A Skiing Heritage

Valley Pioneers Leave A Legacy Of Winter Fun

Holmes, who still lives on Victor’s Main Street and remembers those days with crystal clarity, says some thought Teton Valley was too prim and proper for the Count, that Sun Valley was chosen because of its less restrictive attitudes regarding social drinking. But Homes believes Sun Valley won out because of its natural thermal springs and less thickly forested topography, which made it easier to sling cables and catwalks across its bare hills.

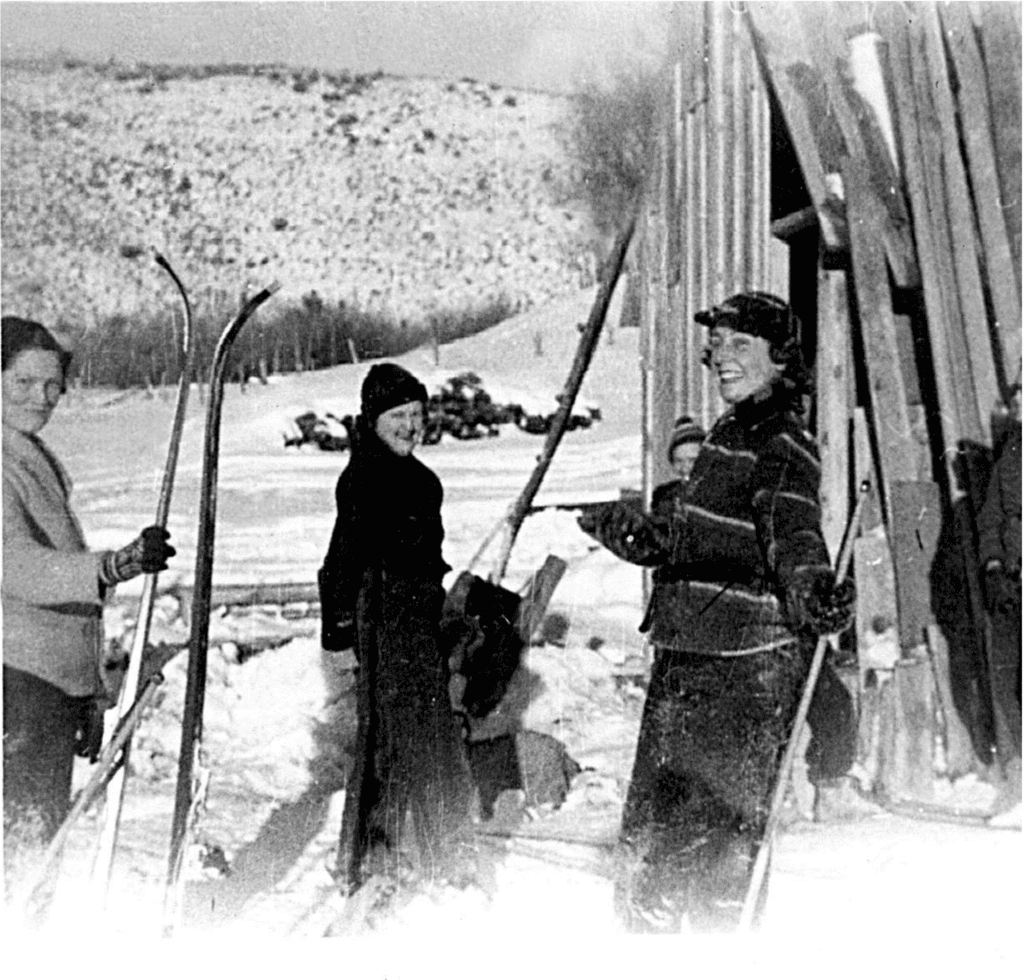

Still, even without the railroads’ financial backing, Teton Valley residents wanted a community ski hill and with the aid of $5,000 in Works Progress Administration (WPA) funds, a protected slope about one mile southeast of Victor in the Allen Creek drainage was cleared during the Depression-era winter of 1936-37. The outline of the ski run is still clearly visible today.

