The Grand Question

Towering a mile above the sagebrush valley flats, a bald of granite, the Grand Teton, thrusts like a knife into the Wyoming sky. It’s unlikely anyone has ever viewed this American Matterhorn without wondering what it must be like to stand on the summit of this highest peak in the range.

William Owen wondered. Seven times during the 1890s he tried to climb the Grand. Seven times he failed. Eight summers passed. Once, with the help of his wife, Emma Matilda, and friends, Owen hauled huge iron pegs to within a few hundred feet of the top in an attempt to drive a stairway into the vertical granite cliffs barring the way. It didn’t work. Fueling his frustration was the knowledge that two men, Nathaniel Langford and James Stevenson, who were exploring the region with the Hayden Expedition, reported reaching the summit 26 years earlier. If he couldn’t do it., how could they? Owen was convinced they had lied.

Finally, late in the afternoon of August 11, 1898, the wiry little scrapper of a man, known locally as “Uncle Billy,” stepped onto the 13,770-foot summit, declaring his party the first humans ever to stand there. His claim launched an enigmatic question that has swirled around the Tetons like a tenacious thunderstorm for more than a hundred years: Who climbed it first?

Was it actually Owen? Or had members of the Hayden Expedition reached the summit years before, as they claimed Maybe an anonymous party had scaled the heights even earlier. Or perhaps, as some people believe, Native Americans stood on the peak long before the arrival of white men in the region.

The written history of Teton climbing began in 1872 when the seeds of a long-standing controversy were sown by the Snake River Division of Dr. Ferdinand V. Hayden’s geological expedition.

Captained by 32-year-old James Stevenson, 14 men rode horses into Teton Canyon and turned up the South Fork of Teton Creek, setting up camp in Alaska Basin. At 4:30 a.m. they tossed bacon sandwiches into backpacks and set off to climb “the topmost summit of the loftiest Teton.” As the day wore on, the men wore out. All but two of the climbers gave up. After 18 hours of thrashing through snow, clambering over boulders, fording streams and pulsing themselves up “by climbing to the points and angles of projecting rocks,” Stevenson and Langford wearily plopped down by the campfire, announcing they had “stood on the highest point of the Grand Teton.” Overcoming talus-chocked ravines and gullies jackstrawed with fallen trees, and gaining and losing thousands of feet of elevation was what 40-year-old Langford termed “the severest labor of my life.”

