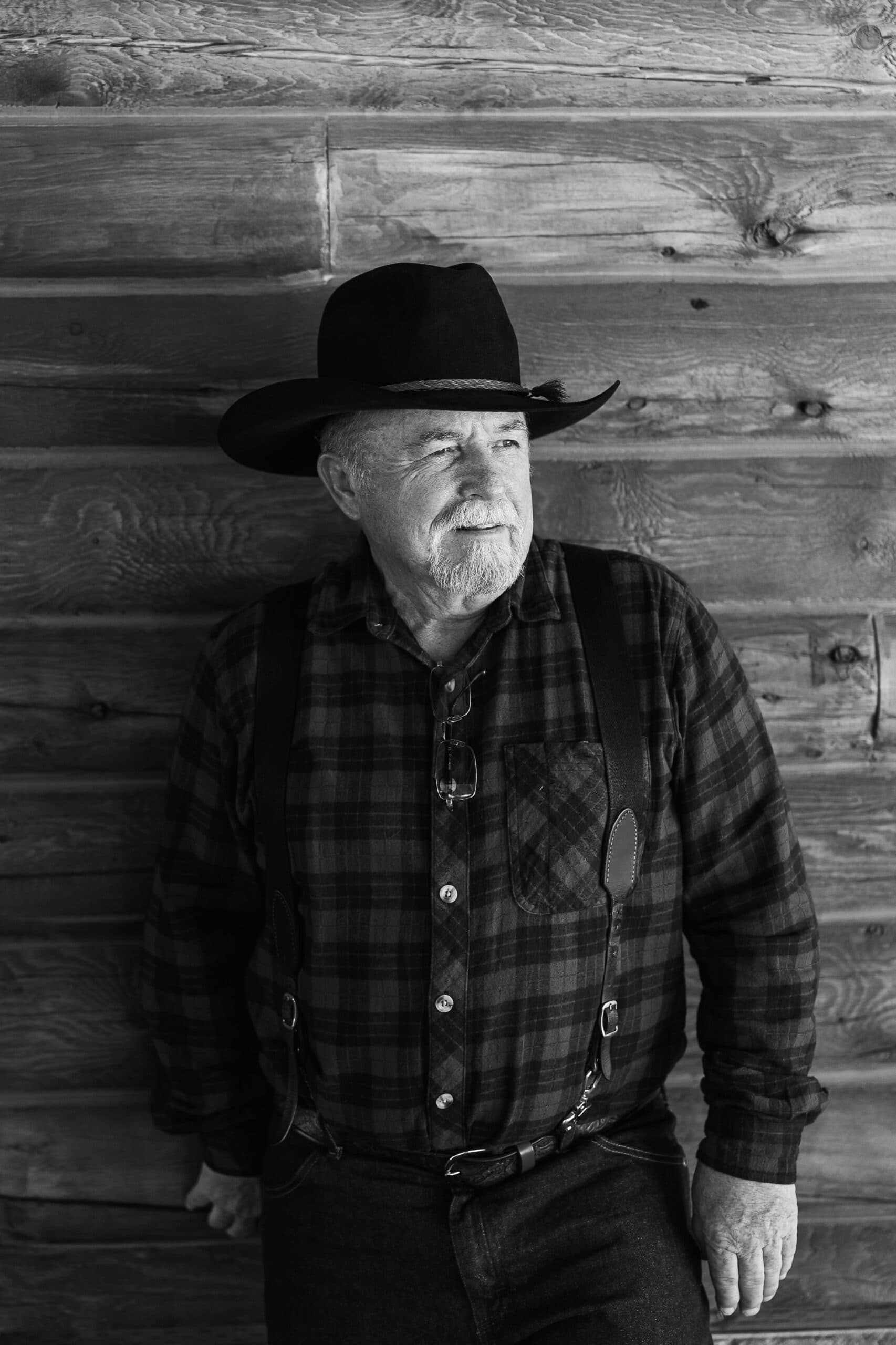

Rhyming the Cowboy Way

‘Word wrangler’ Bryce Angell tells it like it was … without the cuss words

Bryce Angell is not your classic Hollywood Cowboy. “I’m not one of those tall, lean cowboys in Wranglers that you see in movies,” he says.

