The Avenues of Driggs Tell a Story

What’s in a name? When it comes to some Driggs street names, the answer is a rich reservoir of local history. Walking south from Harper Avenue down Main Street, a person crosses in order Howard, Ashley, and Wallace streets, naming the man whose legacy in land a century ago provided the ground for Driggs’ foundations to be built.

What’s in a name? When it comes to some Driggs street names, the answer is a rich reservoir of local history. Walking south from Harper Avenue down Main Street, a person crosses in order Howard, Ashley, and Wallace streets, naming the man whose legacy in land a century ago provided the ground for Driggs’ foundations to be built.

These three and the other east-west streets striping the original Driggs townsite—Ross, Harper, and Little, which also refer to that man’s relatives—are names most people don’t give a second thought to. Yet they contain clues to a frontier past, evoking memories of pioneers, entrepreneurs, wheeler-dealers, speculators, political movers and shakers, bright futures, and tragic ends.

In the spring of 1889 the few stockmen scattered about the valley watched as a wagon train of enterprising and moneyed Mormons creaked and rattled around the northern point of the Big Hole Mountains, forded the Teton River, and set up shop along Teton Creek at the edge of the swamps. Seeking mail service handier than the post office on Moody Creek near Sugar City, Ben Driggs, one of four Driggs brothers living in the young settlement, petitioned Washington, D.C., to establish a post office. He offered the name Aline (A-leen), which local LDS Church leaders had borrowed from the writings of Washington Irving when organizing and naming a ward for members in the valley.

The Deseret News, meantime, suggested a different name in a June 12, 1889, story extolling the wonders of Teton Valley: “ . . . and on its border [Teton Creek] is located the future town of Pine Arbor which consists of a store, three cabins, a tent, and several covered wagons.” Washington officials scanned the petition, noted the abundance of Driggs family signatures, and dubbed the town Driggs instead; in the spring of 1891 they made

Don Carlos Driggs the first postmaster. Soon after, the main street sprouted businesses and buildings, morphing into Main Street with capital letters.

Knifing north and south, Main Street cleaves Driggs into a western third holding a dearth of dwellings and streets, and an eastern two thirds residentially dense and containing the majority of the city’s streets.

You can credit the Wallace family with this lopsided development, said Nona Thornton, great-granddaughter of Howard Ashley Wallace.

“Henry Wallace, a Salt Lake City business magnate and entrepreneur, enlisted his son, my great-grandfather [Howard], to join an 1889 wagon train bound for Teton Valley,” Thornton said, “aiming to get in on the

ground floor of a budding new community ripe with money-making opportunities. Great grandpa Howard was single, twenty-one years old, and available to make the trip.”

Once in the valley, he filed for a homestead and a desert-land entry on behalf of the Wallace family (see sidebar). Howard lucked out, winning both. Henry Wallace bankrolled the enterprise, while Howard provided

the leg work, locating the land and trekking back to Blackfoot, the county seat, to file claims. (Driggs was in Bannock County at the time. In 1893 it became part of the newly created Fremont County; in 1915 it was named the seat of Teton County when that jurisdiction was created from a portion of Fremont County.)

An 1897 survey of Driggs reveals a sixteen-block town with only Main, First, Second, and Third streets identified, and no named avenues. Then, in 1901, four days before Christmas, Henry and Elen Wallace donated to

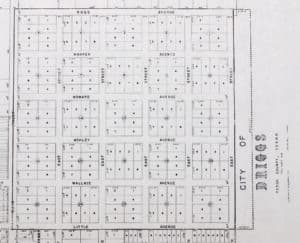

the town of Driggs 160 acres from their desert-land entry, the southeast quarter of section twenty-six. An updated surveymap from 1901 displays twenty-five blocks and all streets named: Main through Fifth streets running north and south and Ross through Little avenues running east and west. The four avenues in the middle read Harper, Howard, Ashley, and Wallace.

