Born of Necessity

Since the first permanent settlers arrived to stake their claims in Teton Valley in 1882, two things have always seemed in abundance: wide-open spaces and newborn babies. As pioneers moved west across the land they learned out of necessity how to care for their own: isolation left medical care in the hands of the people themselves.

Roots run deep in Teton Valley, and most longtime locals have a story to tell. If they don’t have a grandmother who was a midwife, they certainly have relatives who were delivered by one. J. Valone Nelson recalls that an Indian midwife delivered her father, Leigh Fullmer, in 1898 near Leigh Creek. In fact, midwives have been an important part of all times. Undoubtedly one of the world’s first professions, midwifery is mentioned in Genesis 35:17. “And when she [Rachel] was in her hard labor, the midwife said to her, ‘Fear not, for now you will have another son.’” Exodus 1:20 reads, “Therefore God dealt well with the midwives and the people multiplied and waxed very mightly.”

As the pioneer companies of Mormons moved west, most brought their own midwives with them. These women were held in the highest regard. In 1902, the Relief Society inaugurated a school for nurses, according to the 1963 records of Kate B. Carter of the Daughters of the Utah Pioneers. The school’s principle teacher, Dr. Maggie C. Ship Roberts, traveled to Teton Valley in the early 1900s to train local Mormon women.

According to Donald F. Coburn, whose essay “Our Mountain Home So Dear” appears in Spindrift: Stories of Teton Basin, the customary fee for attending a delivery and providing three days of care was $5, but often the mothers could not pay. The midwives were obligated to accept a fee of as little as $1 to $3, or trade their services for farm commodities like eggs, meat or vegetables. These angels of mercy regarded their work as missionary service and would accept nothing at all if that was what the family had. Coburn recounts valley resident Ruby Schiess’ memories of her mother, Clara Miller, who was a midwife. He says Ruby remembers “her mother coming home from one delivery and telling her father that the new mother and her family had no money, not even any milk for the baby. The next morning Ruby saw her father going up the road with a wagon of hay and a new little heifer tied on behind.”

The surnames found on a list of midwives from History of Teton Valley Idaho by B. W. Driggs, matches the social geography in Teton Valley today. Lois Ann Eynon, Lavina Drake, Lizzie Curtis, Susan Jones and Clara Miller practiced in Victor. Melissa G. Homer and Caroline B. Rammell set up shop in Haden. Darby residents looked to Anna Peterson Larsen. In Bates, it was Mary Piquet. Pratt was home to Sophia E. Rigby, Emma Pratt, Sarah Hulet, Lucy Brown, Anna Carlsen and Harriet Davidson. Clawson residents called on May Allred Barney, Mrs. William Hubbard, Mary Beard and May T. Shaw. Finally, Emily C. Beesley, Lydia Manette Hillman, Elizabeth Langton Driggs, Alice Carson Buxton and Rosa Shaw Henrie practiced in Driggs.

Because they were the only residents with medical training, many of the midwives took the sick and injured into their own homes. There are numerous reports in the Teton Valley News from 1922 to 1924 of people recovering from complications of childbirth, flu and pneumonia in the home of Mrs. E. Beesley. Travel problems were somewhat mitigated after 1918 by the establishment of two maternity homes in downtown Driggs, first by Alice Carson Buxton and later by Lydia Manette “Nettie” Hillman. According to Ronell Breckenridge, granddaughter to both women, they provided expectant mothers with three meals a day along with prenatal and postnatal care for an average of 10 days.

Alice, whose husband was killed in a logging accident in 1904, was having trouble providing for her seven children, so she left the valley for Salt Lake City in 1915. There she graduated from the 9-month LDS nursing program. After working in Salt Lake City for two years, she was persuaded to return to the valley in 1918 and open a maternity home. By the time she retired in 1941, she had assisted in 612 births. Her home was a busy but orderly place. “You were always very quiet when you went to Grandma Buxton’s house,” Ronell remembers.

