A Good Prospect

“I wish you could see it like I can,” says Teton Valley native Dove Piquet, closing her eyes to envision Sam, a coal-mining community nearly the size of modern-day Victor once wedged into Horseshoe Canyon in the Big Hole mountains.

“But there’s absolutely nothing there now to tell you it was really a busy place.” Piquet, who died September 17, 2004, lived in the canyon in the early 1930s, working as an assistant to the boardinghouse cook. Back then, more than 250 miners and their families, if they had any, called Sam home. The town first boomed around 1912, and in the following two decades acquired its own post office, steam power plant, school, boardinghouse, sawmill and pool hall. Numbering nearly a dozen, the mines along what geologists call the Frontier formation supplied “Idaho coal for Idaho people” via an Oregon Short Line (OSL) spur from Tetonia.

But the fickle nature of the coal veins blackened Sam’s prospects, and when hope and assets finally dried up in the Great Depression, there wasn’t anything else to keep people in the canyon, 12 miles due west of Driggs. The town’s quick demise is perhaps more intriguing than its establishment. Today, even the cemetery is hard to find, says Bates resident Francis Ripplinger, whose family was among the last to mine in the canyon.

“They say there’s millions of tons of coal in there,” he explains, citing a handful of Idaho and U

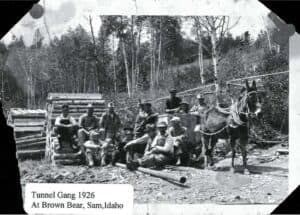

nited States geological surveys, “but the mountains beat us.” Like any other living to be made in turn-of-the-20th-century Teton Valley, mining was a rocky prospect. All the work was done by men, not machinery: most shafts utilized push-carts for the transport of coal to the mine’s mouth. To the end, Sam ran on steam rather than grid electricity (even after most of the valley floor was powered up in the 1920s). Henry Flamm, who was first to mine the area, sank two shafts along Horseshoe Creek as early as 1882, but the 30-inch veins proved unprofitable. As other mines were established, including William Hillman’s Horseshoe Mine (1901) and Brown Bear Mine (1904), and the Rammells’ Packsaddle Mine (1906), it became clear that the coal beds were as rumpled by the region’s geologic activity as was the visible topography.

“They’d be working along the vein, and then it would disappear,” Ripplinger says. “They’d have to follow their hunches to find it again, maybe five feet over this way, or three feet over that way.” Veins ranged from a few inches wide to 10 feet across. In many places, independently owned mines tapped the same vein, just at different points. “Prospectors would watch the ants,” Ripplinger explains. If they carried coal dust, a dig was set. The telltale debris became known as “bug dust.”

One by one, enterprising mine contractors dug into the beds to chisel out a profit. Lump coal, which came out in chunks, brought a higher price, sometimes as much as $14 per ton, with delivery to the valley floor and beyond. Slack or minerun coal, which was shattered nearly to dust, brought $11 per ton in 1950, just before the last families gave up part-time mining operations. United States Geological Survey assessments of the coal’s content indicated that it was as good as any coming out of Utah or Wyoming.

Most mining was done by the roomand-pillar method, Ripplinger explains. Miners would blast the end of the respective mine’s tunnel with dynamite, then frame up the gained distance of seven to nine feet with timbers hauled in by mule or men. Then they’d blast out a “room” 20 to 40 feet high above the tunnel, staying within the width of the vein, which ascended at such an angle that the miners were always leaning, Ripplinger says.

The fragmented coal would fall down the makeshift chute into a coal car positioned in the tunnel. “Some people got greedy and put their rooms too close together,” Ripplinger says. “Then [the tunnels] were in danger of caving in—and some did.”

Water was another problem. “The shafts would go down a distance, then almost level off, with a slight incline from the bottom as they went farther in,” Ripplinger says. Water would drain to the elbow in the shaft and would have to be periodically removed by skip or primitive pump.

Despite the danger, miners had few accidents. “People really worked as though their lives depended on it,” the late Bob Smellie of Tetonia, a former miner, explained in a May 2004 interview.

“They were pretty careful.” The only death, reported in the Teton Valley News, was that of 23-year-old Eugene Eddington of Driggs, who was killed by falling rock.

By 1917, three promising coal beds had been identified: the Brown Bear, the Progressive and the Blacksmith. The Brown Bear Mine, located on its namesake bed, proved the most reliable and found its way to the center of attention. Having changed hands twice, it became the site of a crosscut tunnel that would eventually reach more than a mile into the mountain. Its owner at the time, R.S. Talbot, christened the growing settlement “Talbot” after himself and organized the Idaho Coal Mines Company.

“The tunnel intersected the other mines along the beds in the [canyon] drainages,” Ripplinger explains. “As soon as it hit the original Hillman workings, air flowed through it. Other mines that didn’t have circulation had to have big fans to bring in fresh air.”

Workers heading into the mines for the day could get a sack lunch at Sam’s boarding house. Piquet, then a teenager, helped the cook (or cooks, as staff turnover was frequent) make meat sandwiches, and cookies for dessert.

“Pretty soon we got onto who had sugar in their coffee and who had cream,” she says with a chuckle.

