Pick of the Past

courtesy of Karen Thorton.

It all started with an enigmatic headline in the November 23, 1925 Teton Valley News: “There will be a meeting of Pea Growers at the Court House on Saturday, Nov. 25.” Pea growers? No one grew peas in Teton Valley in 1925.

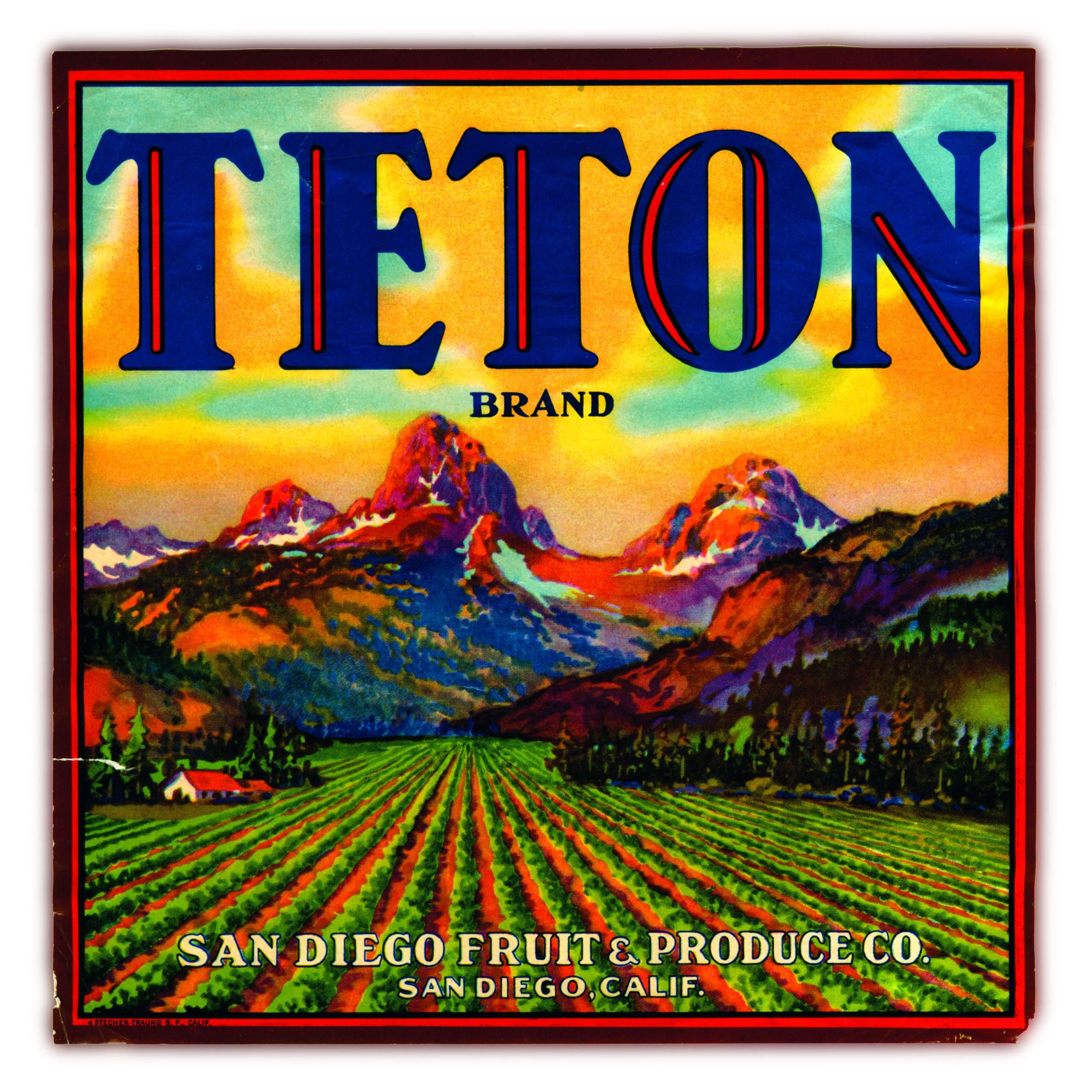

But that was about to change. Financed and developed by the San Diego Fruit & Produce Co. and the conglomerate’s enthusiastic local manager, Glenn Hubbel, a new product blossomed: peas, picked green and shipped fresh. For the next 50 years, August would be pea-picking time in Teton Valley.