“We wanted a ski hill,” Holmes says, “and so we got together and did it. We did it for economic reasons and recreational reasons.” The hill was cleared during the winter, so the men actually had to shovel snow away from the base of the trees before they could be felled. Holmes, who ran the

drugstore in Victor, helped direct the ski hill project as a volunteer. About ten area farmers who needed winter income provided the manual labor, which was compensated with the WPA funds. The U.S. Forest Service donated a log cabin formerly used by the Civilian Conservation Corps in Mike Harris flat, for use as a warming hut. “We had to take it apart and bring it back here and put it back together,” Holmes explains. The hill itself was on public land, with the level property at the bottom privately owned by James Ingram. “Jim let us put the cabin there and we gave him payment from the food in exchange, “Homes says.

The run, also referred to as the Victor Ski Slide, was three quarters of a mile long and 300 feet wide, with a vertical drop of 782 feet and a grade of 17 to 22 percent. “Expert skiers consider the hill and ski run one of the best in the country,” Gesas told the Teton Valley News shortly before

the ski hill was finished.

The arduous labor was rewarded they following winter when the Victor ski hill opened with great fanfare. The first special snow train brought skiers from as far away as Pocatello on Sunday, January 30, 1938. The Idaho Falls newspaper reported that a large crowd attended this spectacular winter event, which included exhibitions of controlled skiing, jumping and slalom and downhill racing presented by regional skiers, Skiers and spectators were greeted at the train by the Victor High School band and whisked to the hill on horse-drawn sleighs, where bobsleds were also employed to transport skiers to the run’s summit.

The locals thrived on the excitement of their new ski hill, holding their first community ski meet less than a month after the grand opening. About 150 participants and spectators attended the event, which pitted Victor’s married men against its bachelors in downhill, slalom and short cross-country competitions, plus a cross-country ski race into town. The husbands were triumphant, winning a free public dance at the Log Cabin Inn hosted by the single men and featuring a local orchestra.

A group of Teton Valley skiers formed the Teton Ski Club to promote these local events and also to travel to other area ski hills, such as the rope tow on the top of Teton Pass where the Dartmouth Ski Team trained during the early season. According to Homes, the Teton Ski Club also attended ski meets at another little ski hill south of Pocatello.

Holmes was an early supporter of the club, which boasted up to 50 members, and he even served one year as the president although he never quite got the knack of the sport. “I was forever crossing my skis, falling down and spraining my ankle,” he recalls. “I would limp around the drugstore for 10 days, then I’d get up the nerve to go out and try it again. Then I’d cross my skis again and down I’d go.”

The drugstore stocked ski equipment and Homes says he sold a pair of skies to almost everyone in the valley. Poles were usually made of bamboo with a leather strap, and skiers used their own leather boots with a notch carved into the back of the heel to accommodate a cable binding. Store-bought skis were edgeless and made of solid wood; they cost about $30 with bindings running another $6.95.

Holmes remembers selling a pair of skis to a gentle man who’d never tired to sport, then later that same day watching the fellow’s progression. “He went up the hill to the brow of the hill where the steep part begins,” Holmes remembers with a twinkle in his eye. “He came down the hill and crossed his skis and id a header. He got up, dusted himself off, too his skis off and never did try it again.”

In 1939 the Victor ski hill employed W.C. Burns Construction of Idaho Falls to transport and run a sled lift powered by a big diesel engine. By steel cable, the engine pulled a flat-bottomed sled to the top of the hill in less than two minutes; in reverse the sled crept back down to the bottom to

pick up another backer’s dozen of eager passengers. On the first day of its use, the Teton Valley News reported: “The life made about forty trips up the hill carrying skiers and spectators alike. Many reported that the trip up the sharp inclines was as much fun as the trip down on skis. All commented that the fare of five trips for 50 cents or all trips for $1.00 was reasonable.” Proceeds were used to pay the lift operator.