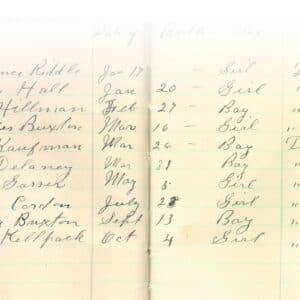

A few years later, in 1921, Nettie Hillman also suffered the tragic loss of her husband and needed a way to meet her farm bills. According to Ronell, “Grandma Hillman saw what Grandma Buxton was doing and figured she could do the same thing.” Affectionately known as “Grandma Hillman” or “Aunt Hillman” to most of the rest of the community, Nettie opened her two-room maternity home in 1920. She had attended about 150 births before opening the home and recorded 235 more in her new residence. By all accounts Nettie was an extraordinarily kind and giving woman who never refused a patient, no matter how poor, including the transient workers who picked vegetables. Nettie often had a full house and would sleep on the couch. In a history of her grandmother, Ronell writes, “Every new baby was a bit of heaven to her and every mother was like a daughter. She could make a baby quit crying by just holding it and talking to it. Every baby seemed to know she loved it and it was special.”

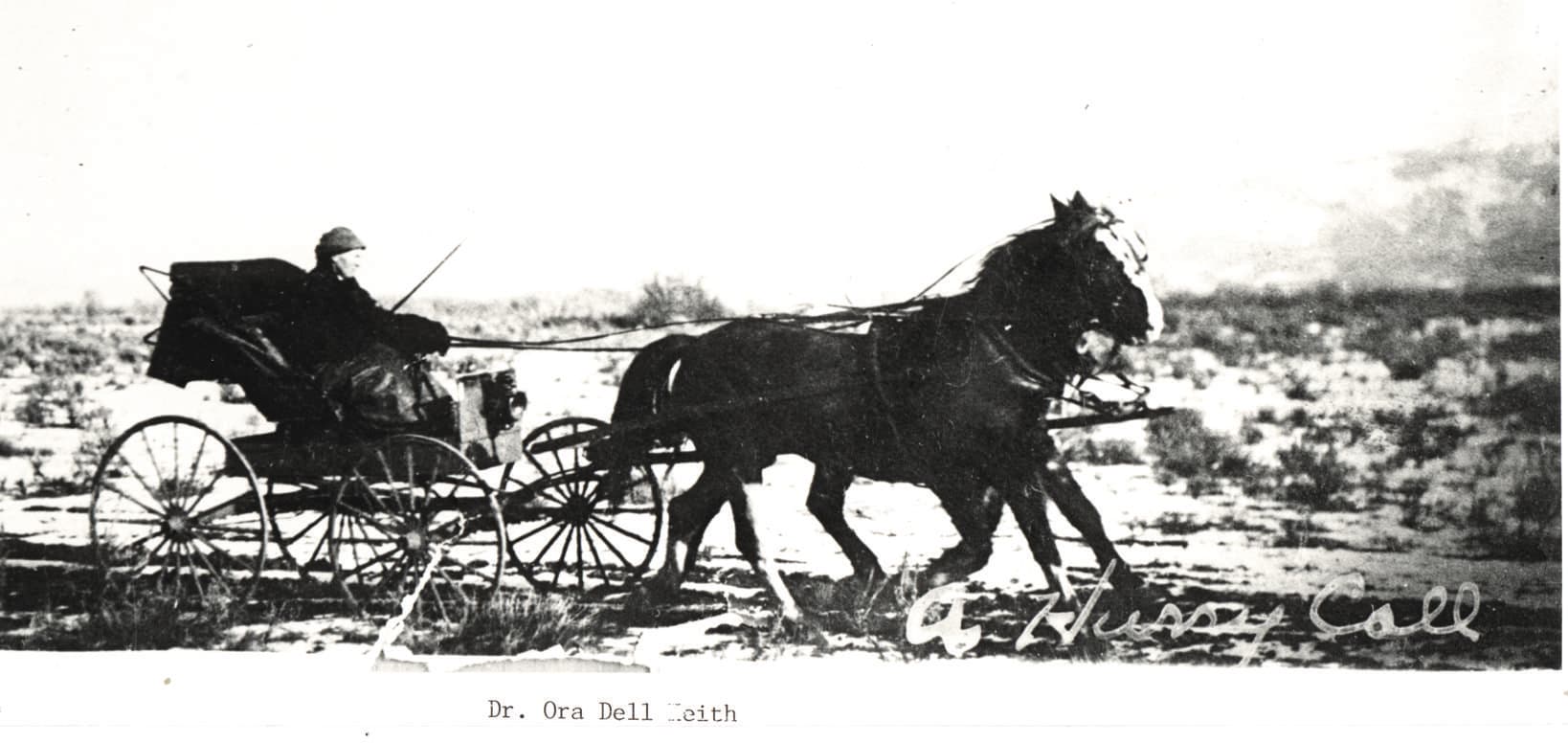

A few medical doctors did practice in Teton Valley from 1893 on, but it appears that until 1925 there was never more than one at any time. Physicians who attended births at Buxton’s and Hillman’s maternity homes include Dr. Redner, Dr. George Parkinson and Dr. Gavin. The most renowned doctor in the valley was an unmarried woman named Dr. Ora Keith who practiced in Driggs from 1906 to 1915. According to History of Teton Valley Idaho, she had a “fractious team of horses and knew how to handle them well. The snow was never too deep or the blizzards too rough for Dr. Keith. It was common practice all over the valley to name the babies Ora or Keith depending upon the sex.”

In some of Dr. Keith’s correspondence to friends, reprinted in the Teton Valley News, she recounts her trials with disease and distance. “Some new babies came and many different sicknesses, which kept me very busy and my team and self too tired.” Sometimes she received two calls simultaneously and had to decide which was more urgent. In 1914 a scarlet fever epidemic left her exhausted. She wrote, “I was weary. I settled myself down and said, ‘Now for one hour in which I hope to read, think and rest,’ but the thought had scarcely formed into words when ‘Ding-ling, ding-ling’ when the phone and a distant voice said, ‘Come quick, our baby is very much weaker.’”

The term midwife literally means “with woman.” To most mothers birth is a frightening proposition, and the long-standing rituals passed down through generations have always included the support of other women. Only in recent history have doctors and medicine become a routine part of the birthing process. By the 1920s, childbirth was often attended by a “professional.” Doctors, with their many devices and drugs, promised to shorten labor and reduce pain and soon developed extensive family practices. With the construction of the Teton Valley Hospital in 1938, the role of the midwife became less essential.

