Beaver Dick Leigh

“An important fellow in these here-a-bouts”

The massive cottonwood trees lining the Teton River canyon bottom appeared stark and lifeless; the canyon edge above was blanketed with drifted snow.

Bundled in winter garb, some forty or fifty people had arrived on bobsleds and solemnly assembled near the canyon’s rim. The large gathering was for Richard “Beaver Dick” Leigh’s funeral.

The March 1899 graveside service, located north of today’s Newdale, Idaho, overlooked what had been Dick’s 160-acre homestead; on the eastern horizon, the Teton peaks presided. And, as Dick himself had once written, “… it was a grand sight.” A neighbor’s words summed it up: “Beaver Dick was quite an important fellow in these here-a-bouts.”

Literate for the time and place, Dick had literally penned his own obituary in a missive to a friend: “I am the son of Richard Leigh formerly of the British Navy and grandson of James Leigh formerly Colonel of the 16 lancers, England. I was born Jan. 9, 1831 in the city of Manchester, England. Came with my sister to Philadelphia, U.S.A. Went for the Mexican War at close of ’49 … then came to the Rocky Mountains and here I die.”

An old English name, Leigh means “a clearing in the forest.” Frontiersman, trapper, miner, Army scout, ferry operator, government expedition and hunting guide, early settler, and diarist, his was a well-known and respected name in the Greater Yellowstone region in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Guided by Jim Bridger in 1860, the U.S. Army Raynolds Expedition conducted the first organized exploration of the Yellowstone region’s vast wilderness. They were undoubtedly surprised to encounter Dick, a solitary, buckskin-clad Englishman with a Cockney accent, encamped in Pierre’s Hole (Teton Valley). Dick had been trapping in Teton Valley as early as the mid-1850s.

Dick’s features made him readily recognizable: thick red hair, heavily bearded, freckled, blue eyes, pockmarked face with a rather large nose. Among the Indians, he was known as “Ingapumba,” the red head; others called him “Beaver Dick,” for his prominent front teeth.