Plying a land developer’s prerogative, Howard Wallace had selected family names for the east/west running avenues: Ross for his brother; Harper for his mother’s maiden name; Howard for himself; Ashley, which Thornton believes was named for Howard’s son; Wallace for the entire family; and Little for his wife’s maiden name.

Platted and dedicated, Driggs was now literally on the map. “My grandmother [Howard’s daughter Barbara, born 1911] told us the town’s name would have been changed to Wallace at that time, except there was already

a Wallace, Idaho,” Thornton recalled. A 1933 letter from George H. Wallace, Howard’s brother and another valley pioneer, to niece Claire Wallace corroborates the story. And so does current Driggs mayor Louis B. Christensen, who said, “Driggs owes its existence on the present site to Henry and Elen H. Wallace. The family received recognition for their contribution in the founding of the town when the east/west streets were given family names.”

Locations for a stake tabernacle, stake offices, and a grade school were surveyed. By this time, Howard Wallace had married Margaret “Maggie” Little and hammered up a two-story, lapboardsided house using lumber from the Teton Creek sawmill owned by his father-in-law, George Edwin Little.

“The house, built in 1905, has always been in the family,” said present owner Thornton. “I believe it is the oldest house within the city limits of Driggs still standing. We had a centennial Wallace family reunion in it last July.”

Howard and Maggie Wallace had nine children in the house at 513 Howard Avenue. Some of their kids married into Teton Basin pioneer families with names destined for local prominence—Butler, Buxton, Dalley, and Young—but the family was touched with tragedy. Scarlet fever swept Driggs in 1913, taking five-year-old George Alvin. Daughter Marguerite succumbed to congenital heart problems at age seventeen, and the eldest son, Edwin Ashley, fell from a Salt Lake City trolley car and died from head injuries when he was twenty. Wife Maggie passed away, as well, and in 1924, on the Sunday before Thanksgiving and a month before he would have turned fifty-eight, Howard went down into the basement and took his own life.

Maggie’s maiden name, Little, was another big name in early Teton Valley. George Edwin Little, born in Nauvoo, Illinois, came west as a child with the Utah Mormon migration. In 1862, after serving with the short-lived Pony Express, he married an English girl, Martha Taylor, in Salt Lake City. The next twenty-four years brought the couple fourteen children. After the birth of the last child in 1886, they moved to Teton Valley, setting up the first valley sawmill at the mouth of Teton Canyon. In a financial partnership with Henry Wallace, George began buzzing boards for eager builders.

Martha maintained a travelers’ inn and post office in their Haden home. Energetic and spirited in church duties, she garnered money for a church organ by circulating a petition and sending it to Andrew Carnegie, who ponied up five hundred dollars. Haden Ward had a new source of music.

The couple’s first child, Edwin Sobieski Little (Maggie’s brother), married Zina Wallace (not related to Howard Wallace), in Logan, Utah, in 1886, and two years later he followed his father to Teton Valley. Edwin, Sunday school superintendent of Aline Ward and the first bishop of Haden Ward, served two terms as county commissioner of Fremont County, two years as deputy assessor of Fremont County, and sixteen years as Teton County assessor.

Running for the latter office in 1924, he pitched himself in the paper like this: Ed S. Little —Republican for County Assessor. The man who touches your pocketbook and there is no man in this county more intimately

acquainted with its property values than is Ed Little. The fact Mr. Little has served as assessor practically since the creation of Teton County is the best recommendation that his services are faithful, economical, and efficient.

In 1914, when Thomas R. Wilson and his sons, T. Ross and Clifford, surveyed town streets for sidewalks, the local newspaper advertised one two-room and one three-room house and two adjoining lots on Little Avenue for sale. Five hundred dollars would buy it all. The same year, street crossings of crushed rock placed in the intersections of Wallace Avenue, Little Avenue, and Main Street offered a pedestrian temporary footing—before he or she sunk from sight.

