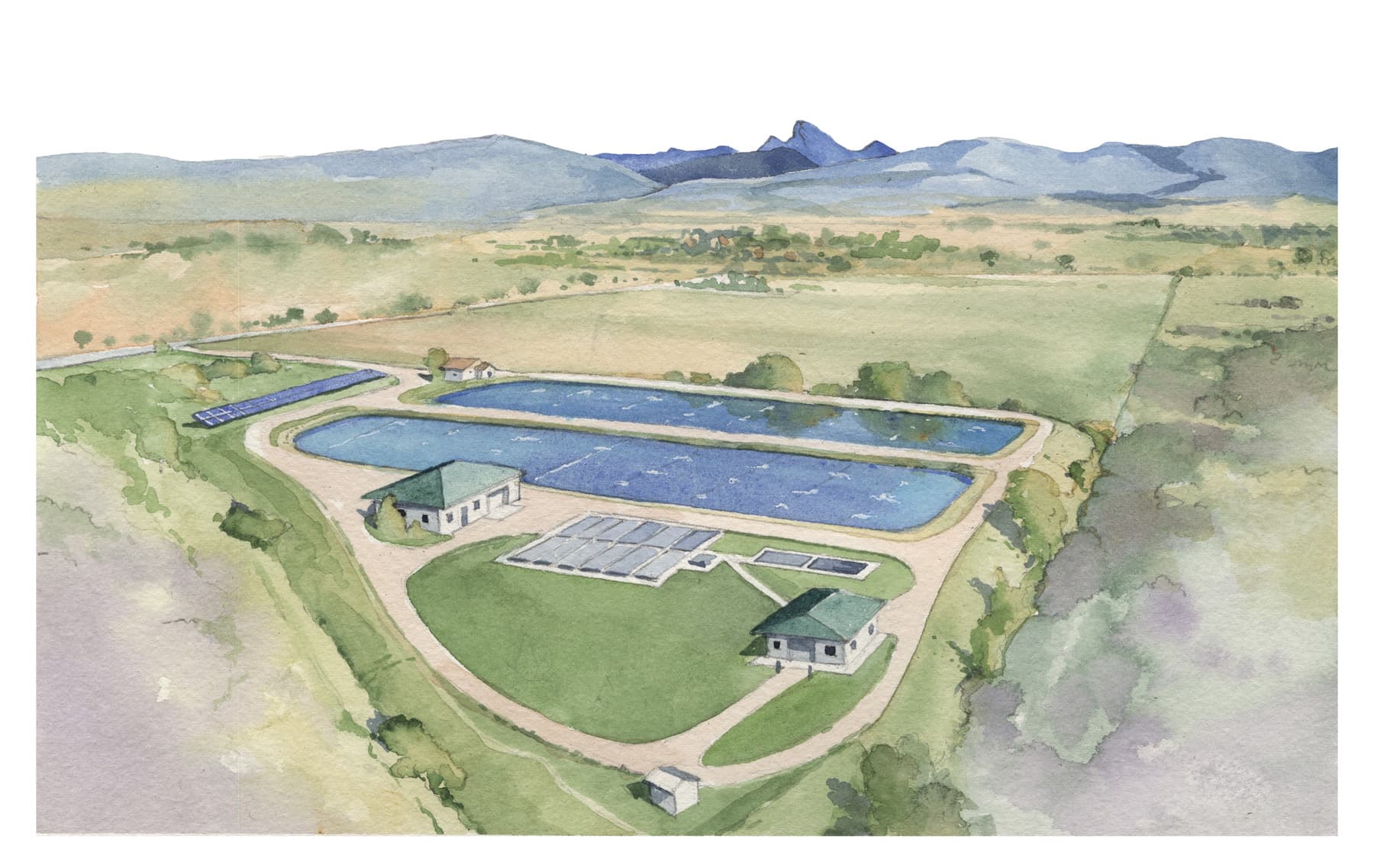

The city has chosen an activated sludge system, one of the most common wastewater treatment processes. In the new system, the steps are essentially the same—filter twice, treat, UV disinfect—but the actual treatment media will change. Much of the infrastructure, says Jay at Public Works, will be reused, including the initial filtering systems and the concrete basins.

Another important change should give the biology a better chance to eat all the ammonia. “It’s not a one-time pass; it gets recirculated,” Jay says. “So, in the current one, twenty-four hours, you’re done. One shot. Here, it just keeps getting recycled.” Giving the organisms more time means they’ll eat more ammonia and other pollutants, even when cold. If problems arise, Kubota, the company that produces the filter system the biological organisms will live in, offers a ten-year guarantee the plant will comply with its permits.

In March 2025, the City of Victor voted to pursue building their own independent wastewater treatment plant facility after their contract with Driggs ends in 2030. This change will alter the capacity and design of the Driggs project, but specifics are still unknown.

Construction is slated to wrap up in January 2029, and, under the consent decree signed with the DOJ, Driggs will need to show permit compliance for two years thereafter. By 2031, city officials could escape this ammonia-infused cloud. Between now and then, Mayor Christensen and her team will be tasked with educating the public and, more importantly, figuring out how to pay for it.

At City Council meetings and wastewater plant workshops, two questions continue to arise. First, why does the capacity of the new design cover only the next twenty years and account for just 4 percent annual population growth?

“In the infrastructure industry, like water and sewer, there’s the prediction of twenty years,” Jay says. “Once you get past twenty years, then you’re kind of guessing.”

And regarding population growth: U.S. Census data shows an annual growth rate of 3.74 percent from 2000 to 2023, right in line with the city’s projections for the next two decades. Factoring in a higher rate would lead to a bigger, more expensive plant, and if that projection turned out to be wrong, ratepayers would be left footing the bill. Funders also don’t like to back projects with a longer time horizon.

Speaking of costs, the other question citizens have asked is, “How much will my bill go up?” Unsatisfyingly, the answer right now is that city officials don’t know.

Initial estimates, which still included Victor, peg the cost to be around $25 million, but full design and financial plans aren’t due under the consent decree until January 2026. In Idaho, jurisdictions are allowed to pass along costs to ratepayers for infrastructure improvements, and utility users have already seen a 30 percent increase in charges in anticipation of construction costs.

As part of the consent decree, a judge has given Driggs the go-ahead to secure financing. That could include grants or low-interest loans from the state or the federal government. Several pots of money exist for these types of projects, and city staff will continue to apply annually for that revenue. Mayor Christensen says her last resort is a standard, high-interest bank loan, though that may be needed anyway to cover part of the total sum.

Costs of the loan would be passed along to ratepayers in the ensuing decades.

“We already have a utility bill that’s not low, and it will increase,” the mayor says. “But it’s very important for me to try

to have it at the most reasonable amount as possible.”

That answer may not satisfy everyone or answer all questions at this moment, but in less than four years Teton Valley will, hopefully, be discharging far less ammonia into that tributary of Woods Creek. By then, Mayor Christensen, Jay Mazalewski, and other city officials will be able to do something the rest of us take for granted—flush their toilets without worrying.