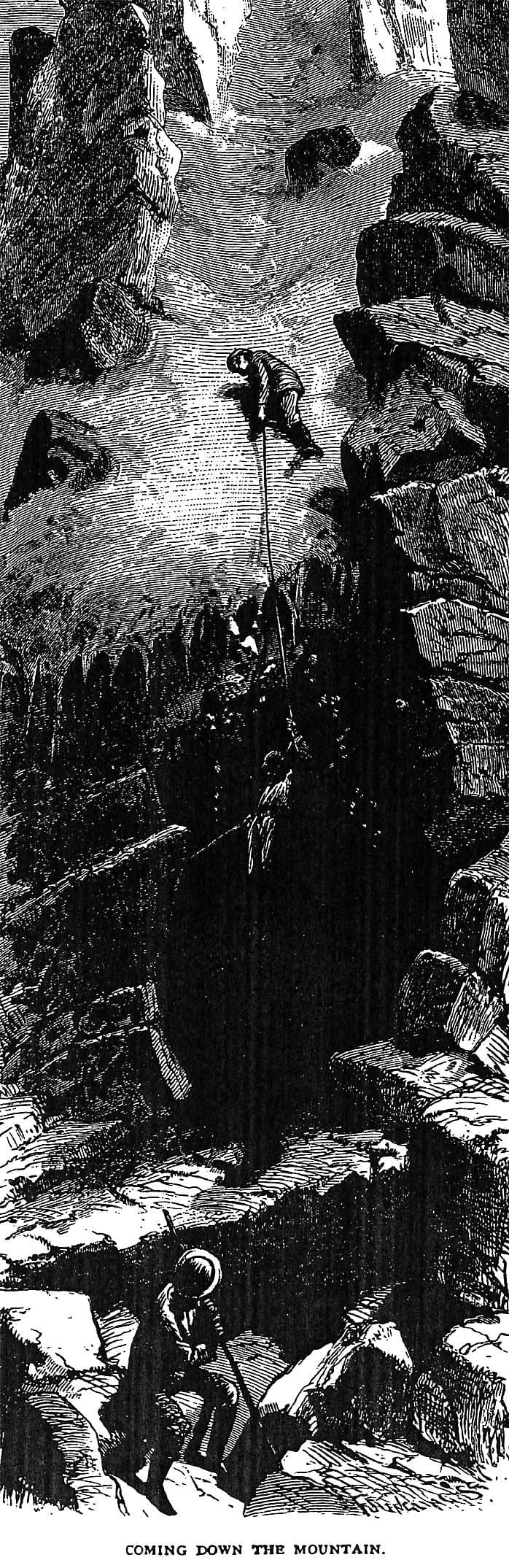

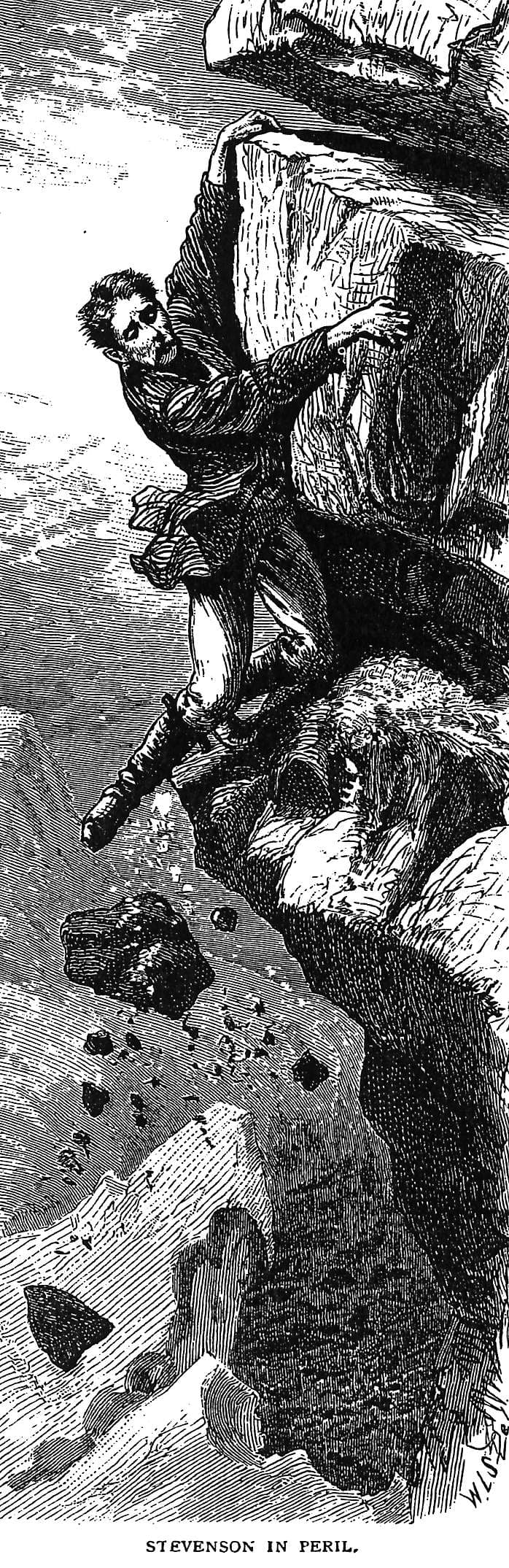

A lengthy account of the feat was published with dramatic and imaginative illustrations in the June 1873 Scribner’s Monthly, entitled “The Ascent of Mount Hayden,” in honor of the expedition leader. The name didn’t stick. The Grand remained the Grand, presiding over the surrounding valleys as they filled with ranchers, outlaws, cowboys, sheep men, soldiers, farmers and tourists on their way to Yellowstone National Park in the last years of the 19th century.

Everyone in Teton country knew the 39-year-old diminutive dynamo William Owen, by his reputation, if not on sight. A Wyoming state auditor and surveyor in the 1890s, he spent summers in Jackson Hole hiking, climbing and riding his bicycle. The fresh mountain air offered respite from the stress of pencil pushing as a government desk jockey in Cheyenne. In 1883 he toured Yellowstone on his bicycle, an “ordinary” with a 5-foot-diameter front wheel, claiming to have been the first person to traverse the park on a bike. Being first was important to him

And the “first” Owen craved most the one that consumed his boundless energy for 30 years, was to be named the pioneer climber of the Grand Teton. It proved a difficult feat. Actually climbing in consumed nearly 10 years of trial and error. Discrediting Stevenson and Langford, two well-known men with national reputations, took three decades.

