The Bridges of Teton (and Fremont) County

Until you see its two remarkable, gorge-spanning bridges, the Ashton-Tetonia Trail is slow to reveal its railroad-rich past.

Railroad ties, spikes, switch posts, abandoned railcars—evidence of the Teton Valley Branch from more than a century ago—seem strangely absent to the casual observer. The 29.6-mile-long pathway cuts a mostly straight line through open, rolling farmland and past grain elevators, small limestone outcrops, and abandoned farm machinery. Traveling along this quiet, sometimes weedy and bumpy track through valley farmland makes one wonder how it ever came to be in the first place. But when I arrived at the first and then the second of its major bridge trestles—built to over six-hundred-foot lengths and standing more than one-hundred-and-twenty-feet high—I realized this trail owes everything to its past.

Known as the Teton Valley Branch of the Oregon Short Line, owned and operated by the Union Pacific Railroad, the railroad freighted cargo—including cattle, limestone, coal, agricultural supplies, and basic provisions for Victor and Jackson residents—and passengers back and forth from Ashton to Victor (hence Victor’s motto as “The End of the Line”) once a day beginning in 1913.

“It was the only way from point A to B and opened up Teton Valley to the outside,” says Thornton Waite, railroad historian and an Idaho Falls resident. “Roads were bad, and it was just too expensive to bring stuff in any other way than by train.”

Abandoned in 1984, the Teton Valley Branch ended its days as a rail line. Its ties, rails, and various equipment were salvaged by 1994, but the bridges stayed put—historical landmarks from the railroad era, but too expensive to move. In 2010, after various upgrades to the pathway, such as newly installed bridge decking and railings, the Ashton-Tetonia Trail officially opened for recreational use.

On the fall equinox last September, I set out to link together—by bike—the Conant Creek and Bitch Creek bridges. In the town of Drummond, I headed north and soon reached the south side of the Conant Creek drainage, where the 672-foot-long trestle begins its horizontal span. It’s worth pausing here and pondering on why bridge aficionados love this engineering work of art. According to the National Registry of Historic Places, the Conant Creek Bridge is “possibly unique in the United States” due to its “innovative design” by the nationally known civil engineer, George Pegram. As chief engineer of the Union Pacific, the largest railroad company in the world at the time, Pegram patented his own truss design that saved on manufacturing costs by making the compression posts all the same length and provided more efficient assembling. Since he had the vertical space to do it at Conant Creek, he placed his trusses underneath the main deck, giving this bridge a curved, drapery-like effect. Equally remarkable is that parts of this bridge originally hung over the much-larger Snake River Bridge, built in 1894 in American Falls, Idaho. It was disassembled in 1911, and re-erected in 1911 and 1912 over Conant Creek.

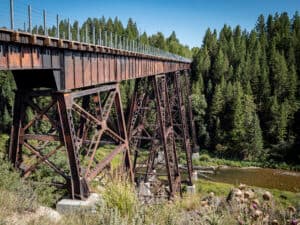

Built in 1924 to replace the original timber bridges, the Bitch Creek Bridge vaults 640 feet across a steep, densely treed gorge. Its standard deck girder design doesn’t earn the same rave reviews as Conant, but it’s breadth and position up high in the trees never fails to impress. The speed limit for trains on this route is rumored to have been twenty-five miles per hour overall, and twelve miles per hour over the bridges. I imagined a train conductor shouting “Hold on!” as he rounded the bend, applied the brakes, and tackled the exposed crossing of Bitch Creek.

I followed a group of horseback riders across and met Chuck Seligman of Victor, along with wife Annette and their dogs, who arrived there on bikes. “We just love it here,” Chuck said. “Railroad engineers really were perfectionists. There’s seemingly no uphill, no downhill.”

Ten years since its opening, the Ashton-Tetonia Trail continues to offer users a gravel-and-dirt adventure while also preserving some of the area’s forgotten railroad history. Managed by Harriman State Park, under the umbrella of Idaho Parks and Recreation, the rail-trail welcomes bikers, hikers, and horseback riders all year long, as well as snowmobile users during the winter months. You can ride the full nearly thirty-mile trail, follow the path to your favorite fishing hole, or simply hike in a few miles to see the colossal, century-old bridges. Either way, you are likely to find the place quiet enough to allow you to think back to a time of locomotives … and perhaps even detect the ghostly sound of a far-off steam whistle.