Seeking greener pastures and profits, Hubbel spent several years wooing pearaising converts. Wary farmers balked at the idea. Could a profit be made from a crop requiring such skill and intense labor? Teton County agricultural agent A.K. Larsen investigated and concluded peas would work well with the budding seed potato industry, and San Diego Fruit & Produce Co. packed a fat checkbook.

New to Teton Valley, members of the family Fabaceae are among the oldest cultivated plants. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, pea remnants 7,000 years old have turned up in Swiss lake mud. Ancient Greek and Roman writers mention peas often, and green peas graced 12th century nunnery dinner tables in England.

In the valley, peas promised cash in everybody’s pocket. Hubbel deemed peas grown at high altitude superior in quality and flavor to those grown at lower altitudes. Peas not picked for fresh consumption would find a ready market for seed after their maturation and harvest. So the 125 acres of peas planted in the spring of 1926, on T. Ross Wilson’s ranch in Alta, launched the new enterprise.

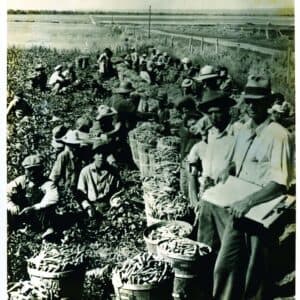

In August of 1926, the call went out for harvesters—who could earn as much as $5 per day. Company trucks hauled pickers to the fields free from anywhere in the valley. Initially, 50 pickers were hired. Soon, another 200 answered the call.

