From Railhead to Trailhead

Transportation, in its various forms, is a vital cog in the wheel of local economies, and much history of the West can be told through the tales of moving people and goods. It was often on the trail of transport that residents made their livings, providing services in this region to well-heeled tourists who flocked to destinations like the national parks.

Francis Cloward Gillette was one such person, spending most of his career in transportation-related businesses. Coming into the world on the first day of 1901 in Teton City, Idaho, “Fran” grew up alongside the automobile: The legendary Model A, the Ford Motor Company’s first car, began production in 1903. The ultra-popular Model T first left the factory in September 1908, when Fran was going on eight; in production for almost twenty years, the “Tin Lizzie” is widely considered the first affordable automobile, the personal vehicle that opened up independent travel to middle-class Americans.

Despite the popularity of it and other motor vehicles, only horse-drawn conveyances were allowed in Yellowstone National Park until 1915. On July 31st of that year, a Model T became the first auto to legally roll into the park. (Ironically, just two years later, horse-drawn vehicles were banned in Yellowstone.) It was at about this time that Fran went to work as a clerk for his father, who managed a mercantile in Teton City. In the spring of 1921 the family relocated to Victor, where Fran continued working for his father at the Victor Mercantile Company. He never did finish high school, but his on-the-job training of working with the public provided an invaluable education for his future pursuits.

About three years later, following a year-long stint pounding nails in California, Fran returned to Victor and went into the pool hall business. He struck up a friendship with William J. Hynes, the Union Pacific Railroad agent in Victor. This evolved into a business partnership when the two purchased a Model T for hauling freight from Victor over Teton Pass to Jackson and Moran. Fran’s work in transportation began to roll.

By 1927, Fran—at just twenty-six years old—and his partner had a trucking business that was thriving and growing. To house and make repairs on their fleet, they purchased a Main Street garage in Victor from George Woolstenhulme, whose daughter Ora would marry Fran the following year. Fran soon diversified and went into the wholesale gasoline and oil business, working first as an agent for the Standard Oil Company of California and later for the Utah Oil Refining Company. He also had a bulk plant in Jackson that he operated in partnership with his brother, Wendell. Finally, Fran acquired a Ford Motor Company franchise and another large garage, and now had an impressive triad of transportation-related businesses: a gasoline and oil distributorship, a freighting company, and a car dealership.

The fledgling Grand Teton National Park, protecting the high peaks and southerly piedmont lakes, was established in 1929. Private owners retained most of the valley below—which, in an oft-told tale, John D. Rockefeller Jr., under the guise of the Snake River Land Company, began buying up, with the intent of adding huge acreages to the national park. And this he ultimately did. In 1943 much of the valley was set aside as the Jackson Hole Monument, which was incorporated into the national park in 1950.

The creation of Grand Teton National Park fueled yet another Gillette enterprise. Among the properties purchased by the Snake River Land Company was the original Moran town site, or “Old Moran,” located at the outlet of Jackson Lake Dam. Geographically, Old Moran was the ideal stopover for tourists who had seen the wonders of Yellowstone and were en route to catch the Union Pacific Railroad’s Teton Valley Branch in Victor [see preceding story, “The First and Next 100 Years”]. Rockefeller was not interested in funding tourist operations— he essentially wanted to erase evidence of human occupation and restore the park’s natural beauty. So, in 1930, in the spirit of free enterprise, a group of Idaho-based businessmen joined forces to create the Teton Investment, Lodge, and Transportation Companies, soon making accommodations available at their Teton Lodge and the [original] Jackson Lake Lodge in Old Moran.

The transportation company bused passengers between Moran and Victor, where they would board and/or disembark the train. According to a life story penned by Fran, he “became acquainted with the early management of the Teton Lodge Company and acquired service stations at Moran, Jenny Lake, and at the junction … north of Moran on the road to Yellowstone Park.”

Mary McKinney, in her book The View that Inspired a Vision: The History of the Grand Teton Lodge Company and the Rockefeller Involvement, writes that visitors sometimes boarded the wrong train car in Salt Lake City, thinking they were headed for West Yellowstone, Montana, but finding themselves instead at the end of the line in Victor. Of those who decided to visit Jackson Hole from there rather than backtrack to Ashton, some caught a ride with Fran on his fuel delivery truck over Teton Pass to Jackson or Moran.

