Teton Valley’s Checkered Past

It must have been a tough day for Deputy Sheriff Ed Winn back in January 1883.

He traveled some 300 miles on horseback from Malad to Teton Basin, accompanied by his neighbor Bob Tarter. They forded rivers with no bridges and crossed valleys with few trails to see about a murder in a cabin on Badger Creek.

They found the body of the victim, Robert Cooper, with a gunshot to his forehead. Unfortunately for Winn, winter temperatures had frozen the body like a rock. He had to figure some way to get the evidence back to Malad on horseback.

He got an ax cut Cooper’s head off and carried it in a sack tied to one of the horse’s saddles. Local legend has it that on the return journey, the two men stopped in a saloon and ordered three whiskeys. When the bartender asked who the third whiskey was for, Winn pulled Cooper’s head out of the bag and plopped it on the bar.

Winn’s efforts were in vain, however, as the two men accused of the murder were acquitted on a plea of self-defense, there being no direct evidence or witnesses against them. But they were later found guilty of larceny for stealing 40 horses from a ranch in Dillon, Montana, and sentenced to the penitentiary for 14 years.

Such was a fraction of life in Teton Valley before the turn of the century. When the first settlers were moving in during the 1880s, the nearest post office was in Rexburg. The nearest railroad stop was 75 horse-and-wagon miles away at Market Lake, the town known today as Roberts. Teton Valley was included in Bannock County; the county seat was over 100 miles away in Blackfoot. All these factors meant those living in Teton Basin were, essentially, on their own.

While the West was being settled, Teton Valley became known as a rendezvous for horse thieves, according to B.W. Driggs in the book History of Teton Valley. He notes that even as early as Civil War times, horses were being stolen from the soldiers at Fort Hall. The thieves made for the seclusion of Pierre’s Hole. The Valley’s isolation and proximity to the plentiful cattle and horse herds of the Upper Snake River Valley and Montana made it a perfect place to hide as an outlaw and move stolen cargo to the railroads of Wyoming and Utah. Says Driggs, “It is no wonder then that this (Valley) was a velvety path for horse thieves and outlaws of those days with no organization that could attempt to enforce the laws from such a distance.”

One person who realized this rather quickly was Hiram C. Lapham, his family credited with being the first to settle in Teton Valley.

According to Driggs, Lapham soon discovered it was not a safe place to be with cattle. For this reason, he decided to leave in 1887, but “when making ready to go, he found his stock missing.” After searching for several weeks, he found his cows hidden in a gulch in the vicinity south of Leigh Creek. He also found a bunch of stolen horses hidden up one of the Twin Creek gulches in the Big Holes. Waiting in the brush one day, Lapham spotted the thieves going up the creek to check on their loot.

Lapham rode his horse to Eagle Rock (today’s Idaho Falls) looking for a sheriff to help with the arrest of the rustlers. When he couldn’t find one, he rode to Rexburg and found deputy Sam Jones. Together they gathered a posse of three other men and rode all night back to the Valley. They arrived at Lapham’s house at four o’clock in the morning, ate breakfast, and then went in search of the thieves. When they surrounded the cabin, located by the Cache bridge, one of the bandits, Jim Robinson, was shot in the hip. He died a few days later.

The other two bandits, Lum Nickerson and Ed Harrington, also known as Ed Trafton, were held in jail in Blackfoot. They escaped when Nickerson’s wife brought a pistol into the jail hidden in her baby’s clothing, which the prisoners used to persuade jailer Bill High to release them. It was only after bragging to a local farmer about their deeds that a posse formed on their trail. They found themselves back in jail where Nickerson was sentenced to six months while Harrington received a sentence of 25 years. He only served three before he was pardoned.

Harrington returned to Teton Valley to find a new and growing community of Mormons. By now he had acquired quite a bit of notoriety, yet he still managed to find a respectable job as the mail carrier. He was, in fact, the first official mail carrier for the U.S. Postal Service in Teton Basin. This did not prevent him, however, from continuing with his bad habits.