The winter of 1940-41 was the area’s heyday, when it unveiled an improved access road and a new power line that furnished electricity to run a high-speed electric rope tow and the lights for night

skiing. The new lift increased the vertical drop to 850 feet, transporting skiers to the summit in just over a minute. The Teton Valley News reported, “The tow is easy to ride and for the nominal charge of $1.00 for me and 50 cents for ladies and high school students and 25 cents for kids one can get all the skiing possible in an afternoon.” Only a month after the start of the ski season, the rope tow was so popular that the Teton Valley New reported it had “reduced the number of spectators and converted them into skiers.”

Perhaps the only thing that could dampen the enthusiasm was a war. When the United States entered World War II, a lot of Teton Valley’s young men—indeed, its core group of avid skiers—bundled off to serve their country. Homes recalls that the Victor ski hill did operate for a few years more, but the sharply reduced participation, enthusiasm for it support dwindled.

After the war, the youngsters who had learned to ski at the Victor ski hill were beginning to start their own families and support for another community ski area once again began to build. A plethora of little rope tows and small ski hills seemingly sprouted everywhere throughout southeastern Idaho, providing good clean fun for the region’s youth at a price that wouldn’t

impoverish their middle-class parents.

June Penfold, who lives in Darby, has been skiing her whole life and was one of the baby-boom parents who wanted to pass her life passion on to her kids.

Born and raised in Victor, she was twelve when the ski hill opened in 1938. “I had a real good friend who had a sleigh that we used to take to the ski hill,” she says. Like kids today, she and her pals loved to swoop down the slope as fast as their courage allowed. “Nobody really knew how to ski and part of the hill was so steep—it was wild!” Sometimes the ski party would end with a bonfire at the base, and sometimes they would ski while roped behind the sleigh on their way do and from the hill.