According to Jessica Mitford, author of The American Way of Birth, midwives attended about 50 percent of births in 1900. By 1935 that number had fallen to 12 percent and in 1986 only about 4 percent of pregnant women chose the assistance of a nurse-midwife. Midwifery was considered unscientific and therefore became less respected. As births became institutionalized, it passed out of the hands of women.

Midwifery has only recently begun to rebound. “Midwifery care exists in Teton Valley. It doesn’t look the same as it once did, but the thread, the current, is still alive,” says Theresa Lerch, a certified nurse midwife (CNM) and family nurse practitioner (FNP), who sees patients at the Victor Medical Clinic twice a week and works with Jackson Hole OB-GYN PC.

She and one of her partners, Kathy Watkins-Brecheen, also a CNM, hold bachelor’s and master’s degrees in nursing, and both are board-certified and fully licensed. Today only five CNMs practice in Wyoming, with an estimated 25 to 30 in Idaho, where a CNM can legally attend births in homes, birth centers or hospitals. “Direct entry” or “lay midwives” do exist and attend home births, but they are not licensed and none are known to be practicing in Teton Valley.

Lerch and Watkins-Brecheen provide almost all the same services as a physician, major surgery excepted. They do have a referral relationship with the physicians in their practice, and complications or high-risk pregnancies are handled in conjunction with the OB/GYN doctors. According to Watkins-Brecheen, midwives stand apart from traditional physicians in that they see childbirth as a special family growth process as well as a medical condition. “We offer specialized care—a more intimate relationship centering around the family and the child.”

Today’s midwives blend the old and new techniques of childbirth. Because they have such a high degree of medical training, they provide maximum safety while bringing back the relationship skills associated with woman-to-woman contact. Many expectant mothers believe a birth attended by a midwife will be both safe and easy. They trust in nature and the way their bodies are designed to give birth. “People feel most comfortable in a home setting. They have more control and are more aligned with their values,” says Pauline McIntosh of Victor, a retired midwife.

The expectant mother and her caregiver endured remarkable hardship back when Teton Valley had few roads and bridges—especially during the Rocky Mountain blizzards that make driving even a 4-wheel-drive SUV impossible. In such a remote and hostile environment, any complication of childbirth could spell disaster. So it’s not surprising that oldtimers view the traditional way of life with little romantic nostalgia. “Well, things were hard, but we didn’t know it,” valley native and local historian Guy Nelson, 81, muses. “Everyone was in the same situation. We didn’t know ‘til later how hard it was.” Back then people learned out of necessity that it took a community effort to survive, and members each contributed a special skill. While few would savor a return to the self-sufficiency of the old days, it’s important to note how that mentality bred the community Teton Valley celebrates today.