National Outdoor Leadership School —Teaching Respect for Nature

In 1998, Backpacker magazine editors decided to hand out Silver Service Awards to commemorate the publication’s 25th anniversary. They vowed to honor “the backcountry equivalents of Microsoft and Ted Turner,” the most monumental of the past quarter century’s major contributions to making wilderness experiences more enjoyable.

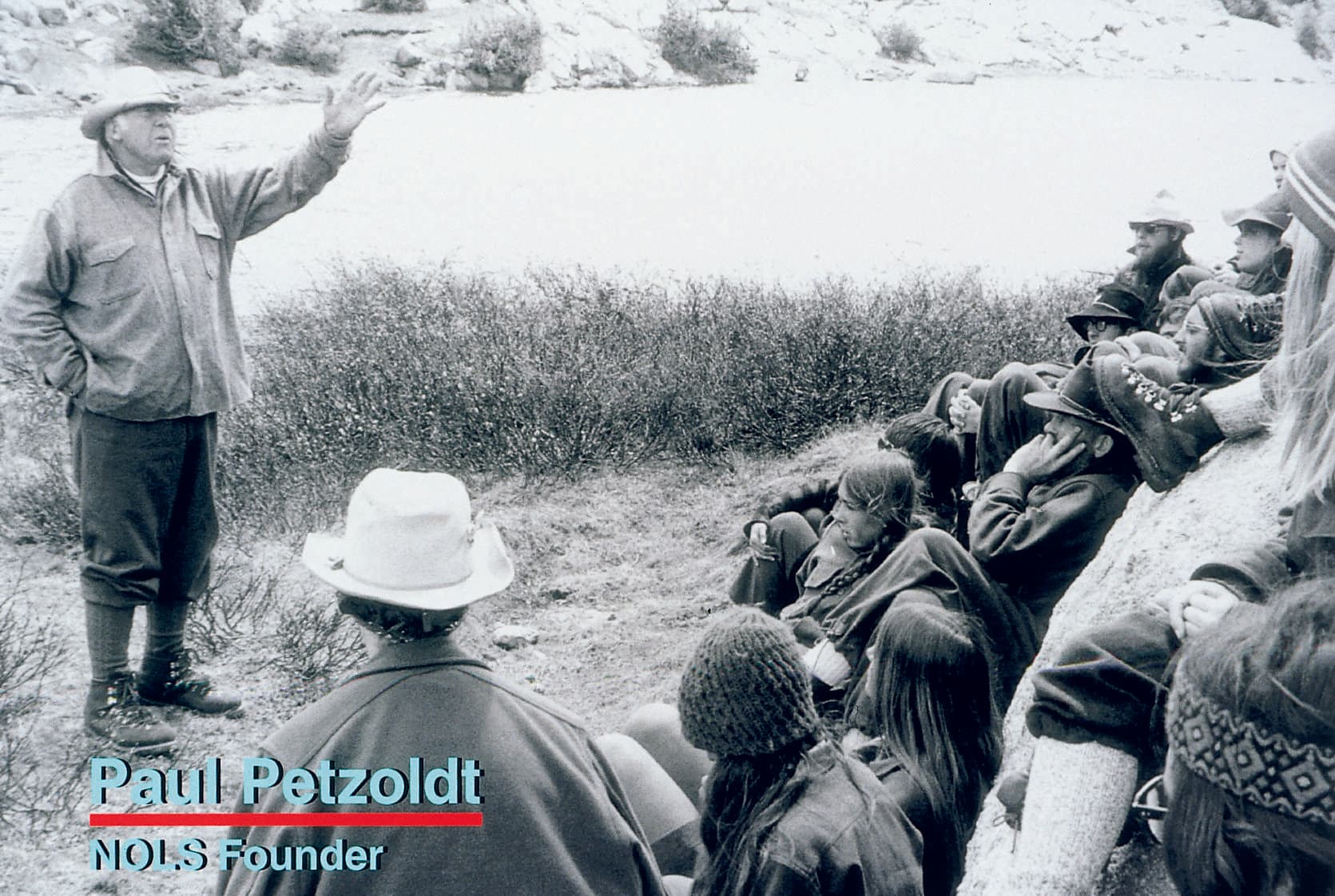

The contenders were legion, and some legendary. In part, renewed awareness of the outdoors had defined the preceding few decades. Editors had favorites as diverse as internal-frame backpacks and Velcro. Passions ran high. But when they all shouted, “We love you, Man!” and stuck out their metaphoric fistfuls of wildflowers, the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) and founder Paul Petzoldt’s concept of “Leave No Trace” were both among the nine award recipients. NOLS shared the limelight with Edward Abbey, the Sierra Club and Polartec.