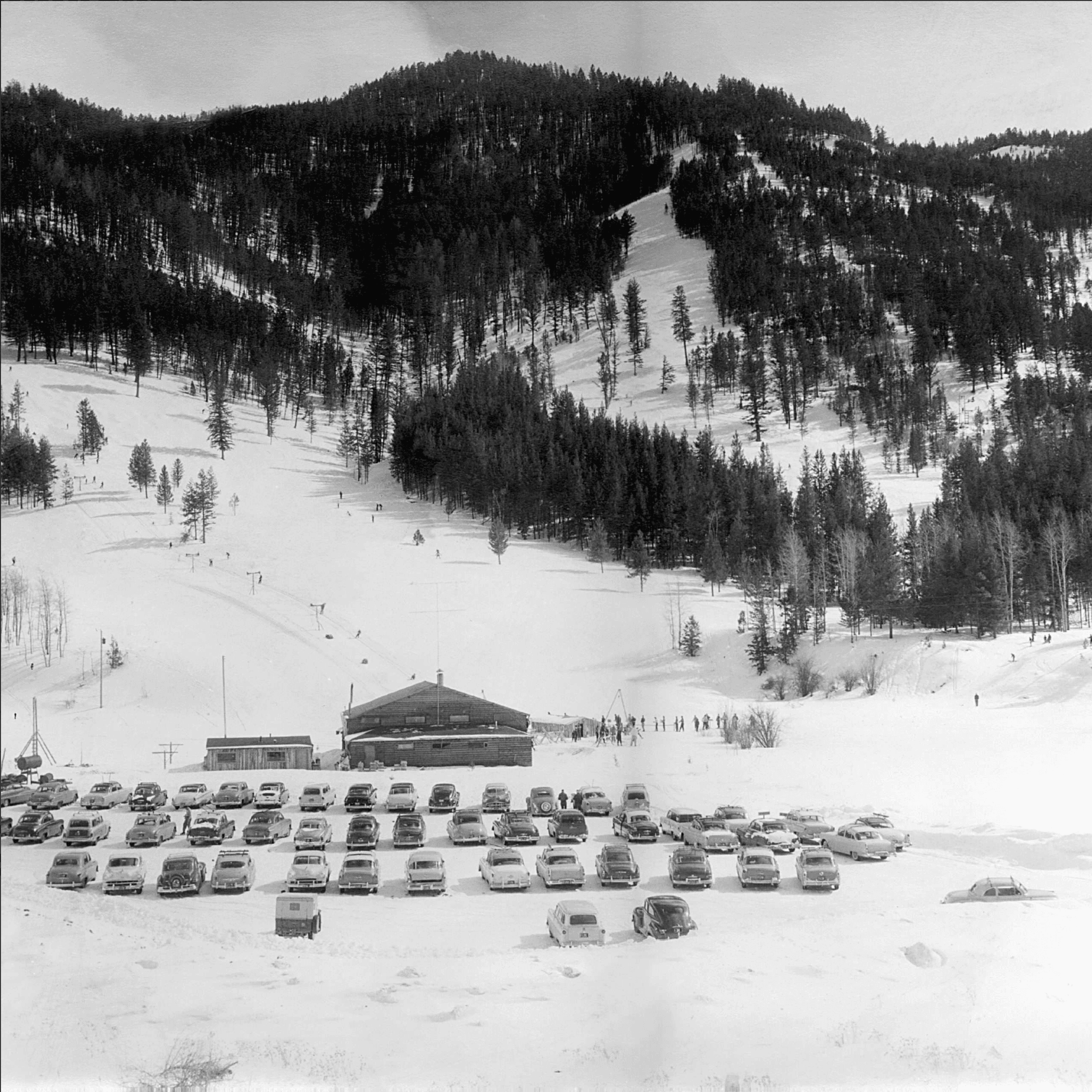

After the Victor ski hill closed down, June and her husband, Don, helped develop a new ski area at Moose Creek southeast of Victor. Dr LaGrande Larson owned the land and donated the use of an existing lodge for skier facilities. Two rope tows serviced the area: one for beginners and the other for more advanced skiers. Three runs were dubbed Sunnyhollow, Devil’s Corkscrew and Moose Face Run. The area opened in the winter of 1956-57.

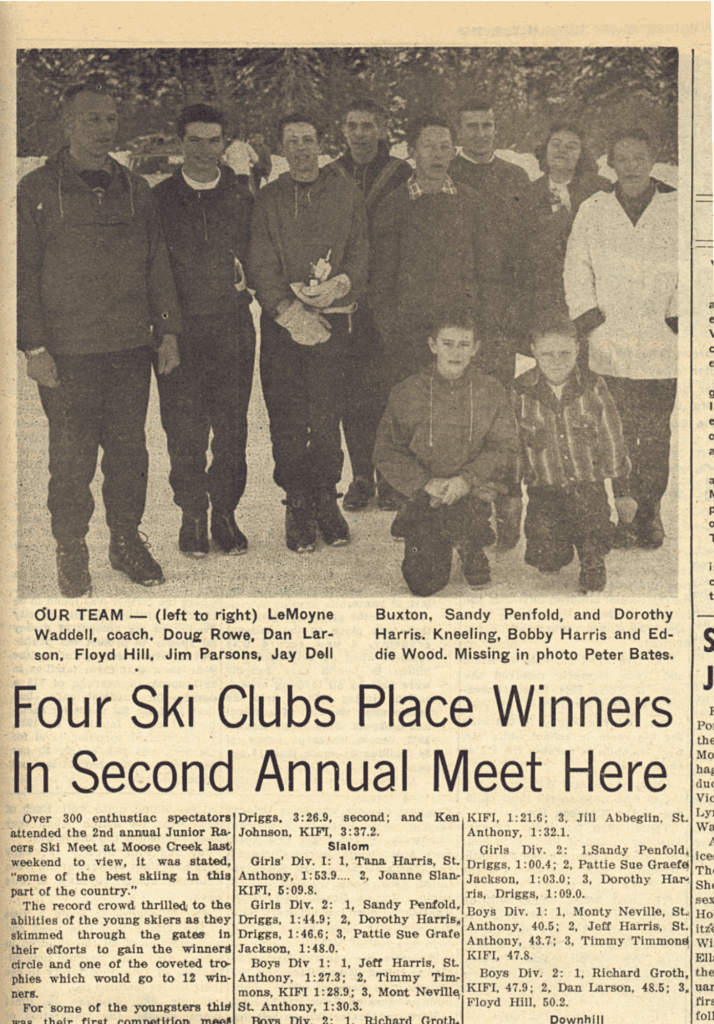

All regional ski areas supported various ski clubs; some were for all ages but most were especially for kids. In Teton Valley, the Moose Creek ski team consisted of high-school-age racers. Bates spud farmer Jay Dell Buxton participated with the team and says skiing at Moose Creek “was a great

