Teton Valley News

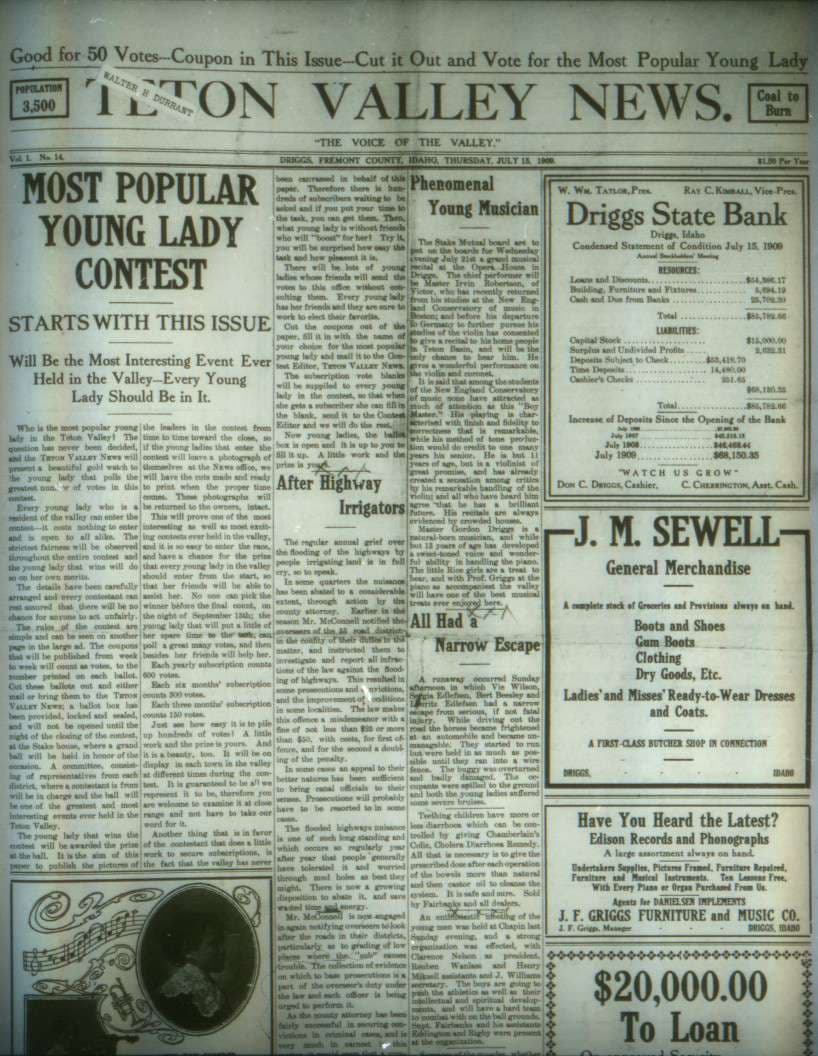

On April 15, 1909, James F. Blumer tightened the quoins, locked the chase, rolled on the ink, pulled the large lever, and printed Volume 1, Number 1 of the Teton Valley News. For almost a hundred years henceforth, “The Voice of the Valley” has offered a weekly snapshot of daily life on the Idaho side of the Tetons.

Blumer, self-appointed defender of community values, aimed his paper at what he considered the town’s den of iniquity. “The pool hall is the twin brother to the saloon and the saloon is in league with the devil, and the devil is ruination of mankind.” He promoted a petition for citizens to choose between “wet” or “dry.”

“It is safe to say that the saloon will receive such a blow at this election it will never more trouble the good people of this district,” Blumer wrote. In Driggs, the 143 to 11 vote was so dry that he called it “dusty.”

Driggs saloon and pool-hall proprietor Ed Hammond seethed. His threats against Blumer and the newspaper resulted in an arrest and a $250 fine. “Any time anyone thinks they can muzzle the Teton Valley News, by threats, when the question is of right, that party makes a mistake, because we positively refuse to be muzzled,” Blumer wrote.