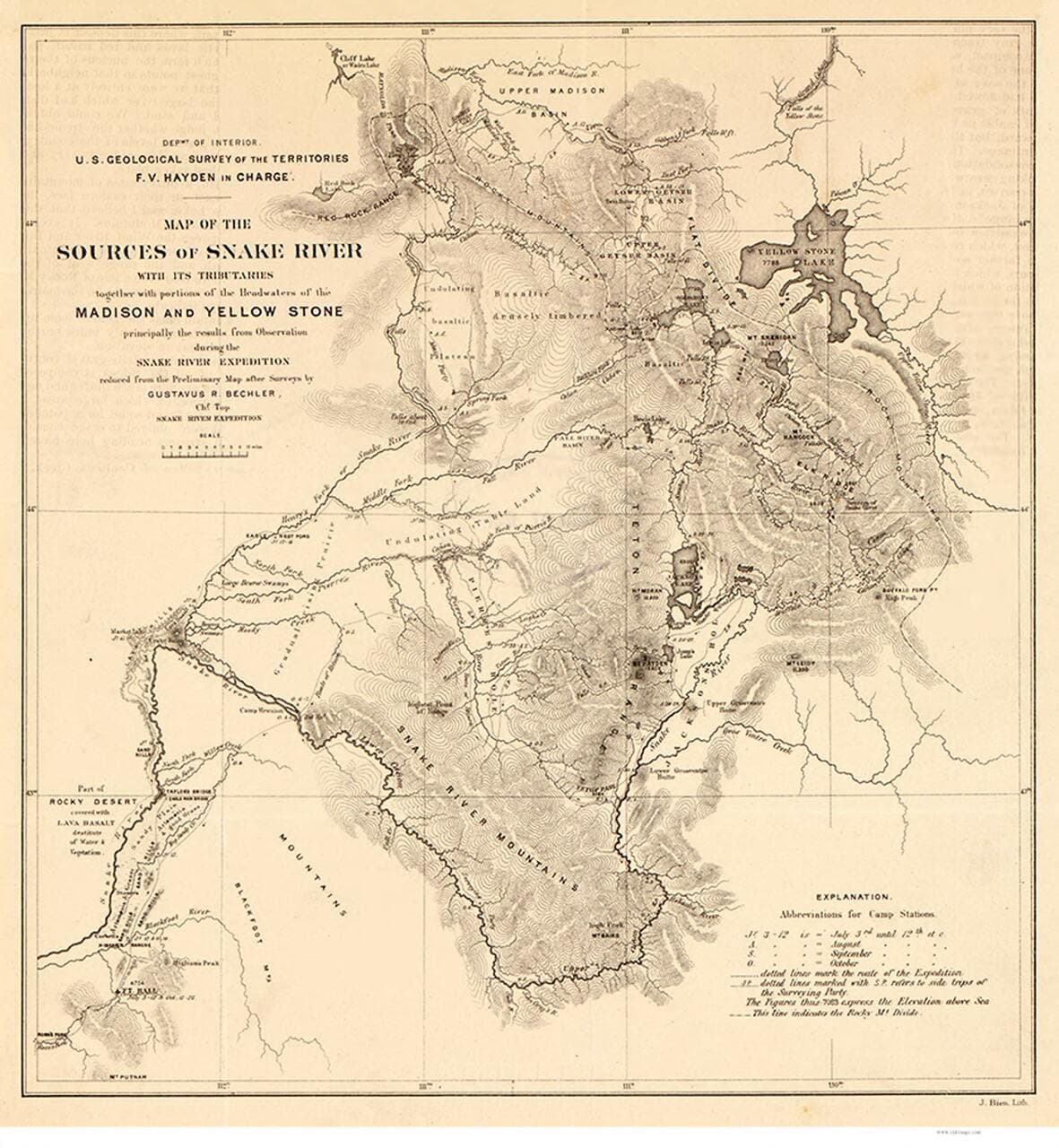

Dick guided the 1872 Hayden Expedition responsible for surveying the natural features that led to the establishment of Yellowstone National Park. Nathaniel Langford, a principal member of the survey party and, later, Yellowstone’s first superintendent, endorsed Dick: “…there is not a stream, lake, or range in any direction from us, for hundreds of miles, with which he is not familiar. He has the entire mountain region in his mind’s eye, like a map.”

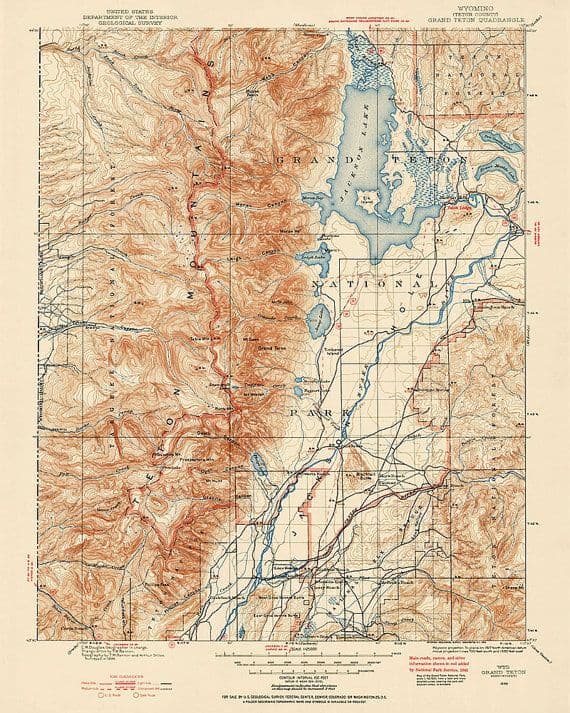

Today, in the Tetons, Leigh Canyon, Leigh Meadows, North and South Leigh Creeks, and Leigh Lake are named after him. Hayden Survey members immortalized Dick’s Shoshoni first wife by naming the singular lake at the mouth of Cascade Canyon after her: Jenny Lake.

In the cold darkness of winter in 1876, in their one room cabin alongside the Henry’s Fork, not far downstream from the Teton River confluence, Dick suffered a horrific tragedy: Jenny and their six children contracted smallpox. His entire family died within twelve days. Dick, though seriously sickened himself, survived. Dick’s great-grandson from his second family and his wife related the ghastly tale in Beaver Dick: The Honor and the Heartbreak (Yelm Mountain Publications, 1982): “…assisted by trapping comrades, Dick buried his entire family in the cold frozen earth.”

As the Jenny Leigh memorial explains today, because the ground was frozen, they buried the entire family “under the [unfrozen] cabin floor.” After that, Dick burned the cabin and its contents to prevent spread of the disease.

Weakened, Dick complained of health issues, injuries, and loneliness; the heartbreaking disconsolate loneliness that deep grief imparts. “… I am so lonesome no matter how tyard [sic] I am.”

Flashback to a bitter cold winter night in 1862: While returning from Fort Hall, Dick stopped at a Bannock Tribe couple’s encampment. The woman, in the throes of childbirth, was the sister of Chief Targhee. Dick assumed the role of midwife and helped deliver a tiny girl, who was given the name Susan “Sue” Tadpole. The grateful father, Pam-Pig-E-Mena, known to settlers as Bannock John (he reportedly had massive scars from a grizzly bear mauling), promised the tiny infant to Dick to be his wife when she became of marriageable age.