social release for all the young people.”

Another local farmer, Gary Zohner was also on the team that raced every weekend, competing in slalom, giant slalom and downhill events. “I don’t really know how we were chosen, probably just if you could stand up on a pair of skis,” he speculates with a chuckle. “We went to quite a few races at Jackson and Bear Gulch. The final race was at Magic Mountain near Twin Falls. They had a T-bar and it was more advanced than anything else, but it was quite remote. It was about 15 to 20 miles up a rough old road to get to it.”

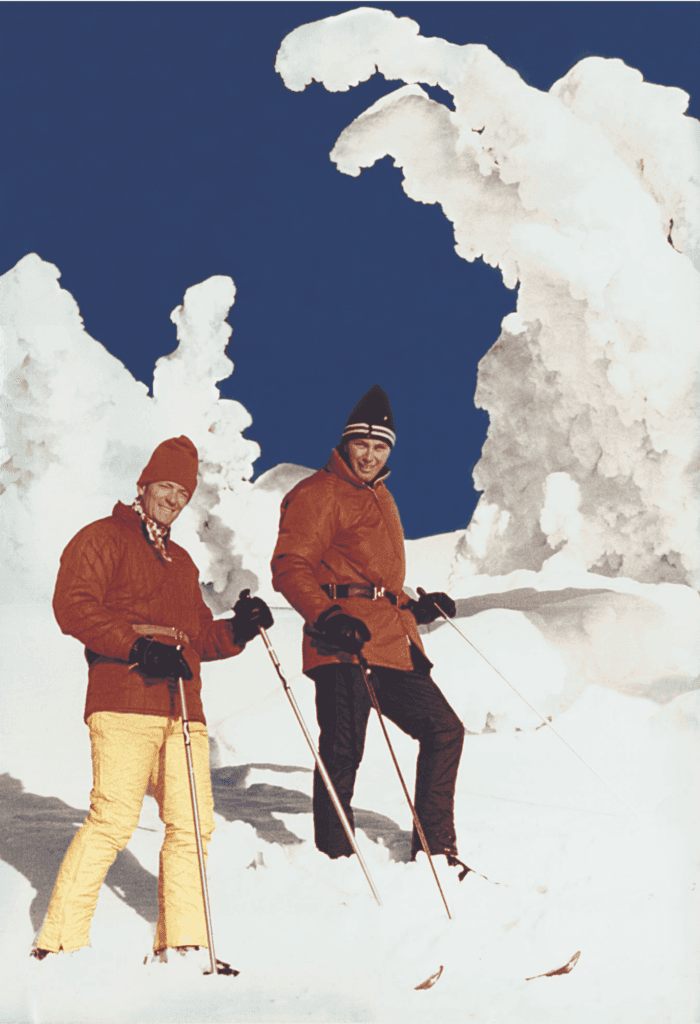

LeMoyne Waddell coached the team, later joining Grand Targhee’s first ski patrol when the resort opened in 1969. Waddell now lives in sunny Dallas, Texas, but his son Marc carries on the family tradition and is the first second-generation Targhee patrolman. According to Marc, his dad just

barely missed a spot on the Olympic ski team after honing his skills skiing for the military while stations in Alaska. “He came home from the service and they talked him into coaching us,” Zohner recalls.