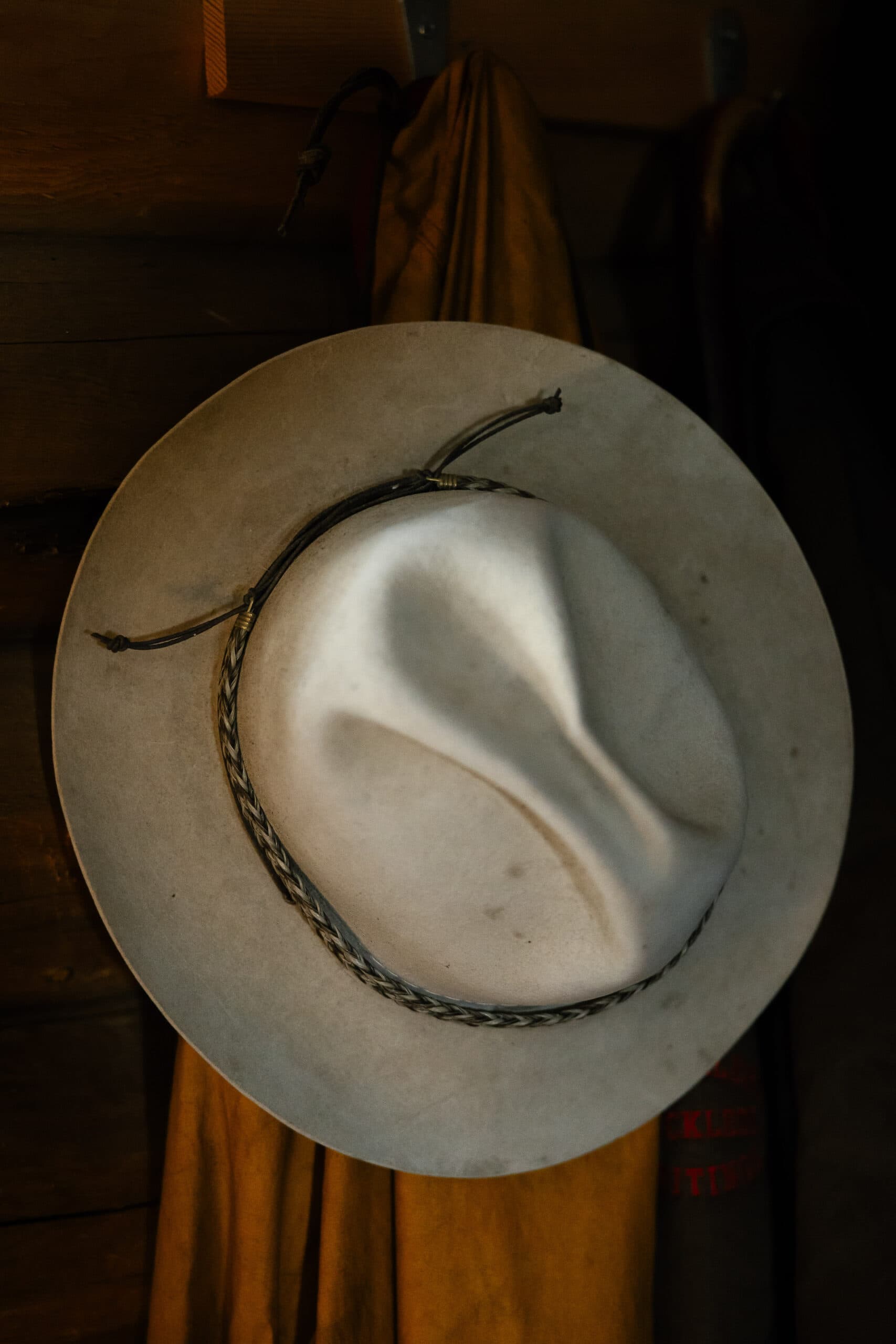

But despite not fitting into the stereotypical physical mold, Bryce, age seventy, has earned his cowboy bona fides. He grew up around horses—at times his family had as many as seventy-five head on their farm near St. Anthony—and he worked as a ranch hand for his father’s hunting and outfitting business in Island Park when he was a kid. When he was seventeen or eighteen, he says, he became a farrier. “I was already shoeing everyone’s horses in the neighborhood,” he says. “Horses were part of my work and part of my play, too.”

In fact, it was horses that brought him to cowboy poetry, and in this way, he may be more of a classic cowboy than he lets on. His first poem, entitled “Friends,” came to him while he was sitting around a fire on an overnight horseback trip in Utah in 2015. That’s the way cowboy poetry is said to have originated.