Things escalated. Hammond’s father, Ben, was Blumer’s landlord. Hammond sent Blumer a nasty letter demanding overdue rent on his father’s behalf. “He is so ignorant he does not know he has laid himself liable to U.S. Postal authorities by sending threatening letters,” Blumer wrote. “A man will tolerate the barking of a cur at his heels just so long then something will happen. So if this pup has any friends, they had better chain him up.”

BLIND PIG IS NO MORE—Was Forced to Leave Town crowed September 1909 Blumer headline. Cutting a deal with the district attorney, Ed Hammond agreed to leave town in lieu of charges of selling whiskey to a minor and selling liquor without a license. Blumer took credit for closing the pool hall and hounding the owner out of town. “The entire Hammond outfit pulled out of Driggs Wednesday afternoon bound for Twin Falls. Thus endeth the first lesson.”

Lesson two? Shop local. Told by a subscriber she could get butter wrappers from mail order for two dollars per thousand, Blumer editorially retorted, “Now right here is where we have a kick coming. The News was established for the Teton Valley for the purpose of filling a long-felt want, to boost the valley and further the interests of all its inhabitants individually and collectively.

“Mail order fiends” should support home industry even if it costs a little more, Blumer said. Buying locally gave individuals the satisfaction of contributing a “little mite” toward the support of a hometown paper working overtime for their interest and welfare.

Using the editorial “we,” Blumer verbally jabbed and sparred weekly. “We wish to inform readers of the pack of damable [sic] lies published in the Jackson Hole ‘Curio’ which originated in the brain of the lazy shiftless pigheaded slubberdegullion over the hill.” Douglas Rodeback, editor of the Jackson Hole Courier, had accused the Teton Valley News of soliciting subscriptions and selling advertising space in Jackson. Blumer claimed his former employer owed him $38.15 in back wages, to boot.

Editor, owner, and printer all being he, Blumer thought nothing of writing personal opinion “news” stories.

“We see a spirit of jealously between different towns in Teton Valley,” he wrote. Miffed Darby citizens complained of poor coverage for their Fourth of July celebration, while Victor and Driggs people accused Darby of “butting in” on the holiday activities. “We, as “The Voice of the Valley,’ extends an invitation to the towns and wards to ‘kiss and make up’—let bygones be bygones.”

In December 1909, a rocky eight months and thirty-eight issues into his enterprise, James F. Blumer threw in the towel, selling the paper to J.R. Fairbanks and C.G. Campbell. Telling the new owners he was “tired of trying to reform the county,” he left it altogether.

That the Teton Valley News survived while dozens of weekly papers in the Intermountain West failed was largely due to a civic-minded printer-turned-editor named Fritz Carl Madsen. He bought the paper in July 1911 from Fairbanks and Campbell, and for the next three decades used it to extol the valley’s bright future.

Born in Denmark in 1863 and apprenticed to a printer at age fourteen, Madsen landed in New York in 1884, where he learned English working on Danish-American newspapers. Pursuing printing jobs in the West, he turned up in Driggs as a printer of the News briefly in 1910. The next year he bought the paper.

That fall, forty-eight-year-old Madsen married twenty-two-year-old Mabel Pearson. Her name soon appeared as co-publisher/editor. Each week the husband-and-wife staff wrote editorials, edited local news, solicited advertising, gathered news from other sources, set the type, printed the paper, and delivered the printed word about the county.

EVERYBODY IN TETON VALLEY SHOULD SUPPORT THE HOME PAPER headlined Madsen’s first issue. “If the people of the Basin wish a good, live sheet and are willing to come forward and say so with the long green, then we shall attempt to do better and better each week.”

Madsen explained a “live” newspaper added to the prosperity of the county. “We are not speaking for the paper’s sake alone, but the whole county in which we have cast our lot. We want it to prosper; to become more prosperous, we need a larger population, and we cannot get others to locate here unless we make a good showing.”

Optimistic and energetic, Madsen believed Teton Valley was destined to become an important and influential place in the West. To attract new settlers, he often relied on exaggeration without hesitation; after all, the success of his paper depended on the growth of the towns.

Drums for subscriptions and advertising needed beating frequently.

