Cal Carrington Old Time Buckaroo

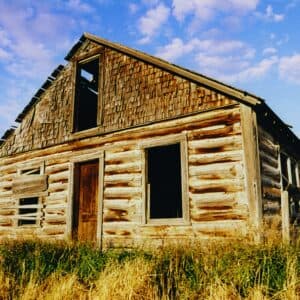

In the fields southwest of Driggs, a timeworn cabin sits off the Bates Road about a half mile east on 125 South and a hundred yards north. Few today realize this simple structure is steeped in western lore.

Oren Furniss—born in 1918 on an adjacent homestead—farms around the 110-year-old shack, preferring to preserve it rather than remove it. Oren was a friend and neighbor of the cabin’s original owner, Enoch “Cal” Carrington, a legendary figure in both Teton Valley and Jackson Hole. Victor resident Grant Thompson’s father was born in the cabin in 1919, when the family was leasing the property from Cal. And Orville “Jack” Buxton’s boys, Farrell and Jaydell, recall their family renting the surrounding ground in the 1950s to grow hay; theywould visit the cabin to hear yarns from the old cowboy, who spent his final years there.

Besides what Cal called the word machine (typewriter), and talking furniture (radio), the cabin held other curiosities, the Buxtons recall, like a huge mounted rhinoceros horn and a fly swatter made from an elephant’s tail. A tuxedo and suit hung in the closet, while horse harnesses dangled on the wall next to it. In the attic, a set of matched pistols sat on top of a trunk containing personal papers.

In autumn 1959, when he was eighty-six, Cal’s health began to deteriorate. Seriously ill, he checked into the hospital in Jackson. There a selfproclaimed preacher took it upon himself to visit Cal, imploring him to commit to God. Delivering a few choice cuss words, Cal crawled out of bed, donned his clothing, and never went back to that hospital.

By Christmastime, though, Cal lay dying in the Driggs hospital. He had always been tight-lipped about his early years, reinforcing rumors he had once been a horse thief. During one interview, when Cal was asked where he had been before coming into the valley, he’d growled: “That’s none of your damn business.” But on his deathbed, the old buckaroo loosened up and related some details about his life.

Cal Carrington was born Enoch Kavington Julin in Orebro, Sweden, on February 10, 1873. As a young child, he was given away—terrified and weeping— by his zealous family to Mormon missionaries proselytizing under Albert Carrington, an Apostle of Twelve and presiding authority over European Missions. Taken to Utah by the immigrating Saints, he was raised, he recalled, under harsh frontier conditions. He later resentfully claimed, “My education was on the back doorstep.”

Enoch hated the stern Mormon elder who was the head of his foster family. “When I was sixteen,” he later said, “Ibeat hell out of the S.O.B. and run away.” He never forgave his real family, either, or Mormons in general. Because of these sour feelings, he chose his own first name, California, which he shortened to Cal. He continued using Carrington, although he was no relation to his Mormon namesake.

An orphaned saddle tramp, the boy drifted south to an Arizona cow camp where he learned to ride and became a top cowhand and bronc rider. He hired on as a drover for some of the last great open range cattle drives, trailing cattle from the Southwest to mining camps in Montana. It was a rough life for a young man; after one such drive, he related, two of the cattle owners had a “row amongst themselves” and one killed the other.

In spring 1897, Cal and a traveling companion, James H. Berger, came into Teton Basin on a rattling, lightweight iron-wheeled wagon. They were looking for new country, adventure, and a livelihood (little different than many of today’s arrivals). Years later, Cal reminisced on his first impression of the valley: “Grass, grass everywhere—it was a good place to picket a horse.”

Cal squatted—took up residence without title, a common practice back then—on a 160-acre tract near Bates. He constructed the stout cabin and filed for water rights on what he claimed were surplus waters from John Holland’s spring, near Horseshoe Creek. Later, he filed for water rights on Mahogany Creek, according to claim records in the Teton County Courthouse in Driggs.

Berger took up a homestead a mile northwest of Cal, eventually marrying a local woman and moving to Victor. Recognized among the valley’s early pioneers, Berger is buried in the Victor Cemetery. He and Cal were among those who settled under the Desert Entry Land Act, legislation passed specifically pounds, with taffy-colored hair, clear blue eyes, a narrow waist, a great chest, and large hands. Jackson Hole wrangler Rex Ross once said, “While Cal didn’t look like a real tough guy, he was. He was afraid of no one.” Cal boarded and worked with some of the Hole’s original settlers. “Jackson’s old-timers” as he called them, included to encourage the economic development of the dry public lands of the western United States.