Some of the bachelor miners would linger in the boardinghouse in their spare time, Piquet remembers. “Once, two guys who had been hurt in a mining accident got in the habit of playing cards with the cook, after lunch when she had a few hours,” she says. One foreign miner had a crush on the cook and got jealous when the other worker played cards with her, Piquet explains. “He saw them [playing cards without him] and left; I’ll never forget the look on his face. When he came back, he had a long knife under his coat, and he just jumped at the guy. The cook grabbed her broom and started swatting him, and I ran out to get Mrs. [Edna] Mikesell, who was in charge.

They got it sorted out, but what if he had killed that guy right in front of me?”

Life in Sam wasn’t always so exotic, though, because locals, mostly members of the LDS Church, made up at least a third of the workforce and influenced the town’s piety. “Some of the mines hired in professional [Russian and European] immigrant miners because they could work faster than the average farmer,” Ripplinger says, “but with the work being on-again, offagain, it was easier to hire whoever was available in the valley.” Kids attended school taught by Edna Mikesell (who also distributed the mail), and the community, often called “camp” in the Teton Valley News of the day, hosted valley fiddlers and accordion players for dances on the schoolhouse’s smooth wood floor. For Christmas in 1925, Santa came to a celebration at the schoolhouse bearing gifts, candies and oranges. The fur on his costume caught fire, singeing his nose and neck, according to the Teton Valley News.

In 1918, Talbot and the Idaho Coal Mines Company secured the railroad spur from Tetonia, at a cost of $350,298.82. (The company put up $64,890.60, according to a 1951 survey by Thor H. Kiilsgaard.) Talbot agreed to maintain the track, an expensive proposition given the valley’s winters. The OSL dropped off cars, then picked them up when they were full. Disputes erupted almost immediately. Mine operators contended that intermittent service hampered productivity. The OSL argued that the unreliable production volume didn’t warrant the expense of transit.

During storms, Sam residents had to wait for the snowplow to come through, which would sometimes blow shut the wagon road below, cutting off local access. Today the road runs along the abandoned rail bed.

Regardless of who invested in the mines (at one time, Idaho state mine inspector Robert Bell even drove his own “Bell Cut” shaft), supply never met demand—or speculation. The Brown Bear Mine, for example, changed ownership three times, eventually landing in the hands ofHenry Floyd Samuels, a zincmining magnate from northern Idaho.

The holdings of the newly renamed Teton Coal Company, including the main coalloading tipple, power plant, mill, equipment and a number of buildings in town, cost $508,474. Samuels gave the town its current name and built one of its largest houses, a four-room cabin.

As owner, Samuels’s biggest concern was his operation’s relationship with the OSL. The value-to-service equation finally went before the Idaho State Utilities Commission in 1924. At the time, the whole valley seemed dependent on the success of the mines. Minute-byminute coverage ran long and large in the Teton Valley News, and residents turned out in their Sunday best at public hearings before the commission. Businesses in Tetonia, Driggs and Victor put coal samples on display to emphasize their support of the coal-driven economy. And in that round, the mines won out.

By the time the Depression hit, however, Samuels had unsuccessfully invested much of his personal fortune and refinanced several times, calling on personal friends. Despite thrifty management by Henry Mikesell (Edna’s husband), a well-liked general foreman, the Brown Bear Mine and other subordinate operations disappointed investors— including the Oregon Short Line. In 1933, at the order of the Interstate Commerce Commission, Sam lost its rail service.

The tracks remained into the 1940s, when they were torn up for use as scrap metal in World War II efforts. Without rail transit, most mining operations folded, though some residents, including the Mikesells and even Samuels himself, stayed on to work the smaller man-powered mines. Then in the spring of 1935, the main coal-loading tipple burned down, probably a casualty of carelessness with cigarettes. With operations reduced to their humble origins, coal distribution was limited to the valley. Valley farmers, like Martin Piquet (Dove’s husband), made money in the winter by hauling wagonloads of coal to Driggs for domestic use. “He’d leave at 6 [a.m.] to drive his team to the canyon, then wait for the wagon to be loaded,” Dove says. “By the time he drove it to Driggs and drove home, it was 9 [p.m.]”

Valley businesses and residents could burn coal or wood in a good stove, Ripplinger explains. The resource was especially important when winters were harsh and wood stores dwindled. Families, including Ripplinger’s, worked the mines intermittently until the tunnels became unsound in the 1950s. Samuels sold his holdings to R. H. Russell of Spokane in 1946, for $55,000. Many of the mines’ mineral rights remain private.

Today Sam contains nothing but a few depressions that indicate residents’ root cellars and the collapsed shafts of mines, but the town’s spirit lives on in the 4,623,650 tons of coal that still lie in the hills (according to the 1951 Kiilsgaard survey). The glint of untapped fuel development, including that of oil, lies just beneath the valley’s identity as a potato-growing region turned resort community. At this point in history, one natural resource (pristine and dramatic topography) trumps another (fuel exploration).

“When I was a kid, we would go looking for mud holes in the canyon,” Ripplinger says. “We could stir them up and light a match over them, and the gas would burn.”