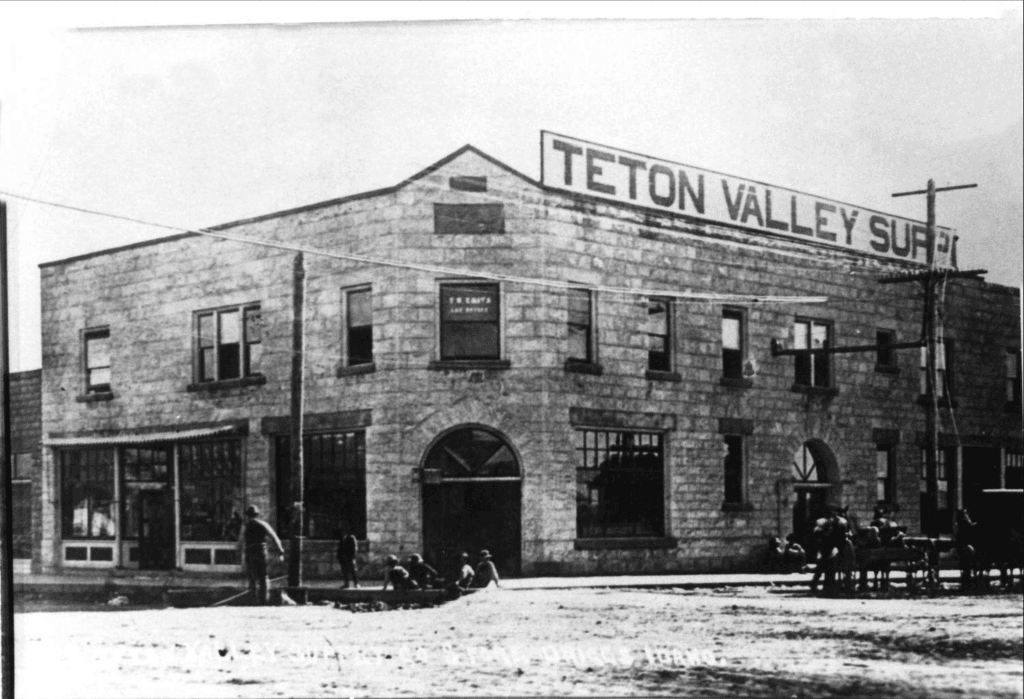

Harrington is honored with being the suspected robber of one of the first stores in the Valley, the Supply House, which was located in Driggs just south of the present-day drug store. With a light snowfall on the ground, the horses used in the robbery could be tracked, especially since one had a crooked foot. All prints led to Lum Nickerson’s place where Teton Creek runs into the Teton River, but the goods were not there. They were probably sent down the river on a raft, never to be seen again, speculates B.W. Driggs in History of Teton Valley. The lack of evidence let Harrington off the hook.

This was just one of several successful robberies Harrington undertook. He loved to rob the stores of the Upper Valley, securing himself an alibi before leaving Teton Valley in the middle of the night. The law caught up with him in 1901, and, according to Eugene Leo Cowan in his excerpt on Harrington in the Snake River Echoes, he spent two years in prison on charges of grand larceny. Yet “doing time” did not convince him to change his ways.

By now Yellowstone had been christened America’s first national park and well-to-do tourists from the East were flocking to see its many wonderful features. They traveled by rail to places like St. Anthony, where a stagecoach would pick them up for a tour through the park.

It was August 1908 when nine stage coaches were robbed somewhere between Old Faithful and Yellowstone Lake. It was estimated that the robber made off with $1,400 in cash and $700 worth of jewelry and watches. No one was ever indicted but Harrington, more commonly known by the name of Trafton during this period, was the main suspect, especially since he would brag of his exploits and show off the jewelry he acquired. According to Cowan, who corresponded with a relative of Trafton’s, the relative remembers “a large, glass-headed doll, and (being) told never to let anyone touch it because they would steal it…when it opened, this doll was full of expensive jewelry.”