A settled-down life wasn’t for Cal, though, and in 1898 whisperings of adventure lured him across Teton Pass. He arrived empty-handed: “When I first rode into Jackson’s Hole, I didn’t have nothin’ but a long rope and an old buckskin horse,” he later said.

As a grown man, Cal was described as over six feet tall and nearly 200 pounds, with taffy-colored hair, clear blue eyes, a narrow waist, a great chest and large hands. Jackson Hole wrangler Rex Ross once said, “While Cal didn’t look like a real tough guy, he was. He was afraid of no one.”

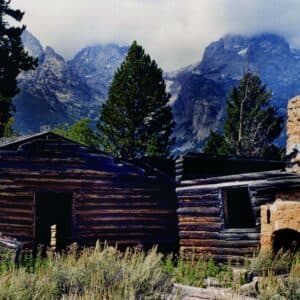

Cal boarded and worked with some of the Hole’s original settlers. “Jackson’s old-timers” as he called them, included Holland, who had been the leader of the posse that gunned down alleged horse thieves at the Cunningham Cabin (and was a witness to Cal’s Desert Entry application); Dick Turpin, a fiery, bushybearded pioneer rumored to have killed a man; Robert Miller, who bought horsethief Teton Jackson’s land claim and cabins from him and in 1914 helped launch the Jackson State Bank; and Charles “Pap” Deloney, who pioneered the first general mercantile store in the Hole.

“Living with Pap … the way I did, I lived as good as the rest of them … it cost me about ten dollars a month,” Cal once said. At times, too, he stayed at an old trapper’s cabin in Flat Creek Canyon, where, he said, “I could spot a sheriff a comin’ an’ a goin’.”

Later published accounts of this period allege that Cal apprenticed to rustlers, lived with Indians, saw the inside of a jail, was in San Francisco during the 1906 earthquake, and escaped a posse by swimming his horse across the ice-swollen Snake River while clinging to its tail.

Rumors in Jackson also had him mixed up with several notorious gangs; groups that had, rightly or wrongly, earned colorful reputations for lawbreaking. A polished-appearing Cal, with poodle and silk stockings, at Cissy’s mansion in Washington, D.C., in the early 1940s. Hearsay maintains all the outlaws were captured, except Cal.

Victor historian Wendell Gillette, in The Memorable Character—Cal Carrington , published in a regional historical journal, chronicled similar tales: “A horse thieving ring was established among Cal and five other men…” Two of these men Gillette identified as Teton Valley’s Ed Harrington and Lum Nickerson, both busted for rustling in 1887. According to Gillette, they drove their stolen horses across the Tetons on novelist Owen Wister’s “horse thief trail” (Conant Pass) and used Cal’s property to change the brands, after which they’d sell the ponies to unsuspecting buyers.

However, Gillette’s account, like many pertaining to Cal, is out of chronological context; it refers to events taking place a decade before Cal even moved to Teton Valley. While these stories are entertaining, many are unverifiable; canards of the sort folk back then amused themselves with—a practice Westerners called “stuffin’ dudes.” If wide-eyed greenhorns and journalists picked up on scuttlebutt and passed it along as fact, all the more fun.

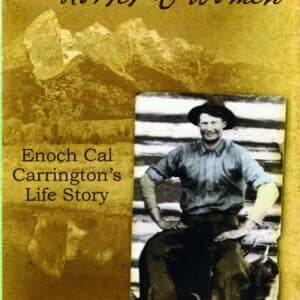

What actually occupied Cal in his early years in Teton Valley and Jackson Hole is described in my forthcoming book, I Always Did Like Horses & Women: Enoch Cal Carrington’s Life Story . Contrary to traditional lore, it was not the pre-owned horse business that Cal was involved in. But still, his life was plenty wild and woolly, full of escapades of the sort that have contributed to the growing legend of the American cowboy.

Cal wasn’t beyond spreading the legend himself. When Theodore Roosevelt came through Rexburg on his September 1900 vice presidential cam- Rumors in Jackson had Cal mixed up with notorious gangs and outlaws. paign, Cal recalled, “John Holland and I rode down there … that’s thirty-five miles. I was going to ride a bronc [for Roosevelt] … [but] it wouldn’t switch its tail. [The] crowd was so thick the horse was scared to death …”

Around 1912, Cal hired on as foreman for the Bar BC in Jackson Hole. The ranch’s owner, acclaimed author Struthers Burt, credited Cal with instructing him “in the ways of ranching, livestock and the hills.” Contradicting popular gossip, Burt wrote in a magazine column titled The Most Unforgettable Character I’ve Met , “I have never known in all my life a more honest man …” When the Bar BC became the Hole’s second dude ranch, Cal was made head guide in charge of pack outfits.