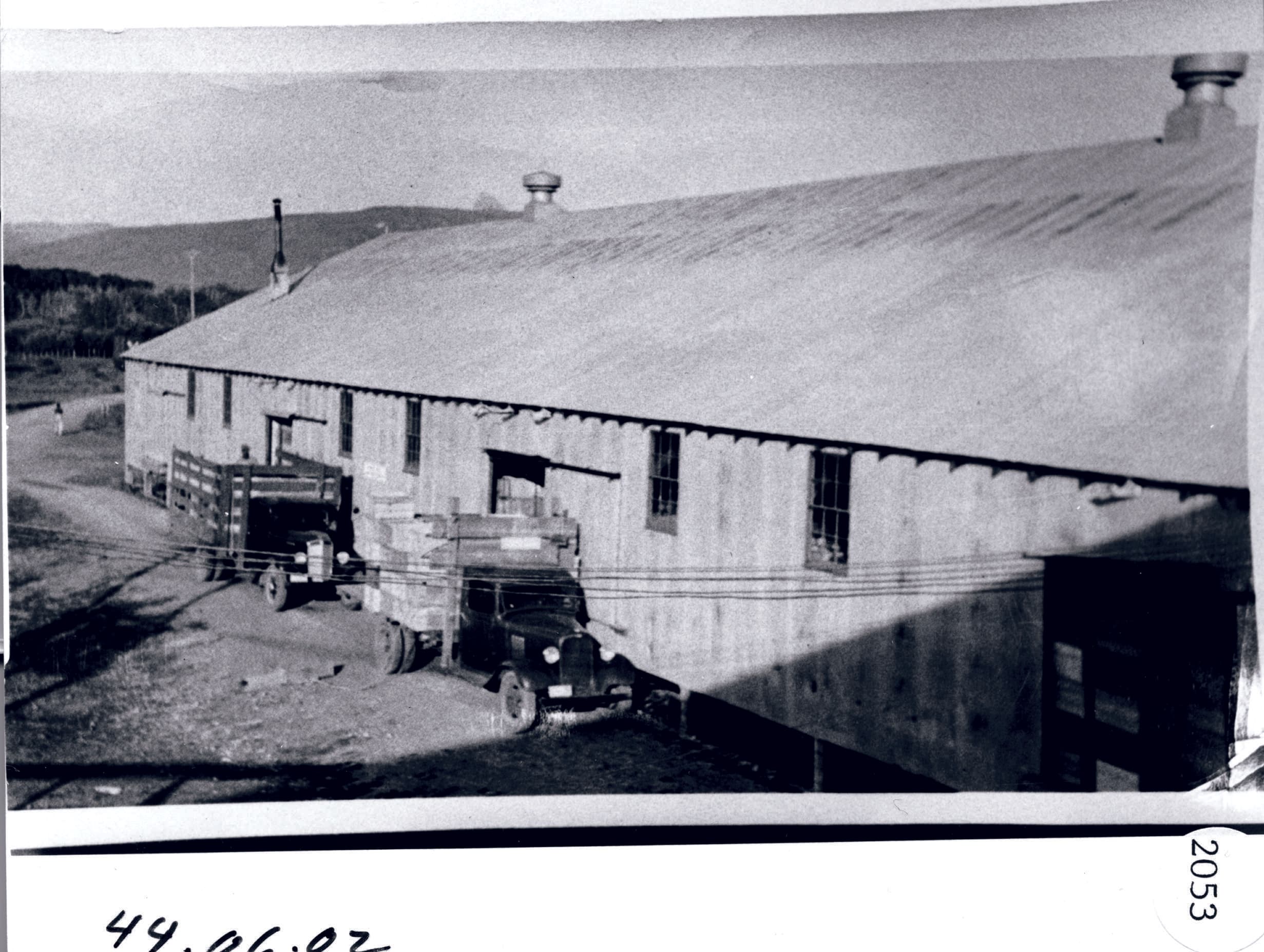

Acreage planted in peas multiplied rapidly. Thirty-nine train-car loads left from the San Diego Fruit & Produce Co. warehouse by the tracks at the foot of Little Avenue the first year. Four hundred workers picked enough peas to fill 150 cars the second year. Within 10 years, more than 350 ice-packed carloads of fresh green peas chugged north out of the valley seasonally. Payrolls mushroomed from $8,000 the first year to $42,000 the second to more than $100,000 the third.

Burgeoning demand drew more than 1,500 pea pickers to the fields each summer, inspiring a 1941 Teton Valley News writer to gleefully ballyhoo: “Picking and shipping will begin on August 1. Companies are expected to be going at top speed, rolling out from 10 to 20 cars of green peas a day, to be shipped to the aristocratic eastern markets. After the first payday, Driggs business will be kept on the jump to meet the demands of the boom this valley will have for the next six weeks.”

Long-time Teton Basin residents recall the days when the valley population more than doubled each summer as Mexicans, Filipinos and Armenian Gypsies settled along valley streams, giving Teton Basin the color and atmosphere of a border boom town.

“The Mexicans and Filipinos camped on Teton Creek just east of Driggs,” says Darbyborn Carol Sorensen, who picked peas in the early 1940s. “Although they were camping, I remember that they boiled their clothes over fires and had very white washes—impressive to me.” Sorensen also remembers lots of fights, usually involving knives and a lot of blood.

Sorensen’s older sister, Maurine Rainey, wrote, “A lot of the pea pickers came from Mexico and lived in willow shacks up on Darby Creek. Filipino pea pickers dressed quite well and stayed in cabins in town; they were quite musical. In the evenings there would be guitar music coming from their quarters and they would play for dances and sing, mimicking Bing Crosby.”

the fields, though, pickers of various nationalities worked together. “I picked peas most of my life side by side with the Mexicans,” Sorensen says. “I drank out of the same milk can [of water] with a longhandled dipper and got trench mouth from it just like everyone else.”

Though it paid well, the work was never easy. “Go outside at about noon on a hot July day,” Sorensen says. “Bend over at the waist. Remain stooped over; inch forward slightly every couple minutes. Do this until several hours have passed. Now, stand up, if you can, and go collect your pay.” Pickers did get one notable perk. “We could eat all the green peas we wanted and get as sick as might be,” Sorensen explains.

“My dad [Virgil Penfold] almost died eating green peas once.” The Teton Springs resort community south of Victor blankets land once owned and farmed by San Diego Fruit & Produce. A large barn used for storing peas still remains.

“We walked over to where the new golf course is [now] to pick peas,” says Ardella Atkinson Berry, who was a teenager in the 1930s and lived near the Victor railroad tracks. “San Diego paid us five cents a basket. Mom and Dad went with me and my sisters, Bonnie, Afton and Maxine, when they could.” Earnings bought school clothes, Ardella says.