On July 29, 1914, Trafton pulled off a similar feat, this time robbing 19 stages all by himself. This earned him the nickname “The Lone Highwayman of Yellowstone.” According to several different accounts, Trafton was a pleasant robber, asking folks to “please” put all their money and jewelry in his bag and even posing for pictures at the scene of the crime. Indeed, many have referred to him as a nice, polite, well-spoken man who unfortunately made his living as a thief.

Ed Trafton will probably go down in history as Teton Valley’s most famous outlaw. Yet for all of his scandalous escapades, he never took anyone’s life. That was left to some other Valley residents.

Fred Sinclair was one of the first people buried in the Victor Cemetery, according to Wendell C. Gillette in his article “A Regrettable Happening” in the Snake River Echoes. Sinclair met this unfortunate demise at the first saloon in the Valley located in Victor and started up by William Raum in about 1890.

The year was 1902 and the railroad had not yet arrived in the Valley. Raum’s retail supplies therefore had to be brought in from Market Lake via horse and wagon. This journey was probably always a source of stress for Raum, leaving him to wonder if his merchandise was going to arrive encased in thick glass bottles or in a puddle at the bottom of the case.

On top of this stress, Raum had a lot of customers who owed him money. He was kind enough to extend credit to those who could not pay. Unfortunately at that time, most of his customers wouldn’t have any money for several months until their stock or crops went to market in the autumn.

These factors may have been eating away at Raum that day when Fred Sinclair walked into his saloon. According to Gillette, Sinclair had quite a large debt and Raum remembered this when Sinclair entered his bar. Sinclair asked for a drink and it may have seemed to him as if Raum did not hear him because he did not get served. Raum, however, was probably thinking about how much money Sinclair owed him and decided not to serve him until he paid up. However, no words were spoken and Raum continued to ignore Sinclair.

According to Gillette, when Raum moved down the bar, Sinclair stepped behind it to pour himself a drink. “Raum, being very much upset by this freedom of privilege, without thinking, picked up a heavy quart bottle, and turned to rap Sinclair with it someplace on his body, which would let him know he had done the wrong act, but alas! Sinclair had turned back toward the bar with the bottle he had picked up, and when Raum swung the bottle he had picked up by the neck, it struck Sinclair just above the right ear in the temple.”

Sinclair fell unconscious and was declared dead when the doctors arrived to check on him. B.W. Driggs notes that Raum was convicted and sent to the penitentiary for a “term of years” but was later pardoned. Lum Nickerson took over the business and found himself with some competition when another saloon opened in the Jones Hotel in Victor.

Another murder took place north of Victor at Darby. On July 5, 1911, a fellow by the name of Ellington Smith shot David S. Neal as Neal was out working in the field. Smith allegedly was angry at Neal for using water Smith felt belonged to him. According to local historian Dale Breckenridge, other things agitated Smith as well.

“Neal had a horse with a running sore that didn’t heal, like a boil, and he washed his horse off in the ditch,” Breckenridge recounts. In those days, everyone got their drinking water from the ditch, he explains.

Smith was sent to the state penitentiary in Boise for life for deliberately killing the man. He died after serving 10 years.

Just a month before Neal’s death, a saloon in Monida, Montana, had been robbed by Charles and Hugh Whitney, who killed three people in the process. According to Patricia Lyn Scott in her book The Hub of Eastern Idaho, they rode south towards Rigby and crossed the Menan bridge. A hundred men with bloodhounds stalked the area around Rigby looking for them but found no signs. For years rumors of the outlaws’ whereabouts circulated, but the men never surfaced. It wasn’t until 1950 that Hugh Whitney revealed that he had been living in Teton Valley since 1911. Even after the turn of the century, the Valley was still a great place to hide out.

Yet life in eastern Idaho was changing quite a bit. Tetonia, Haden, Victor and Driggs had all been dedicated as townsites. Teton Valley News, in the first issue in 1909, reported that there were 3,500 law abiding citizens in the Valley. In 1911, Teton Valley Telephone Company was incorporated. By 1912, Valley citizens were using electricity generated in Teton Canyon by the Teton Valley Power and Milling Company. A water system had been installed from a spring at the mouth of Teton Canyon and piped to Driggs.