“The better support a paper receives, the more good it can accomplish; cut off an editor’s income and reduce him to a struggle for existence, and however willing he is unable to properly represent your progress,” Madsen wrote in 1912. “The local paper will always be taken as an index to the community it represents; if up-to-date and prosperous, the community will be considered flourishing and progressive.”

Regarding Victor’s lack of support: “To take your patronage to a newspaper sixty miles distant scarcely is the right way to boost your town. It is on par with sending your money to a mail-order house. … Victor should consider starting their own newspaper.”

And on charges of Driggs favoritism: “In the matter of advertising, we get next to nothing from any other town in the valley. The newspaper business, like any other, is a bread-and-butter proposition. It is impossible for us to expend money to gather news from Victor or Tetonia or any other point unless there is an income to warrant such an expense.”

“When things improve we’ll get out a paper worth the price of subscriptions.” Madsen once apologized, citing that lack of revenue and the high cost of materials were responsible for a lack of local news coverage.

Local merchants often bought advertising as charity, recognizing the importance of a local newspaper. They would run the same advertisements week after week. This helped the paper since the ads didn’t have to be re-typeset.

Cajoling, praising, lecturing, haranguing, and contest ploys paid off. Within a year, circulation had doubled.

The linotype machine and precast metal plates, known as boilerplates,” replaced ready print pages, allowing Madsen to expand the paper to eight and occasionally sixteen pages. A huge time saver, boilerplates arrived with text and illustrations ready for printing. Features from around the country and the world provided a cosmopolitan air, and syndicated columns by Walter Winchell, Drew Pearson, Grantland Rice, and Henry Dworshak served up editorial-page content.

Boilerplate material pandered tobacco for Lucky Strike (“It’s Toasted”) and Camel (“I’d Walk a Mile”). Week after week, readers eagerly devoured realized stores like The Story of the Santa Fe Trail. “Just Between You and Me” by Helen Brooks and “Kathleen Norris Says” fed the advice appetite, and the likes of Mutt and Jeff and Lala Palozza brought a full page of weekly chuckles.

Bearing out Horace Greeley’s iron law of journalism—most readers want to see their own names in print, or those of people they know—Tetonia, Sam, Haden, Richvale, Chapin, Bates, Victor, Driggs, Darby, Clementsville, Cedron, Badger (later Felt), Palisades (later Judkins), Cache, Alta, Clawson, and Hunnidale submitted weekly columns. Many readers subscribed for no other reason than to find out what their neighbors were up to.

No item was too trivial for these columns, usually written by someone in the community. For examples:

From Victor: Ed Rice is moving into the pink house Otto Lumbeck has been occupying for the winter. Otto has moved across the street in the white house.

Haden Toots: The Knight boys of Clawson were in town Wednesday buying harnesses.

Tetonia: Mr. A.J. Anderson has left for Rock Springs, Wyo., for the winter. The blizzards are too much for A.J. He says Rock Springs might sound hard, but they are softer than snow banks.”

Over the years, the News detailed a surprising number of violent deaths: drowning in lakes and streams, lightning strikes, avalanches, fires, guns (both accidental and not), war casualties, car wrecks, childbirth, disease. In the wake of each fatal event, a complete recap of the funeral appeared on the front page.

On July 24, 1942, the paper’s headline read: F.C. Madsen, 78, DIES MONDAY AFTER SHORT ILLNESS. Funeral speakers talked of the man’s newspaper and his influence. He had kindled interest in breaking Teton County off from Fremont County, with Driggs the county seat. A vigorous advocate for bringing the railroad into the valley and establishing a hospital. Madsen was the Driggs mayor, on the Teton High School Board for fifteen years, and charter member of the Lion’s Club.

Madsen’s wife, Elsie, and her son-in-law, Vincent Butler, kept the presses rolling for another three years before selling the business to Victor E. Lansberry in September 1944. Landsberry, an outspoken thirty-five-year-old, learned the newspaper business while working on his brother’s paper, the Ashton Herald. Having spent the previous twelve years as a job printer in San Francisco, he jumped at the chance to move his family from Berkeley to Driggs. The Lansberry family, in the Madsen mode, spearheaded the Teton Valley News for the next thirty years.