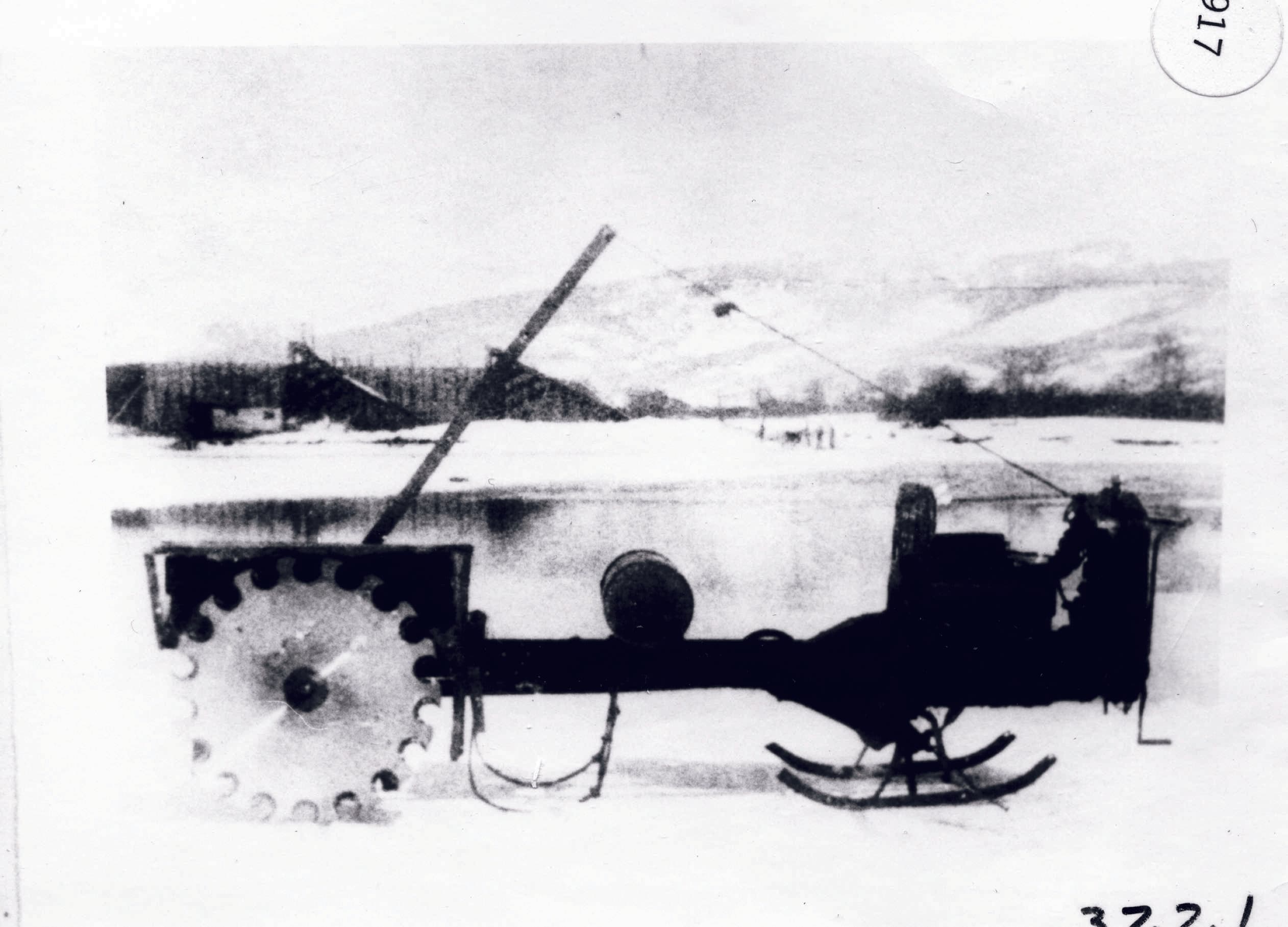

Keenly perishable, peas must be harvested quickly before they pass through the optimum stage of maturity. Starch content increases (and sugar content decreases) as the peas mature, reducing the value. Delaying a day or two in harvesting may result in greater yields but might cause a 90-percent reduction in quality, according to a crop profile developed by the United States Department of Agriculture. Three hundred fifty baskets of peas filled a truck. Two truck loads, or 700 baskets’ worth, filled a train boxcar. Chipped ice, pressure blown into boxcars, ensconced the peas in a frozen cocoon. Long before commercial refrigeration, the process demanded tons of ice—in August. Thus a parallel industry was born.