For the away races, the Moose Creek ski team would pile into two cars for the trip, looking snappy in their homemade uniforms: a blue parka emblazoned with a red moose and “big old baggy ski pants.” Zohner and Buxton claim Sam Sewell was the fastest racer with probably the best technique on the team. After high school, Sewell joined the Ricks College race team, remembering in particular how angry his father was after he broke five pairs of skis during

just one season of racing. “My dad was about ready to cut short my adventures in racing, but I told him, ‘They just don’t make skis the way they used to!’” Sewell also joined Targhee’s first ski patrol, but now he tunes cars instead of racing skis while on the job at Sewell Auto Repair in Driggs.

Among the girls, Sandy Penfold was also quite an accomplished racer and often crossed the finish line first to the cheers of her parents, Don and June. Sandy now lives in Pocatello.

“My biggest memory is going over this jump that we made and seeing how far we could jump,” Buxton says. “We worked at it and we jumped quite a ways. And I can remember that because we had the opportunity of skiing there regularly, we became much better skiers than anyone that I knew who was older than us. If anyone older would show up, we’d just dust them. Our equipment was just better and we became very good skiers—all of us!”

Besides the big thrill of skiing at the “uptown” ski areas of Snow King and Sun Valley, the kids enjoyed racing at all the little areas, although Moose Creek was their favorite because it was the local hill. “You had to be pretty tough to ski on them (little ski areas) all day, just to hang onto the rope,” Zohner says. “We had a heck of a lot of fun.”

Ticket prices were kept as low as possible—just enough to cover operating costs. “We did it (developed Moose Creek) just so the kids would have something to do on the weekend. It wasn’t a money maker,” June Penfold explains. “The life tickets were maybe a dollar or a dollar and a half—and they complained about that! We didn’t make our expenses, but we didn’t care.”

Buxton remembers skiing as great cheap entertainment. “For two bucks you could have a hamburger and go skiing all day,” he says, which made the hill a popular diversion. On any given weekend, skiers had to wait in the lift line for up to 20 minutes because of the crowd. “It was a short hill,” he says. “You could go up to the top and come right back down, so you’d spend most of your time in line.”

“For two bucks you could have a hamburger and go skiing all day,” Buxton recalls.

Teton Valley supported organized skiing for younger children as well. Beginning in the early 1950s, the local PTA sponsored a ski program for the smaller school children. Prior to the construction of Moose Creek and after its closure, the kids were bused to Pine Basin, another ski area just over Pin Creek Pass toward Swan Valley. Pine Basin, whose sturdy lodge is still standing at the base of the hill, was developed by Dan Kelly and Jim Brady of KIFI Radio in Idaho Falls. They sold stock in Pine Basin Corporation in order to fund construction. For nearly 20 years, KIFI sponsored a ski school program where many eastern Idaho kids grew up on skis, including Bob Hoff of Idaho Falls. “My dad bought stock in Pine Basin in each of his kids’ names,” he says. “Nobody had any vision of any return on their money; it was just a way to do it.”

Hoff grew up near the base of Taylor Mountain just south of Idaho Falls. Like the Victor ski hill that fathered Moose Creek, Taylor Mountain was a kind of predecessor to Pine Basin. Hoff’s father helped build a multiple rope tow on Taylor that accessed the ski runs in four stages. “Nobody paid

to ski, they just ran it for fun,” he says, adding that a tent at the bottom was always warmed by a big bowl of bubbling chili.

By the early ‘50s, the area was abandoned, but in the mid-‘60s an old chair life was installed to entertain skiers for a few more years before undependable snow conditions once again caused Taylor’s decline.

“It’s kind of in a little bowl and it was a really fun little hill,” Hoff says, adding that the slope boasted about a 1,500-foot vertical drop. Tickets for the chair lift were inexpensive and the area drew a crowd of over a hundred skiers on a typical weekend day. He reminisces about how the lift would run until dark, when a bonfire would light the way as skiers gathered at the bottom to take off their equipment. Families and ski gear were stowed in old army surplus trucks for the trip back down the unmaintained mountain road. “It was like a train of five or six vehicles all plowing through the snow, kind of like a sleigh ride, going through the valleys and the hills with all the lights …

“There was something neat about both Pine Basin and Taylor Mountain in those days,” Hoff recalls. “It was just like a large family. Every time you went up the lift, you were sitting with someone you knew or else they knew someone you knew.”