Editor/publisher Vic relied on wife Ora for editing help, while son Jim ran the press and daughter Joyce folded papers. “The main printing press was big for the time and the paper folding, after printing, seems to take forever,” recalls Bob Fulton, who as an eleven-year-old in the mid-1940s worked at the News as a printer’s devil. Fulton, now seventy-five, in a July 2006 letter to the paper remembered his boss and the linotype: “Vic would run the linotype machine and compose articles as he typed.”

In a room thick with hot metal fumes and ear-shattering noise, Vic sat at the ninety-character keyboard of the gargantuan mechanical metal monster. Keys actuated a mechanism releasing matrices, small pieces of brass in which the characters, or dies, were stamped. The matrices clanked and rattled from the magazine channels, by means of a miniature conveyor belt, into the assembler box to form lines of text.

“The best job,” remembers Fulton, “was casting out in the old shed behind the office with lead melted in the wood-heated round pot. The mats were placed on a flat plate with sideboards and top. Lead was poured into

the rectangular slot.” The molten metal, heated to 550 degrees, flowed from the melting pot into the letter or character molds, and a complete line of type was cast and ready for the press.

The Lansberrys found success combining boilerplate content with what Madsen had earlier labeled “live” coverage. “High School Notes” from both Driggs and Victor gave budding journalists opportunities to brag about their schools. Student grades and individual class standing were published regularly, for all to see where everyone stood academically. (Today, grandma’s and grandpa’s school records can still be examined in back issues.)

Lengthy letters from LDS missionaries, a weekly staple, brought a local perspective of the world to the valley. Front-page faces of young military men reached a peak during World War II, including pictures, of those leaving, being promoted, coming home—and sixteen who didn’t make it home. Three movie theaters, the Paramount in Victor, Orpheum in Driggs, and Rex in Tetonia, plugged weekly features on the back page.

Check into Teton Valley Hospital and people would read about it in the following week’s front-page “Hospital Notes.” Tonsil removal seemed the procedure of choice, followed by blood poisoning, appendectomies, pneumonia, and burns.

His family grown and health failing, in the early ‘70s Lansberry sold the News to Jackson Hole newsman Fred McCabe and moved himself to Soda Springs.

Originally from Pennsylvania, but lately of Cheyenne and seeking a semi-retirement job, sixty-year-old McCabe bought the Jackson Hole Guide in 1970. That same year he married Elizabeth and put her on as staff photographer, a position she still enjoys today in her nineties for the Jackson Hole News&Guide. A couple of years later, the McCabes bought the Teton Valley News, continuing the tradition of family ownership for another twenty-eight years. “Hardest job I ever had was running a country newspaper,” McCabe often told people, revealing that his semi-retirement strategy obviously didn’t pan out.

J.F. Blumer might not believe the McCabe makeover to his paper, shrinking to 10 ½ by 17 inches and growing to forty-eight pages. Ads disappeared from the front page. Comics, train schedules, syndicated columns, serialized stories, and national news were scrap heaped with the boilerplates they came on, victims of technology and a media-rich world. The lumbering linotype, bottles of glue from cut-and-paste days, and the greasy press followed them to the dump in the early ‘80s. Word-processing computer and digital printers cranked out copy, which rode over the pass to be printed in Jackson.

Eighty-seven years of family ownership of the paper ended with McCabe’s death in 1997 and Elizabeth’s subsequent selling of the paper. It changed hands again in 2001 and yet again in January 2006, when Pioneer Newspapers, Inc., owners of a number of weekly and daily papers in five western states, became the owners. Today, the News goes out below for printing in Preston, Idaho.

“We venture to say there will always be a Teton Valley News as long as there is a Teton County and a Teton Valley in Idaho,” F.C. Madsen prophetically announced in 1923.

More effective than elegant during most of its life, the Basin’s only long-running newspaper has been a major unifying element in the development of Teton Valley. It was, and remains, a plumb line regularly touching nearly every county resident’s life. The yellowed papers of tattered surviving copies, like a reverse time machine, furnish intriguing insights into Teton Valley’s romantic past. The events are gone forever, but the newspaper carries evidence of lives well lived.