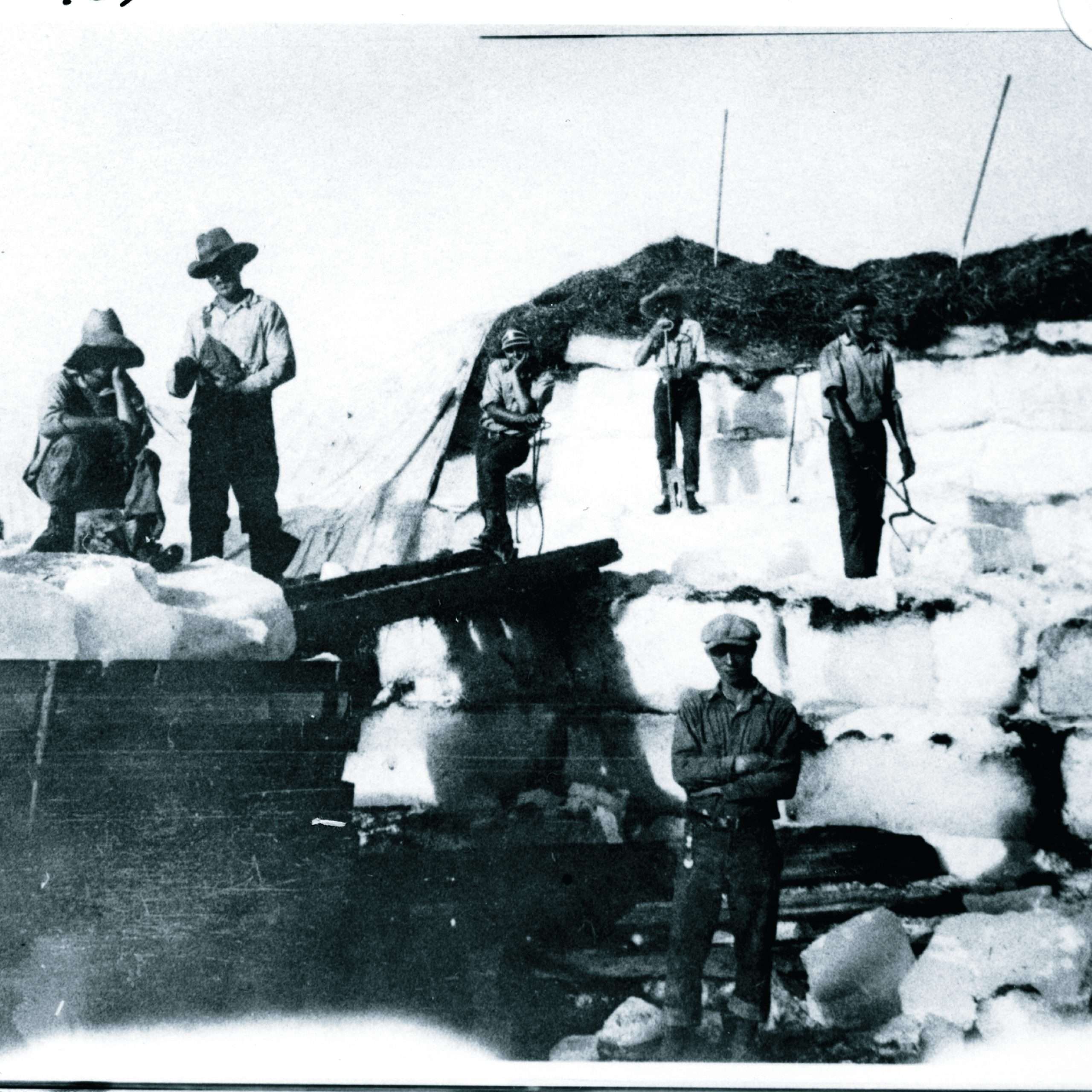

Originally, processors shipped in ice from out below by train, but within a few years, winter ice ponds surfaced. Hillman brothers Wendell and Gheen were the first to see a way to make a few extra bucks by farming ice. By flooding a pit scooped from cold weather arrived. Sweeping the ice free of snow as it fell, they periodically pumped water in to build layers, which they harvested when they were a foot thick. A homemade motorized ice saw expedited the process.

Ice harvesting bumped up the local economy and offered off-season jobs. In a 1973 interview conducted by Idaho historian Harold Forbush, then-81-yearold Jesse Edlefsen explained how it was done. “They would go in there with a saw and they would saw strips so wide and they would crosscut it and make it so long, you see, and then they would saw down about six inches and then you could break the rest very easy, break it off with what they called an ice spogeror, a bar that was tapered just right to go right down in there and break that ice off and it was run into a chute, an ice chute, and then run up into the building and as we got higher kept raising up on the chute.