Owen’s perseverance earned support in 1898, when the newly formed Rocky Mountain club from Denver, hearing of Owen’s fruitless summit attempts offered help in the person of Rev. Franklin S. Spalding, a 35-year-old Princeton graduate who later became Episcopal Missionary Bishop of Utah. Two local ranchers, Frank I. Peterson and John Shived, also joined the effort.

At 5 a.m. on August 11, 1898, the four men left for the summit with 450 feet of rope, ice axes, iron-pointed prods, steel drills and iron pegs. Only the rope would probe to be of any use. Gaining the Upper Saddle easily, they began probing the band of cliffs blocking access to the summit several hundred feet above. Spalding found a narrow ledge along a 3,000-foot precipice just wide enough for a person to wiggle along on his stomach. The thin ledge led to a vertical chimney that took him above the cliffs. Spalding could have achieved the summit first, but he decided to let Owen claim the victory. “I did not wish to go ahead of my party,” Spalding later said, “…so I climbed back down the chimney an hallooed to Owen to come.”

Tossing the rope down to Owen and the others, Spalding hoisted them all up to his perch above the cliffs. The rest of the way to the top was a cakewalk. “We followed a snow ridge for 200 feet and then over the sharp, jagged eruptive rocks, so noticeable above timberline, clambering with a shout to the top. We made it at 4 o’clock exactly. We had been climbing for eleven hours,” Spalding reported, as quoted by author Orrin H. Bonney in his book The Grand Controversy. Immediately, the four men combed the 15-by-30 foot summit for evidence of the 1872 climbers. They claimed they found none. “The most critical, conscientious and thorough search by our entire party failed to reveal the slightest shadow of evidence of a former ascent. Not a stone was turned over no cairn or monument erected, nor could we find any bottle or can of description containing the customary record of ascent,” reported Owen. Was the 1872 claim fraudulent?

Neither Stevenson nor Langford seemed likely to lie, but on that August day Owen charged them with just that (and he spend the next 30 years lobbying for his climbing party—but mostly himself—to be declared first to have scaled the mountain.)

Stevenson, a strong and tireless climber trained as a naturalist and ethnologist, was a loyal and trusted friend of Hayden and accompanied him on several pre- and post-Civil War explorations, fighting in the meantime with the Union Army. He died in 1888.

Langford first journeyed west in 1862, when he mined for gold in Idaho, then settled in Montana. He was named governor of the territory by President Andrew Johnson. As a Montanan he also served on the executive committee of vigilantes that hanged the crooked sheriff Henry Plummer and helped clean up the lawlessness rampant at that time. His book, Vigilante Days and Ways, became a regional classic. Even greater respect and fame came from his efforts to make Yellowstone a national park, including authorship of The Discovery of Yellowstone Park in 1905. His initials, N. P., were often said to stand for “National Park” Langford (his middle name was Pitt). He was selected to be the new reserve’s first superintendent, cementing his unofficial identity as the “father of Yellowstone Park.”

Each armed with his own political clout, Owen and Langford hammered each other in the press for years. The historical curiosity of the argument, amplified by the disputants’ social statures, landed the story in periodicals and newspapers across the country. The controversy quickly heated and then turned malicious.

Owen ignored the premise that gentlemen mountaineers ought to take one another’s word on who makes first ascents. “Five Minutes would have sufficed to erect a suitable monument, which would have completely set at rest all questions as to the first ascent,” he argued. “One stone piled on another would have answered, but event his was not done.” Langford said they had arrived on the summit late in the day, and being exhausted, pressed for time and eager to get down, they did not have time to linger and stack rocks. Besides, as veteran government surveyors, they had climbed hundreds of peaks in the course of their work. First ascents were neither a priority nor unique to them.

Langford mentioned climbing an ice sheet between the Upper Saddle and the cliff above that eventually led to the summit. Owen found no such ice sheet, and it was at this point of the climb that he was repeatedly thwarted during his many summit attempts. However it isn’t unreasonable to assume the ice sheet had melted during the intervening years as noted in The Teton Controversy: Who First Climbed the Grand? By William Bueler.

Still, Owen Found fault with the climbing route and the views from the summit Langford published in Sribner’s. Feeling insult was salting injury, Owen resorted to producing bogus affidavits from his cronies asserting, based on tenuous and convoluted testimony, that Langford and Stevenson had admitted not reading the summit. Spalding in an 1898 letter to Langford, and Bueler in his book both claim Owen likely authored the affidavits himself.