Perhaps the biggest change of all came when the Oregon Short Line laid its tracks to Driggs in 1912. No longer was the Valley as isolated as it once had been. Mail could now be delivered by rail and goods shipped in and out more quickly. According to B.W. Driggs, a “general condition of prosperity followed in its wake.” Modern buildings were constructed and new businesses followed as more people made their way into the Valley. By 1919 there were over 60 businesses in Driggs, including an amusement hall owned by E. Beesley, a billiard hall owned by George Griggs and several hotels. The population in some eastern Idaho towns more than doubled between 1910 and 1920.

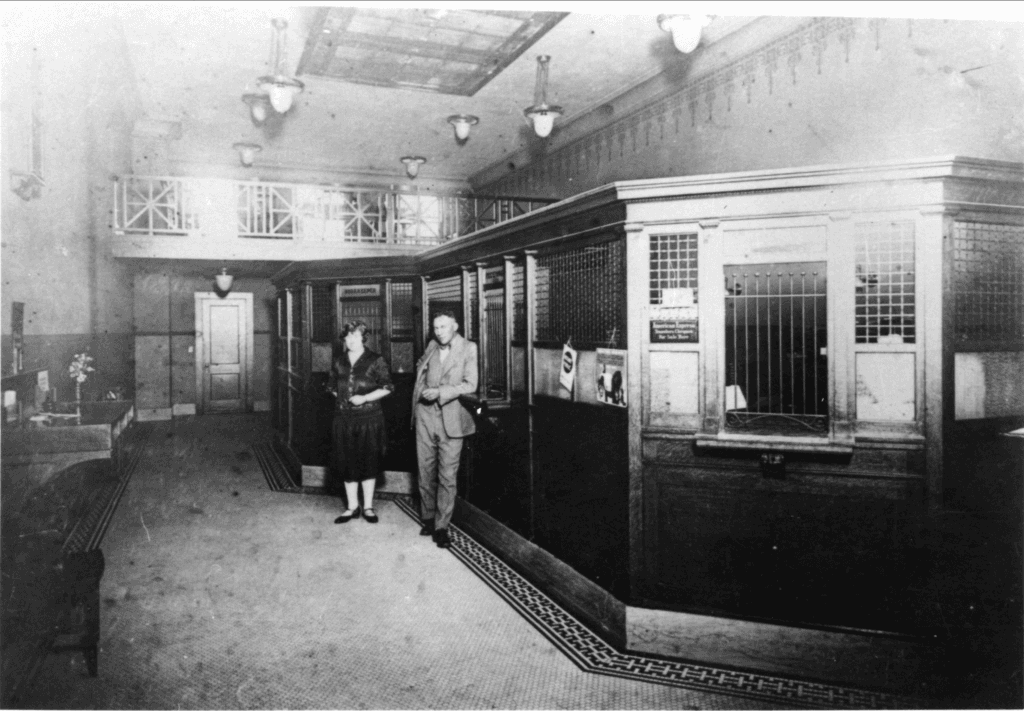

Victor was one of the towns that was growing at this time, with merchandise stores, hotels, dance halls, saloons and even a bank. This bank was the site of a robbery in 1921.

It was February 19, reported the St. Anthony Teton Peak Chronicle, at about one o’clock in the afternoon when Delos Lauritzen, the assistant cashier, was in the Victor State Bank alone. The robber entered the bank, pointed a gun at him and demanded currency and bonds. Only $300 in cash was in the bank as all the bonds were in the Federal Reserve.

The thief took the money and left the bank after putting Lauritzen in the vault. But the thief failed to lock the door. The employee quickly grabbed a rifle and ran to the street looking for him.

Lauritzen turned down an alley, according to the Chronicle, and saw a man. When the bank employee asked the man if he had seen the thief, the reply came in the voice of the robber. The man claimed his innocence but the money was found on him. The article stated, “Liquor seemed to play a large part in bringing out the worst in people,” as the young fellow who committed the crime had been held “in the highest respect of the people of the community.”