According to the Western Folklife Center, cowboy poetry started to emerge in the late 1800s, growing out of the western tradition of cowboys and cowgirls gathering around campfires along the trail to tell stories, sing songs, and fabricate tall tales. The poems helped create the romantic cowboy archetype—the image of a strong, silent, independent person, traditionally a man, who is bonded to his horse—that has become entrenched in the American psyche.

Cowboy poetry has grown more standardized over time. Today most is written in rhyming couplets with a rousing rhythm that lends itself to oral presentation. There is also an unspoken rule about subject matter. To be a cowboy poet, you have to write about ranch life. Robert Service’s poem, “The Cremation of Sam McGee,” shares a common structure with most cowboy poems, but because it is about gold miners in the far North, it falls outside the genre.

“Cowboy poetry has got to be country,” Bryce says. “All my stuff is country. If you have a horse or cow or some old timer involved, you have something to work with. Most of my poems are about things that happened to me growing up.”

One of his most popular poems is about branding cattle. He was a young kid and found himself becoming disturbed by the cattle’s constant lowing and obvious signs of distress. His cousin insisted the branding didn’t hurt the cows much, and convinced Bryce to feel what it was like by touching a piece of red-hot wire to his chest. Needless to say, that brand hurt Bryce a lot, but in keeping with tough-guy cowboy tradition, as he wrote in his poem, he managed not to cry. Today, that story is one his grandchildren love to hear over and over again.

After he wrote “Friends,” Bryce jumped into his newfound passion with both boots and began writing poetry every day. His wife, Terri, who is a schoolteacher, made sure he “crossed his t’s and dotted his i’s,” and in the process, became Bryce’s most reliable critic and editor. Soon he decided he wanted to share some of his work, so he began looking for places to publish. One of his first outlets was the Teton Valley News.

“At the time I had three newspapers printing my poems,” he says, “when a lady from Montana called and asked if I wanted to be part of a cowboy poetry group. I said yes, of course. But then I hung up and realized I hadn’t done anything like this before. I was sick about it.”

Bryce isn’t one to shy away from challenges, however. He’s a born storyteller and likes people, so he figured he might as well reach out to one of his heroes for guidance if he wanted to pursue his poetry dreams.

“I decided to email Baxter Black, the cowboy poet of cowboy poets,” he says. “I wrote, ‘Here’s my dilemma, you don’t know me from Adam, but if you have a minute, I’d appreciate your advice.’ Baxter got right back to me, and we ended up talking for over an hour. He gave me the best advice in the world.”

The key thing Bryce took from that conversation was not to swear in his poetry.

“Baxter said if you cuss in your poetry, you sound like you are trying to come across as a tough guy, but usually it has the opposite effect.”

Baxter also asked if Bryce had done any events before or shared his poetry. “Then he said, ‘You are already at the bottom so you have no where to go but up,’” Bryce recalls, laughing.

Baxter died in 2022, but Bryce still treasures his exchange with him. He was recently recounting the experience with his grandson, who was decidedly unimpressed, having never heard of Baxter Black. But his grandson is an avid soccer fan, so when Bryce compared Baxter to a favorite famous soccer player, his grandson understood. Baxter was a megastar.

Inspired by his late hero, Bryce’s poems are funny, self-deprecating, and full of insights into the little things in country life that result in humor, love, and wisdom. He writes about everyday experiences—with the country caveat—that his readers can relate to. With a lifetime spent around horses, he’s got plenty of material to work with, even though he sold his last one a year ago.

“I used to always have at least one horse or colt to work with,” Bryce says. “But I don’t do that anymore because of my age. These days, my hobby is writing. That keeps me busy.”

Bryce’s poems are in sixteen newspapers and five magazines, one as far away as Florida. Bryce retired from a career as a registered nurse at Eastern Idaho Regional Medical Center in 2019, though he continues to work eight hours a week at the Ashton Living Center. He lives on his father’s old outfitting base in Island Park in a house he and his wife built a few years ago. The couple have twenty-five grandchildren, so family and house projects keep them busy. Plus, every day Bryce searches his memories and writes a poem about his beloved country life.

“City life is different from country life,” Bryce says. “I think that’s why city people love cowboy poetry. It’s kind of romantic for them.”