A more widely known part of Cal’s life begins in 1916 with the disembarkation at the Victor railhead of Chicago Tribune fortune heiress Eleanor “Cissy” Medill Patterson Gizycka—aka “the Countess”— and her daughter Felicia. After boarding overnight at the Killpack, Victor’s largest and most luxurious hotel, Cissy and Felicia arrived at the Bar BC late the next evening, soaked in rain and covered in mud after being “dragged acrost” Teton Pass in a crude ranch wagon.

The wealthy socialite was drawn to Cal, a ruggedly handsome and charismatic man. Their pairing up was one of the most glamorous, jawed-about “dudecowboy affairs” in Jackson Hole and the West. Together, they homesteaded the Flat Creek Ranch, became widely known as “the hunting couple” from Jackson, ran the Salmon River in a crude raft, traveled to Europe, attended lavish parties in the East, and firmly and forever embedded themselves into the Hole’s early history. Long after she’d permanently left the West, and until her passing in 1948, Cissy referred to her cowboy as “dear old Cal.”

Fueled by knowledge and opportunities gleaned from his association with Cissy, Cal became a gadabout and longdistance wanderer. In Chicago, he met opera singers, actors, Follies girls, and millionaires. In Philadelphia, he hunted foxes with the equestrian elite; in New York, he was honored with a dinner and seated beside a French countess. He attended the 1927 Dempsey-Tunney fight at Soldier Field in Chicago and, following that, took passage on an East Indian freighter to East Africa, where for more than a year he traveled and hunted big game. In 1930, according to U.S. Census records, his peregrinations took him to the gold fields of Nome, Alaska.

It was all a world away from Bates. But by the late 1930s, Cal had given up the vagabond life and returned to Teton Valley, ranching and growing ninety-day oats. The work proved tougher for Cal than it had once been. In spite of a lifetime around dangerous stock, he was badly injured on his farm by a horse named “Scrubby.” Neighbors at Bates looked in on him and helped out until he recovered.

At age seventy, while hauling firewood out of the Big Holes, Cal had another mishap with a stock animal when he was unable to check a new horse he had bought from Forest Ranger Frank Moss. He was thrown from and run over by the heavily loaded wagon, severely fracturing an arm and a leg. He struggled down Twin Creek in the dark and cold with bones protruding. Back home, he wouldn’t allow neighbors to take him to the hospital until he was cleaned up. “I wasn’t a-goin’ to let no pretty young nurses see me in no shape like that,” he said.

Cal was eccentric and cantankerous in his later years. Some local folks remember him best from contentious water-rights disputes. According to one valley rancher, “Carrington enjoyed being an authoritative know-it-all.” A friend said to him, “Why don’t you quit that foolishness … fighting with your neighbors.” Cal burst out, “Well, I’m too old to ride in rodeos. I can’t steal no more horses … My God, I’ve got to find something that is entertainin’.”

Years earlier, Cal had quietly acquired beachfront property in Encinitas, California, where, throughout the 1950s, he’d retreat to each winter by Greyhound bus. Tetonia rancher Dale Breckenridge recalls a valley barbershop witticism from that period: “It must be spring—the sandhill cranes and Cal Carrington are back.”

On Christmas Eve, 1959, the Teton Valley News front-page headline announced, “‘Cal’ Carrington Early Pioneer Dies.” His passing was greeted with sadness by those who saw it as representing the end of an era, and, when his will was read, with low whistles by those surprised at his net worth. While Cal had lived his last years in relative squalor, his wealth was the equivalent of millions measured in terms of today’s dollar. Later, his Bates cabin was scoured by vandals seeking valuables they thought he may have hidden there.

Cal Carrington is buried in Jackson’s Aspen Cemetery. What he left for us all is a legacy of western lore and stories that figure richly in the mythos and legends of early day Jackson Hole and Teton Valley.

This story first ran in the Summer 2008 edition of Teton Valley Magazine. The tale was adapted from the author’s published book, I Always Did Like Horses & Women: Enoch Cal Carrington’s Life Story. Research and writing for the book took more than four years. It involved some three dozen books; twenty-four journal and magazine articles; numerous newspaper stories; two oral interviews (recorded with Cal more than fifty years ago); conversations with more than two dozen individuals who knew Cal or otherwise had information about him; papers and letters from privately held family collections; dozens of websites; and materials from local, state (Idaho and Wyoming), and national archives and museums.