The building had about four inches of thick walls filled with sawdust and a roof on it at the ceiling, at the top was filled with about two feet of saw dust, and your ice would keep very well.”

The Hillman brothers delivered ice for the 1928 pea harvest, but disaster struck the following summer. “HILLMAN BROS ICE PIT CATCHES FIRE!” announced the August 22, 1929 Teton Valley News. Actually, the storage shed adjacent to the pit burned down. A cigarette carelessly tossed in the straw covering the ice sparked a conflagration that melted 500 tons of ice, a loss of $1,500 for the Hillmans and much more for the San Diego Fruit & Produce Co., which had to import ice.

In the summer of 1935, pea farming turned ugly. In response to wage disputes, Governor C. Ben Ross declared martial law in Teton Valley. Those who rose early on August 15 watched a convoy of 20 National Guard trucks rumble into Driggs at daybreak and pitch camp on the outskirts of town. About 125 soldiers wielding rifles with fixed bayonets leaped down and began patrolling roads and surrounding fields.

The conflict? Pea companies paid pickers 70 cents per hundredweight and an additional 15 cents per hundredweight if the picker stayed with the company throughout the season. Strike leaders demanded a flat $1 per hundredweight. Rita Pérez, born in Idaho Falls in 1930, recalled her brother, Asunción Pérez, telling her that farmers physically abused Mexican workers. In a 1990 interview conducted by Rosa Rodriguez as part of an Idaho oral history project, Rita recounted that knives flashed in retaliation, dispatching farmers to the hospital and Mexicans to jail. Tempers smoldered. Armed farmers threatened to massacre the itinerant workers.

As the tension escalated, farmers feared economic ruin if they lost their pea crop. Vigilantism hung in the air. At one point, 175 farmers gathered at the sheriff ’s office swearing that if they could not get order established by civil authorities they would clean out the Mexican camps themselves.

Sheriff Rex Smith estimated that about 90 percent of the workers—Mexican, Filipino or native—were willing to work at the prevailing rate, but the remaining 10 percent “were keeping these pickers out of the field by threats of violence against themselves and their families.” In addition, “a gang of Mexicans” had intimidated his deputies.

Colonel F. C. Hummel, a National Guard commander, agreed with Sheriff Smith. He alleged that liquor and marijuana circulating among the dissidents added smoke to the fire.

Swiftly, Hummel and his troops entered the labor camps, arresting about 125 identified troublemakers. Another 30 were picked up on the streets of Driggs, along with a few Anglos and what Hummel called “parasites and camp followers.” Held under guard until they were paid owed wages, the lot was then packed into National Guard trucks or forced into their own vehicles and escorted by troopers to the county line, where they were told never to return to Teton County.

Peace returned to the pea fields, but another task awaited martial law. Water rights conflicts had simmered weeks before the pea-picking strike. Teton Valley farmers, facing drought conditions, opened irrigation headgates to turn water into their fields rather than down the river. Downstream farmers in the Rexburg area claimed the water was rightfully theirs due to prior agreements, and that withholding the water threatened a $500,000 beet and potato crop. They appealed to Boise for help.

The governor, the state reclamation commissioner and a judge ordered the gates closed, allowing water to flow to Rexburg farmers. For days, defiant valley farmers, outnumbering state water officials, followed them along the water lines and opened the headgates minutes after they had been closed.

Eventually, gun-toting guardsmen posted at headgates along the main streams quelled farmers’ attempts to divert the water, and tension subsided without violence. A Boise trooper became the only casualty, shooting himself (though not lethally) in the knee while fiddling with a pistol.

Many Teton Valley locals maintained that Governor Ross used the strike as a ruse to close valley headgates with National Guard muscle. “It wasn’t as much the peas as it was the water,” Jesse Edlefsen said, “but they killed two birds with one stone.” Martial law was lifted August 18, 1935, five days after it began.

World War II tripled valley pea production. Encouraged to produce food for victory, farmers planted 2,200 acres in 1942. The bonanza remained robust after the war and into the 1950s. “During the harvesting season Randolph, San Diego and Sawyer employ a small army of workers,” the Teton Valley News reported. The payroll ran generously, stimulating business of all kinds. Much of the pea money stayed in the valley.