Hoff believes today’s big areas are both expensive for families and lack the social connections those little community hills thrived on. Wes Deist of Idaho Falls agrees with Hoff. He was the ski school director for the KIFI ski school and has been skiing in the region since the earliest days of the sport.

“You knew everybody on the ski hill,” Deist recalls. “If I didn’t see you on Sunday, I called up on Monday to see what had happened to you.”

Deist remembers that names and faces of many of the thousands of kids who went through Pin Basin’s ski school. In fact, he is still teaching ski technique; this winter he is working at Kelly Canyon with the development team, a group of kids interested in progressing with their ski racing careers. “What’s amazing is that I am now teaching the grandchildren of people I taught at Pine Basin,” he explains. “If I’m lucky, I’ll get to teach some great-grandchildren too!”

The KIFI ski school got into full swing during the 1950s and during its final season in 1971 more than a dozen greyhound buses delivered up to 500 youngsters a day to be taught by a cadre of 20 to 35 adult instructors on Pine Bain’s slopes. “I think my fondest ski memories are at Pine Basin,”

Hoff recalls. “It was just really a good thing for kids in those days … the bus ride up was half the fun!” Hoff, his brother, a cousin and a friend were known as the “terrible four” at the ski area because “We certainly skied as fast as we dared!”

Trapper and Fools Paradise are two of the run’s names Hoff remembers. “Fools Paradise was supposedly the steepest one. It went off to the west of the lift. That was our favorite.”

Deist was on of the first members of the National Ski Patrol in Idaho and remembers that ski bindings in the early days were designed to keep the boot on the ski, not to protect the skiers from injury. “There were three things that could happen in a bad crash,” he recalls. “One, you could pull all the screws out of the binding; two, you could break your ski; three, you could break your leg.”

Neil Rafferty, who managed Snow King, also ran the little rope tow on top of Teton Pass when Deist first skied at those areas. “He would hand me a first aid belt in the morning and say, ‘Here, patrol for me today,’” Deist says. In exchange, he’d get a lift pass for the day.

The Teton Pass rope tow had the best early season snow in the Tetons, Deist remembers, but the rope was rough on muscles and on gear. “People wore big gray horsehide mittens, thick almost like boxing gloves,” he says. “If you wore your good gloves, you’d burn through them in a day.”

According to Sam Sewell, that rope tow inspired a holiday tradition for his family—the brothers consistently chose powder over pumpkin pie. “If there was snow on Thanksgiving, we’d go skiing and eat our Thanksgiving dinner late at night.”

In those days, according to Deist, Teton Pass skiers could also ski down off Chiver’s Ridge through the trees and a jitney would pick them up at the road. Five cents bought a ride back up to the top.

Later in his career, Deist brought a young group of racers to Moose Creek to compete against the Teton Valley team. “I’ll never forget the slalom course,” he says, laughing at the memory.” In order to cross the finish line, you had to cross a little bridge and as I recall, you had to hit it real straight to make it across!”

For a time, Deist also ran a ski school at Bear Gulch near Ashton, another popular area that entertained local skiers for almost five decades. Like the Victor ski hill, Bear Gulch was developed by the community as a government work project and opened in 1938 with a sled lift. By 1940, a rope tow had augmented the skiable terrain and it cost ten cents per ride for the sled life and five cents per ride or $1 per day for the rope tow.

Bear Gulch also declined during World War II, but the dedicated locals re-established the hill in 1945 and ran it until 1970, when competition from the newly opened Grand Targhee resort made it economically unfeasible to operate as a community effort. The area ran sporadically for a few more years under several private owners, but the U.S Forest Service permit was finally allowed to expire. Area residents were saddened when in 1986 the U.S. Forest Service burned down Bear Gulch’s beautiful log lodge rather than rehabilitating it for another use.