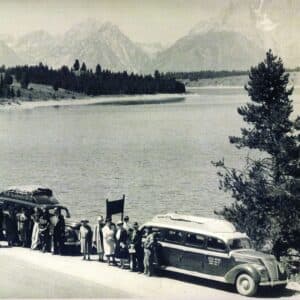

America’s national parks were becoming ever more popular. Although visitors could drive personal automobiles in Yellowstone by 1915—and in Grand Teton National Park since its inception—a lot of people still came to the region by rail. The demand to transport visitors to and from railroad termini near the national parks grew.“The Lodge Company requested that I take over [their bus] operation, which I did in 1935,” Fran wrote. The company leased its transport concession to Fran to run as an independent subcontractor. The first public transit vehicle he used was a Ford station wagon, “which adequately took care of the number of passengers in 1935, but [that number] grew each year.” When the capacity became inadequate, he bought “stretch outs,” very long Ford station wagons that had been cut in half and had two rows of seats added. In 1941 he graduated to a twenty-one-passenger Flxible bus (the Flexible Side Car Company changed its legal name to “Flxible” in 1919 for trademark purposes). Later, when visitation really picked up after World War II, Fran purchased two larger buses that carried about thirty-seven people each. Eventually, he and his employees drove a pair of forty-five-passenger 1957 Crown buses between Moran and Victor.

From the beginning, because of her responsibilities at home—including the raising of five children—Ora hadn’t the time to participate in her husband’s business endeavors. As the years passed, however, two of their offspring drove for the Teton Transportation Company. In his memoir, Fran wrote, “My daughter Donna began driving one of the station wagons for me in her teenage years, and my son Jerry drove the small Flexible [sic] bus over Teton Pass like a veteran driver when he was a teenager. This was a tremendous responsibility for a boy so young.” Jerry also worked at his dad’s service station in Moran, and daughter Barbara worked as a waitress in Old Moran, riding in one of her dad’s buses to get to work.

“We had some wonderful drivers that drove those buses over the Teton pass to Jackson,” Fran wrote; “through Grand Teton National Park and finally to Moran. [There] we traded passengers with Yellowstone Park [buses] and then drove back the same way, arriving in Victor in time to have supper at the Timberline Café and board the Union Pacific Railroad train for the trip to their destination.”

Perhaps the most wonderful driver of all was Stanley M. Boyle, who met with Fran in 1935 to talk about buying a car. But rather than selling Stan his own wheels, Fran offered him a job driving one of his station wagons transporting tourists. Stan was the high school principal in Victor and needed a summer job, so he accepted and moved his wife and two daughters into a small cabin at Moran. Stan drove the road between Moran and Victor twice daily. He loved history—he majored in the subject in college—so he began giving historical lectures as he drove along. Tourists enjoyed these narrations and considered them a bonus to their western adventure.

Fran encouraged Stan to continue his interpretive tours, and even sent new drivers to train under him so they too could learn the history. As time passed and more people booked guided tours, microphones and loud speakers were added to company vehicles. According to Stan’s son, Stanley S. Boyle, the bus trip was his dad’s life. Stan worked for Teton Transportation continuously for more than forty summers, except for 1942–1944, when park visitation plummeted during World War II.

Fran remembered other regular drivers who were assets to his bus business, as well: Floyd Stratton, John Gunner, Bryan Wahlquist, and Russell Stone, Fran’s “right hand when it came to keeping the buses in top condition.” Other drivers hauled passengers for only a summer or two.

As mentioned previously, John D. Rockefeller Jr. initially had no interest in creating tourist services. But soon, understanding that he was largely responsible for the hordes of people now pouring into the park, he apparently felt obligated to do it. “I suppose I ought to build a hotel,” he reputedly said, and started planning it.

At about the same time, the Interstate Commerce Commission ruled that franchise holders, such as Rockefeller’s Grand Teton Lodge Company, had to operate their transportation lines directly and not under subcontractors like Fran. Rockefeller approached Fran in 1955, offering to purchase his transportation company, which the wealthy industrialist wanted to operate from his newly constructed Jackson Lake Lodge north of Moran.

With some reluctance—knowing he couldn’t compete with Rockefeller’s company otherwise—Fran sold his successful Teton Transportation Company. But he stayed on as the superintendent of transportation for the Grand Teton Lodge Company.

“I was still in charge of everything having to do with the maintenance of the buses,” Fran wrote, “[and with] storing them for the off season, hiring the drivers, scheduling the tours and meeting the Union Pacific train in Victor & Yellowstone Park buses at the lodge. It was a big job and a lot of responsibility, especially when I was required to be at the lodge in the office they provided, so I was away from my family for four months out of the year.”

Fran retired at the end of the 1959 season, deciding it was “time to … spend some time doing other things. I had worked in the tourism business for twenty-four years and loved being in it. … Russell Stone was hired to take my place as the transportation manager for the Lodge Company.”

For a quarter century, Fran and his drivers provided visitors a crucial link between the train platform and their national park destinations—during the early boom years of visitation to those parks.