In the ’60s, the times changed. More migrants came as family units rather than single men, and as numbers grew, many established permanent residence. Ethnicity flourished, contributing Mexican fiestas, dances, restaurants, businesses and sports to Teton Valley culture.

Fickle variables particular to raising peas eventually decimated the industry in the valley. If it wasn’t a hailstorm hacking up the vines, it was root rot ravaging them from below ground—or a freak freeze killing both vine and root. Take July 12, 1943, for example, when the mercury skidded down to 20 degrees, decimating half percent of the pea crop.“The last year [my husband] Phil and

I raised peas ended our farming career,” Carol Sorensen says. “The Mexicans were to pick them the 30th of August. The night of the 29th it looked like frost, so Phil went out and made smudges [burners which produce thick heavy smoke] to light. About 4 a.m. he went out to light the smudges and saw a glisten of ice over the field—our one cash crop was gone! We dropped farming and went to school.”

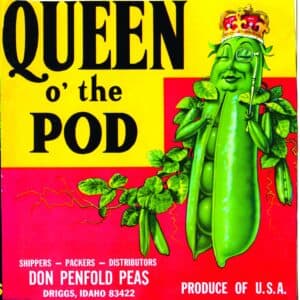

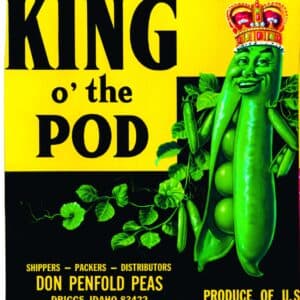

Other farmers followed the Sorensens’ example. When San Diego Fruit & Produce Co. pulled out in the late ’60s, Don Penfold became pea baron. Penfold Farms, crop under the brands King o’ the Pod and Queen o’ the Pod. “Peas were a great cash crop for us. It gave us an August payday before the spud harvest,” says Don’s wife, June. “Entire families worked for us. They cooked meals out in the fields. I loved to buy myself a good Mexican lunch.”

“Guys tried lots of different kinds of peas, Alaskans and Perfections, but we had the best luck with Icers,” says Don and June’s son, Paris Penfold. Icer 95, a monstrous pea 10 to 12 inches long, found a market in exotic-produce stores and gourmet restaurants on the East Coast.

Mechanical pea harvesters, which were common elsewhere, never reached Teton Valley. To the end, Penfold Farms hired locals and migrant workers, who were paid immediately in the field as they brought their filled baskets to the paymaster. Janet Field, who married Paris in 1973, remembers carrying scales and a cash box out to the fields. A worker could pick as many or as few baskets as he or she wanted. “We still have a couple of jars of Indian-head nickels left over from those days,” she says. “We used a lot of nickels.”

Penfold Farms would likely be picking peas today had it not been for two things: Cesar Chavez and “refer” cars. “They [Mexicans] would watch Cesar Chavez on TV at night and talk strike the next day,” Paris says. Chavez, an American labor leader and activist, worked to improve wages and working conditions for migrant workers nationwide. “We paid a fair wage,” Paris maintains. “In the ’70s, a hard-working family—and there were many of them—could pick enough peas to buy a new truck and leave town with money in their pocket.”

But the pea industry died when the railroad switched to refrigerated, or “refer,” cars, rendering ice cars obsolete. “Refers were twice as big [as the old cars] and took longer to fill,” Paris says. “We had to pay a fee for the cars sitting on the tracks for days waiting to be filled.” Profit margins slimmed, then vanished.

Predictably, Penfold Farms decided to grow something else. Soon, the railroad went belly up, and the tracks were removed. As years wore on, the right-of-way became a biking path.

Today, only a litany of pea varieties—Perfection, Alaskan, Chang, French June, Oregon Giant, World’s Prize, Well Wood, Bangalia, Gregory, Laxton, Alderman, Lincoln, Little Marvel, Icer—shells out memories of a crop other than potatoes.

Shipped in ice-filled railroad cars, peas created an off-shoot industry to cut ice and store it in sheds and barns, in sawdust, until August.

Pea sheds can still be seen standing around Teton Valley. Photo courtesy of Teton Valley Museum

Brothers Wendell and Gheen Hillman invented a motorized saw for cutting ice to keep peas cold in August.