Carol Marotz lives just down the road from Bear Gulch, located south of Mesa Falls. One of the founders of the hill, she still grieves for that old lodge while treasuring the memories of skiing there with her husband and four children. “I raised my kids here in Bear Gulch,” she reminisces.” We skiied that hill from the time it was opened until it closed 50 years later. It was just a lovely family hill.

“Bear Gulch had some of the best hills in the country for downhill racing, but the runs were short. They were steep; they rivaled some of those over to Jackson,” If the kids could ski all the hills at Bear Gulch, they could go down anything at Jackson.”

Other clubs came to race at Bear Gulch, including Teton Valley’s team from Moose Creek. Marotz’s son Don used to compete against Paris Penfold, Don and June’s son. Paris started skiing when he was only three or four years old. “I still have Paris’ boots,” explains his mom. “They were about five inches long.”

“I can still remember when they had races at Bear Gulch,” Paris says. “They had races for the little kids that they called the termite races. The course would take us about a third of the way up the hill and they’d line us up in a single line across the hill and the first one across the line won. It was fun. It was steep enough that you had to make a bunch of turns, you had to negotiate your way down there. If you fell down, you’d be at a disadvantage.”

During its prime, Bear Gulch sported a T-bar lift, a double chair lift and three rope tows. With its challenging terrain, inexpensive lift tickets and easy accessibility, the area spawned a whole generation of skilled skiers, many of whom later became supporters and even employees of Grand Targhee.

Leon Martindale of Ashton is one of those “Bear Gulch stump jumpers,” as they were affectionately known, and a former mainstay in the Grand Targhee ski school. He best remembers Bear Gulch’s expert, black-diamond runs: Bear Cat, Dipper and Grizzly. The slopes were precipitous and with no modern grooming equipment, the snow would quickly “bump up” into intimidating moguls. “It was a very steep hill and you had to graduate quickly,” he says. “You had

to know how to ski or you just didn’t make it!”

The beginner areas were groomed the old fashioned way—by hand. Local kids earned their season passes by packing the mountain manually. “It was a lot of work,” Martindale recalls. “If we got powder, why the whole crowd that was there would start packing the hill.”

With the North Fremont Ski Club, Martindale traveled to ski areas throughout the whole region. He even remembers skiing on a short slope on top of Pine Creek Pass where and impromptu rope tow was installed for a season or two. The club also skied at the short-lived Sunset ski area, whose rusting chair lift is still visible right off the main highway north of Island Park, just past the Ennis turnoff. “Sunset wasn’t very good at all,” he recalls. “It was too narrow and it was a lot of bumps where the snow would get packed down. Plus the lift was always broke down. He had a terrible time keeping the lift going.”

Marotz claims that the lack of a flat run out at the bottom of the steep hill was Sunset’s major problem and Martindale agrees. “The highway was your stop,” he says laughing at the memory.

All the kids in the region held a special place in their hearts for Snow King ski area in Jackson Hole. “At the time if you drove over to Snow King, and that was my all-time favorite hill (and still is),” Hoff says, “it cost $2.50 and you could stay at the Wort Hotel for $9.50.” Snow King was a true ski resort, but also an ultimate community hill, within easy walking distance of town.

“There was a caterpillar engine up on the top that ran the lift. You could hear that thing all through the town of Jackson. At the time, Jackson Hole wasn’t much bigger than Driggs,” Buxton recalls. “Snow King was really a first-class place. That was a huge hill in its day.”

The old places are mostly gone now, leaving only an outline of a run and the occasional rusty lift tower or rotting ski cabin. For those who played on the slopes, many warm memories remain. Those little ski hills not only provided cheap entertainment, they brought communities closer, creating a cohesiveness of spirit in their support of healthy activities for the youth.

Today, the tradition is carried on at Grand Targhee Resort, where a ski school program provides opportunities for Teton Valley kids at discounted prices (free for those five and under). And the Teton Valley Ski Education Foundation offers an outlet for young athletes, providing affordable winter sports education for them to meet their individual potential for excellence through education and opportunity for competition.