Paul Petzoldt died in 1999, but his legacy of experiential teaching, outdoor adventuring, good judgment, self-reliance and wilderness stewardship gives his life resonance. He spoke so often and so passionately about safe outdoor adventuring that his thoughts live on today in the public domain. Popular “Paul-isms” are often quoted when wilderness ethics and backcountry recreation are discussed. NOLS and its presence in Teton Valley are Petzoldt’s legacy.

Petzoldt began mountaineering as a youngster. At age 13 he led a friend and his dog, Ranger, into Idaho’s Sawtooth Range. Looking back on that expedition he wrote, “I realized the mountains and wilderness were indispensable to me.”

At 16, Petzoldt decided to scale the Grand Teton with a friend. Between them, they had a map. Setting out in blue jeans and cowboy boots, they surmounted hypothermia, fatigue and hunger on the three-day climb.

Romantically speaking, they summited the Grand. In reality, the peak nearly claimed their lives. “It was awful,” Petzoldt said years later. “We did everything wrong.”

Returning home, Petzoldt threw the proverbial pebble in the pond, causing ripples that are still stirring new waters. Because of his peril-filled 1924 ascent, today over 50,000 people worldwide have been schooled by NOLS in backcountry recreation and wilderness conservation and leadership. Techniques Petzoldt devised, such as the “sliding middleman” and voice signal system for climbers, are still in use today.

Petzoldt knew adventure as a route to self-discovery and the reanimation of the soul, and he wanted to make outdoor travel safe. He wanted to guide people into the mountains, and he was determined “to train leaders capable of conducting all-round wilderness programs in a safe and rewarding manner.”

His goals were indistinguishable from his joie de vivre, his philosophy of life, his orientation towards service and his wilderness ethic. To attain them, he refined his own skills until he could develop support for the vision he pioneered. Creatively, he stood on the cusp of environmental awareness, anticipating the people, organizations and inventions that would change the face of outdoor recreation. He provided benchmarks for those who followed.

Petzoldt understood the magical synthesis of sweat and the sublime found in nature’s challenges. In defining sublime, Webster’s dictionary credits scenes in nature with, “Striking the mind with a sense of grandeur or power…awakening awe, veneration, or exalted feeling…” A few pages later it explains that by “sweating out” a difficult situation, man learns to “exert oneself to the utmost…to endure through to the end.” Petzoldt experienced nature’s heart stopping beauty and its risks. Embracing the renewal he found in each offered him confidence and a lifetime with more than the average number of defining moments.

Petzoldt made a series of ascents in the Alps, including a one-day double traverse of the Matterhorn. In 1938 he was selected for the first American expedition to K2 in the Himalaya. During World War II he taught mountain evacuation and cold-weather dress to the ski troops of the 10th Mountain Division at Camp Hale, Colorado. In 1963 he helped bring the first Outward Bound School from England to Colorado and testified before Congress in support of the Wilderness Act.

After four decades of guiding the mountains, the 54-year old Petzoldt tacked a sign to the front of a mountain cabin near Lander, Wyoming. The sign read, “The National Outdoor Leadership School,” America’s first school set up specifically to instruct wilderness educators.

Tom Warren was a high school senior in Riverton, Wyoming, in 1965. His psychology teacher Normal Dixon introduced him to his friend Paul Petzoldt, who gave Warren a scholarship to attend NOLS’ first class. Warren’s $300 leg-up later funded Petzoldt’s famous revolving scholarship fund. Over the years many young people would attend NOLS agreeing to “pay back when able,” a pact that as alumni they would someday enable another student to experience NOLS.

