Shepherd’s Fortune

Before day break, as the sky turned pink and the smell of dew-wet grass mingled with the rich aroma of unfiltered cowboy coffee, Lindsay Hatch rolled out of his bunk. As a sheep-camp jack in the mountains of Teton Valley in the early 1950s, he had to ensure that his uncle Sam Egbert, the herder he accompanied, was ready to move as soon as the sheep were.

When the din of restlessness started bleating through the band, Sam and his dogs would take off to quiet the chaos while Lindsay, an 18-year-old with nothing better to do, either broke down camp and got ready to move on, or organized camp and indulged in his hobbies. These included anything from braiding leather into bridles and belts, to whittling and wildflower photography. Lindsay’s favorite pastime wasn’t quite so genteel, however. Most days he would hop on his horse and ride through the mountains, looking for chances to target practice on rock chuck.

Around 10 a.m. Sam and Lindsay would have a breakfast of hot cakes, eggs and bacon, prepared in the scant cookware they carried, primarily a Dutch oven. The fresh meat and eggs were a bit of a luxury. If those ran out before they met their resupply wagon, they’d be back to the packable rations of corned beef and Spam, canned milk and basics biscuits, and whatever small game they could hunt. When the meal was over, each went on with the day’s work of moving the sheep through the rangeland.

Though the job often required 16-hour days, Lindsay, a valley native, recalls his time as camp jack with fondness. “It was all fun. I love the outdoors. The great thing about that life is that you had your own schedule. I had plenty of [time] to stop and pick a few berries and get a drink of water from a nearby creek.” The only responsibilities demanding his attention were cooking, setting up and taking down the cook tent, and moving the sheep wagon.

He got out of sheepherding a few years later, when he got married. And since his stint, most sheep ranchers in the valley have given it up too. Across the state, the industry’s viability has been waning since 1937, says Stan Boyd, executive director of Idaho Wool Growers Association. Dick Egbert, who at 96 still owns and manages bands of sheep on Teton Canyon grazing allotments, estimates the valley could have hosted as many as 400,000 sheep at one time. But today, statewide sheep counts tally only 250,000 head, according to Boyd.

The shift correlates to the steady reduction of rangeland and the influx of alternative job opportunities, particularly in recreation hubs like Teton Valley. “The cost of raising sheep have changed. They don’t trail’em anymore,” Lindsay says, for example. “They just haul’em.” Despite obvious economic ramifications, traditional herders mourn more the loss of a lifestyle than a livelihood, suggesting the rigors of the mountain range did more to condition the human than the herd.

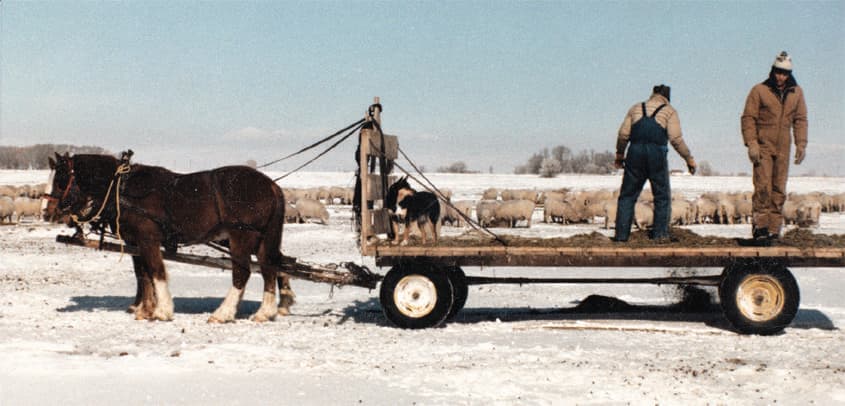

“Sheep were everything,” says Vickie Jorgensen, whose parents and grandparents herded about 9,000 sheep in the valley’s mountains. “I would scamper out of my bed, pull on my dirt-crusty Levis and run out to ride on the apple cart,” a wagon used to move lambs and ewes into lambing sheds in early spring.

Her constant immersion in the working lifestyle earned the animals’ trust. “Sheep rely so much on their senses, other than their eyesight,” she explains, “so they’re really easy to spook. But I would run through them in count them, or climb over them, and they didn’t think anything of it. I smelled like them. “kind of a pungent, musky smell completely separate from the smell of manure.”

Historically, the children of herders apprenticed to the trade. Though Vickie was never a sheepherder herself, her parents were born to sheepherders and continued the tradition. Id didn’t pay a lot, but at a time when domestic wool growers could compete with importers and lamb meat brought a reliable income, herding provided the means to raise a family.

And the mountain pastures always offered something for a child to busy herself with. “We’d trail the band and look for arrowheads in the dust they’d stirred up,” Vickie says. “Or we’d look for cottontail rabbits to keep as pets. There were always a zillion things to explore.” One of six siblings, Vickie eagerly anticipated her turn to trail sheep in the high pastures with her grandparents Melba and Mutt. “We got to go one at a time. One kid was enough to keep track of,” she says, laughing.

The summer rangeland system was complicated. Several bands of about 2,000 sheep spend four months, from late April to mid-September, traveling what’s known as the sheep highway” and roaming the high pastures at its end. This 100-foot-wide route, from the foothills southeast of Rexburg into the Big Hole Mountains, acted as an artery connecting separate parcels of grazing land. The bands staggered themselves, veering off the Forest Service-regulated thoroughfare to browse in designated pastures every day or so. When they reached Elk Creek and Indian Creek, above Palisades Lake, the bands spread out, and the herders communicated their less-frequent moves through the packers who brought supplies.

One of the main challenges of the sheepherder’s job was to make sure the rangeland didn’t get overgrazed. “Sheep are kind of brush-eaters,” Vickie explains, “but it’s not a free-for-all. If you’ve got a good herder and good dogs—who are the real herders, by the way—overgrazing is never a problem.”

At the peak of sheepherding’s profitability in the 1950s, as many as 400,000 sheep grazed Teton Valley’s mountains each summer.