Horse traffic dominated town streets well into the twentieth century. “Driggs is getting to be some lively business burg,” read a 1917 Teton Valley News story. “Saturdays there are not hitching racks enough in town to tie teams to. You will see teams unhitched and tied to sleighs anywhere.”

A walk along dirty, dusty, icy, frozen, mucky, muddy, manured Main Street, depending on the season, took the stroller past: Driggs State Bank (today, the building with a bison on top); J.M. Sewell General Merchandise; Killpack & Winger (“the real estate men”); the Teton Valley News; Walter H. Durrant Photography; the Driggs Hotel (“first-class accommodations at reasonable rates”); J.F. Griggs Furniture and Music Company (“Have you heard the latest Edison Records and Phonographs?”); Ed Hammond Pool Hall and Barber Shop; Driggs Planing Mill; Mame Eddington’s Millinery; and Beesley Brothers’ Livery, Feed, and Stable.

Large bands of sheep passed through Driggs from shearing corrals west of town along what was soon to be called Buxton Road (and was later renamed Bates Road), headed up Little Avenue to summer range in the mountains. “The melting snow is making lower Little Avenue and Main Street look like a lazy man’s stable or barnyard. Some of our citizens have suggested that the Board of Village Trustees send the marshal out with the fire hose and wash the stuff away,” reported the Teton Valley News.

“Lloyd Buxton had a place near the river south of the road across the bridge [Buxton Bridge],” said current resident Farrell Buxton. “When the county ran the road through Lloyd’s property, it became Buxton Road.”

The name Buxton Road didn’t stick. Never its official name, it’s now labeled West Little Avenue to the city limits and Bates Road west of there.

There was a Buxton Street that also didn’t survive the test of time. West off Main Street (opposite Wallace Avenue), block-long Depot Street ends at the former site of the train station (where a 1918 round-trip ticket on

the Oregon Short Line to Salt Lake City would set a traveler back $12.45; Denver, $32.60; Chicago, $67.85). North and south from Depot Street, paralleling long forgotten railroad tracks, runs Front Street—now home to BodyWise Yoga Studio and the recycling bins—formerly known as Buxton Street.

“Whatever got on to any maps [at that time] was not cleared by the city,” said Mayor Christensen; “ . . . the street was part of the railroad right-of-way, which had a trail that the railroad allowed people to drive

on, but there was never a street or avenue . . . Buxton [Street] did not exist then or now.”

“I’m not sure if any of us know why that street was named Buxton,” said Farrell Buxton. “Just as well, since nothing much ever developed along it.”

That’s about to change in a monumental way.

Doing business as Blackfoot Farms, developers plan to build a county court house, a civic center, townhouses, a post office, and retail spaces west of Front Street on five blocks bounded by Ross Avenue on the north and Bates Road on the south. A north/south road will become Driggs’ newest street, with the name Green Street suggested. Whatever it’s called, the street will join Ross, Harper, Howard, Ashley, Wallace, and Little—Teton Valley names forever linked by avenues of asphalt.

DESERT-LAND ENTRIES

United States government land in early Teton Valley, and elsewhere in the West, could be acquired by private citizens in four different ways: homestead entries, timber and stone claims, mining claims, and

desert-land entries. Regarding the final, on the website of the Bureau of Land Management it is written:

“On March 3, 1877, the Desert Land Act was passed by Congress to encourage and promote the economic development of the arid and semiarid public lands of the Western United States. Through the Act, individuals may apply for a desert-land entry to reclaim, irrigate, and cultivate arid and semiarid public lands.”

Because of the time (four years) and money (up to a $1,000 or more) involved, relatively few desert-land entries were awarded in the early days. Henry Wallace was among the fortunate ones, and upon receiving title to this desert-land entry with son Howard’s onsite diligence, he donated 160 acres for the Driggs townsite in 1901. A town, already born, was beginning to mature.