“The course was amazing,” Warren recalls. “We trained for two weeks, running, swimming, rope climbing. We practiced knife throwing and bowmanship. We studied map reading, cooking, camping, first aid, and the flora and fauna.”

After learning the basics, the students spent 35 days climbing in the mountains, during which time they rescued one of their own. The action and adventure impressed 17-year-old Warren, as did Petzoldt the man.

“He always cared for the slowest one there,” Warren says. “He was fair and generous with everyone. He made sure that everything any of us had was shared. If you pulled a candy bar from your pocket, you better be cutting it into enough pieces for all.

“Paul taught you to be responsible for yourself and for others, to exercise good judgment, be punctual, and do what you said. And he was dedicated to the environment.”

The school progressed quietly until 1969, when the popular Alcoa Hour broadcast a television documentary about the NOLS experience. When Thirty Days to Survival aired, NOLS grabbed America’s attention. The show fired “a period of almost unmanageable growth” for NOLS, and Warren was ready to help direct its expansion.

The idea of a Teton Valley branch had long been dear to Petzoldt. So in 1971 he sent the trio of Warren, Gene Forsythe and Dave Polito from Lander with how-to books on building a house. They were to construct theschool’s first local facility.

Patrick Petersen lives in one of the original NOLS houses.

“Paul and my dad, Pete, were good friends,” Petersen says. “They had some business together and Dad sometimes did packing and outfitting for Paul. From about ’76 to ’79, Dad would bring me to the house I live in now and there would be about 60 or 80 people staying there.

“At that time they were trucking students to trailheads in a cattle truck. I didn’t understand why students would pay thousands to a non-profit to ride in a cattle truck until I took my first NOLS course when I was 13 years old.

“As much as the trip, it was the philosophy behind it. Paul was a catalyst for preserving diminishing resources back when minimum impact meant throwing your beer cans behind a bush. Globally NOLS sets the standard for schools of its sort.” Today Petersen guides for Jackson Hole Mountain Guides.

During their second year in the valley, Warren and Forsythe set up winter mountaineering courses. The U.S. Forest Service was increasing regulations and restricting the number of people allowed into the Wind River Range, so NOLS began bussing students from Lander for winter trips into the Big Hole Mountains. From 1974 to 1976, NOLS ran the ski touring operating at Grand Targhee. During the summer the staff taught rock climbing in Teton Canyon. Petzoldt often led excursions himself, and for 10 years he guided climbs up the Grand on New Year’s Eve.

By the mid-1970s, the NOLS board of directors was focusing on the rapid growth in Lander and in the branches based in Mexico, East Africa, Alaska and the Pacific Northwest. Because of mutual disenchantment between Petzoldt and the board, Petzoldt took a much-less active role as senior advisor during this time. In the 1980s he became president emeritus of the organization. The Teton Valley branch shut down until 1987, when the base manager Tony Jewell resumed operations. In 1994, after several moves, the local branch settled into the old Darby Church, a substantial brick building that can house up to 30 students.

“Our branch alone had graduated around 1,500 students,” says branch director Ben Hammond. “We teach groups of eight to 12 students with generally a four-to-one student/instructor ratio, although we may increase the number of guides on river trips.

“Last year and this past winter we taught snowboarding to alumni, and this coming season the course will be offered to anyone who is interested.

“NOLS is growing rapidly,” Hammond says. “The school plans to introduce new branches internationally and may add canoeing courses in the Rocky Mountain region.

“Here in the valley, we have had a long-term goal of partnering with the national forest on the Salmon-Challis to survey and control noxious weeks. We are implementing that project this summer by backpacking into the Frank Church Wilderness to begin work.”

The dedication and enthusiasm behind Hammond’s words proves that Petzoldt’s original educational mission and spirit of adventure are intact among today’s capable leaders. NOLS’ progress is sure-footed and surely would be high-fived by its founder.

“Keep doing,” Petzoldt advised his colleagues and students. “You can’t live on memories!… We have to have something that is real adventure, like climbing mountains, like fording wild rivers…like surviving in the wilderness. In order to supply this outdoor adventure, it takes real leaders.”