In one of those stranger-than-fiction stories that have come out of the American West, in the spring of 1879, more than two years after the deaths of Beaver Dick’s wife and children, he married Sue Tadpole, now sixteen. Dick was three times her age.

Dick and Sue had three children—Emma, William (“Bill”), and Rose. Dick continued his seasonal routine accompanied by his new family. They traveled across the northern end of the Teton Range by way of the Conant Trail, camping at Jackson’s Meadows (features named by Dick); they hunted, trapped, and camped throughout today’s Teton Wilderness; driving their horse herd with them, the children rode burros.

In late autumn 1892, the Leighs wintered along the lower Teton River, a few miles north of his earlier Henry’s Fork cabin site. Beneath the river canyon rims, below 5,000 feet in elevation and among the sheltering cottonwood groves, the setting was relatively mild, with a concentration of wintering big game animals.

By 1887, large numbers of Latter-day Saint settlers had ascended into Pierre’s Hole. Although not a church member himself, Dick found himself in a key advisory and emissary role among the Latter-day Saints. Teton Basin underwent rapid change. The nearest settlement from Dick’s homestead, only three miles away, was Wilford, Idaho; by 1887 it boasted a post office and school. Dick became a school trustee. Writing in his journal, he reflected: “I ave [sic] the pleashur of knowing that I ave led the settlements of the snake river…”

Dick proved up on his squatter’s claim along the lower Teton River. Government Land Office Records show his homestead patent (No. 1799) was granted by President Glover Cleveland on July 8, 1895. His home consisted of two log houses connected by a breezeway. The family had a large number of buckskin horses, a milk cow (supposedly the first cow brought into the area), and a garden. They cut and stacked wild hay. At times, a good number of Bannock Indians, to whom Dick was related by marriage, would visit and camp within the cottonwood groves on his river bottom property.

By the late 1890s, although he continued guiding hunters, Dick had begun to suffer from poor health. Fremont County records show he sold 120 acres of his homestead in June 1898 to William A. Hague, a hunting acquaintance.

After Dick’s passing, Sue lost the remaining forty acres of their homestead in lieu of payment of taxes. She eventually moved to the Fort Hall Reservation, where she and two of her children are buried in the Episcopal Mission Cemetery. As she was dying, it is said, Sue wept because she was unable to be buried next to her husband along the Teton River.

Beaver Dick Park

Created in 1964 to memorialize Dick Leigh, the park is located seven miles west of Rexburg, next to the Henry’s Fork Bridge crossing on State Highway 33. Camping, picnicking, and interpretive facilities are provided. People frequently assume Dick is buried there, but he is not.

Episcopal Mission Cemetery, Fort Hall, Idaho

Sue, and daughters Emma and Rose, are buried in monumented graves at the Episcopal Mission Cemetery at Fort Hall, Idaho. There is also a memorial at the Fort Hall cemetery for Susan Leigh’s parents, Bannock John and his wife Tadpole, gravesites unknown. Dick’s son, William, at the outbreak of World War I, traveled to Shelby, Montana, to become a pilot. While there he died from influenza and was buried in an unknown location.

The Jenny Leigh Pioneer Cemetery

The site of the tragic deaths of Jenny Leigh and her six children on the bank of the Henry’s Fork is memorialized and poignantly interpreted. Located six miles west of Rexburg off State Highway 33, it is on BYU-Idaho Livestock Center grounds. BYU does not allow general public access to the site, but self-guided or small group tours can be arranged. The site and signage are maintained by the Rexburg Chapter of the Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Living Descendants

Descendants of Beaver Dick, through his daughter Emma’s marriage to Kit Carson Thompson, still reside in the St. Anthony, Newdale, and Teton, Idaho, areas.

Teton Dam

Except for the general topography, the landscape Leigh knew 120 years ago is unrecognizable today. Overseen by the Bureau of Reclamation and promoted by politicians, who ignored environmental objections, the construction of Teton Dam, a 305-foot high earthen structure, was completed in 1976. It was located only a few miles upstream from what was Beaver Dick’s homestead location. Catastrophic failure of the dam occurred shortly after it filled. Along with loss of life, the calamitous downstream damages were calculated at two billion dollars. In the canyon where Beaver Dick’s homestead and cabin had been located, the debris-filled flood water deposited coarse sand and gravel, scouring the channel and canyon walls, and destroying the original cottonwood gallery forest. His grave on the rim within farm fields was not impacted; but downstream, the Jenny Leigh cemetery site was severely flooded, requiring it to be completely restored. The town of Wilford was wiped from the map.