Alcoholic beverage consumption in Teton Valley can be traced to the days of the fur trappers’ rendezvous in 1832, the earliest days of debauchery and wildness in the basin. According to B.W. Driggs, at the mountain man rendezvous, alcohol was the first thing in demand, followed by “sprees and feats of horsemanship and personal exhibits of strength before a motley audience, which of course stimulated their valor.” These fur trappers led quite perilous lives, constantly battling the cold, wild animals, and unfriendly Indians. “When the spring caravan arrived with a few luxuries, especially alcohol, the wild Arabs of the mountains often exhibited fantastic excess.”

The accessibility of liquor changed, however, during the 1920s and early 1930s. After Congress ratified the 18th Amendment, the sale of alcoholic beverages became illegal. Yet as with cattle rustling, horse theft, and petty robbery, just because it was against the law didn’t mean it didn’t happen.

According to Breckenridge, during the Prohibition years there was quite a bit of moonshining in the Valley, “just like the rest of the country.” He says it wasn’t an easy place to live during those times.

“You couldn’t make a living back then…bootlegging whiskey was the only way to turn a buck during the Depression,” says Tetonia farmer Jim Beard.

Breckenridge tells the story that one day Reese Chambers asked Roscoe Reese, “How many bushels of hickory you raise out there anyway?” and Reese replied, “We don’t measure it that way, we measure it by the gallon.”

“One night in Driggs a guy was selling whiskey. The sheriff chased him out of town on the swamp road. When the sheriff caught up to him, he had nothing to arrest him on… he could only gather up the empties!

“Under martial law they had it dry…so if anyone went out below (to Rexburg or Idaho Falls), they were real popular, cause you could buy whiskey or good supplies of liquor. They’d be pretty popular when they’d get back,” Breckenridge continues.

“It was the most wild up in Felt because of the tie hacks and a bunch of southerners that settled some of that…fighting was second nature…nothing serious, though, they did a little bootlegging. They didn’t have a good dance in Felt until they got a fight started!”

In Sam, the little town that grew up around the coal mines in the Big Holes, bootlegged whiskey would surface from time to time. Local legend has it that a man who was thrown outside into the bitter cold one evening after a fight was only able to survive through the night because of all the whiskey in his system.

Stories like that were not uncommon for the time. A fellow by the name of E.A. Young, who managed a “soft-drink” resort in Market Lake, was arrested and spent time in jail for selling liquor. It seems the constable of Market Lake was his partner in crime, helping Young hide the bootleg while the sheriff was snooping around.

In 1930, the Fremont County News reported that fish were acting very peculiar in the Gardiner River and that Yellowstone Park visitors were wondering what it was all about. It seemed some “20 gallons of moonshine of a very poor quality—the kind that would take off a camels’ back—was poured into a stream which led into the Gardiner River. Result: the fish just naturally got ‘soused.’ The liquor was a portion of several cargos confiscated by rangers who grabbed four persons in less than a week.

Also during 1930, the Idaho Falls Post Register told the story of a “drove of chickens, birds, and later a few school boys who became intoxicated on snow balls saturated with moonshine whiskey, which the officers had poured on the snow after a raid.” The officers subsequently dumped that snow into a nearby creek.

Gambling was not unknown in Teton Valley either. An early photo taken in front of the first saloon in Victor shows several men sitting around a table playing cards with poker chips. People who remember when the Knotty Pine in Victor used to be the Log Cabin Bar also remembers people sitting around tables playing solo, frog, pinochle and other card games. According to Brent Michael Holmes in his book Victor, Idaho, saloons, bars and pool halls were all similar places of entertainment that usually featured billiards, card playing and consumption of alcoholic beverages.

Times have changed in the last 100 or so years, yet in some ways, things remain the same. When Sheriff Ed Winn rode into Teton Basin back in 1883, it was largely a hideout for those trying to escape justice. Teton Valley is still a hideout today, but its present inhabitants are more likely fleeing urban sprawl, city crime and the stresses of modern life.