When C.G. Coutant credited Stevenson and Langford with the first ascent in his History of Wyoming and the Far West, Owen lashed out with the charge that Langford had bribed Coutant with $150. Owen offered no solid evidence, but the damage was done. Today there are still those who believe a bribe may have been paid.

To further cloud the issue, an April 3, 1899, letter found hidden among Owen’s papers in 1959 casts a shadow every bit as dark on Owen as he cast upon Langford and Stevenson. Dr. Charles Kieffer, who had been hunting with two other men in the Teton region, wrote to Owen about reaching the top of the Grand on September 10, 1893, six yeas before Owen’s successful climb. The letter included a map of the route with, interestingly, an ice field marked at the same location Langford noted in 1872.

And nine years later, in 1968, another fragment of evidence surfaced. Nineteen-year-old Sidford Hamp, a member of the 1872 party, had kept a diary. Hamp and a companion stopped at the vertical cliff at the Upper Saddle. He reported, “Spender and I stoped [sic] on a ledge and rested whilst the other two [Langford and Stevenson] got to the top.”

In addition to this argument-eroding evidence, both parties overstated the difficulties of climbing the Grand. Each year thousands of people ranging from juniors to geriatrics make the climb via dozens of different routes and variations (granted, climbing gear and techniques have improved dramatically). Uncle Billy insisted the route he climbed was the only possible way to the Grand’s summit. But a few exceptional athletes have actually skied and snowboarded from the pinnacle. And the current record for running from the Lupine Meadow trailhead to the summit and back is under three hours!

Spalding, in a letter to Langford, put the difficulty of the climb in perspective. “I think if you will permit me to say so, you are at fault, as is Mr. Owen, in exaggerating the difficulties of the ascent. If you did not reach the top when you started out to do so, you are a mighty poor mountain climber in my humble judgment; and I cannot understand why Mr. Owen failed so many times before he succeeded.” Spalding also said he didn’t’ care if he was first or thousandth, the climb was worthwhile.

Owen’s 30-year campaign of pleading in the press and twisting arms in the back rooms of the capitol resulted in the back rooms of the capitol resulted in the Wyoming state legislature’s passage of a resolution giving William O. Owen and his three climbing companions credit for the first ascent of the Grand Teton.

In 1929 a heavy bronze plaque was laboriously carried up the vertical walls of the Grand and bolted to a huge boulder on the summit. The plaque, purchased by Spalding’s widow, was intended to lay to rest all the ghosts of prior claims to first ascents of the peak. It didn’t.

For nearly 50 years, the rays of the morning sun flashed bronze as they touched the highest point of the Tetons—and the summit plaque. But it’s gone now. It was reported missing by park rangers on July 1, 1977. The Case Incident Record dismisses the plaque simply as “stolen property,” and it has never been found.

The late Paul Petzoldt, arguably the most outspoken pioneer of American climbing, pointed out that the disappearance of the plaque cracked the issue open again, passing another chapter of the story to another generations of climbers. “I doubt if people who just collect signs and things would go to that much trouble,” he said. “But them who knows?”

And who cares? With Owen’s ascent on the books and all those involved long gone, the Grand question has lost its competitive edge and become steeped in local lore.

Perhaps personal opinion, the saucy arbiter of history, is really where the story starts.

Petzoldt, for one, spoke for those who have lived around the Grand most of their lives. “Hell, they [Stevenson and Langford] never got up there,” he said. “They knew Billy was the first one …”

In that light, underdog Billy Owen was a regional hero for taking on the monolithic bureaucracy of the U.S. Government. The Hayden Expedition of 1872 is a significant chapter in the history of western exploration, and Owen’s insinuation that a lie was published in the official report (by men assumed to be honest) casts doubt on both the survey’s authority and its members’ integrity.

Petzoldt explained the David-and-Goliath details: “Here was the superintendent of Yellowstone National Park and the head of …the Geodesic Survey, being called liars by some pipsqueak out in Wyoming that nobody ever heard of, but having the guts to put it in the New York Herald that he was the first to climb the Grand Teton. Well, those guys [Stevenson and Langford] couldn’t back down. It was already in the report.”

Perhaps Stevenson and Langford fabricated the story of their successes to draw attention to the 1872 survey, thus lending authenticity and prestige to their efforts, On the other hand, maybe Owen’s fervor for the firsts caused him to forsake a few hard facts.

Maybe, in the Western tradition of telling tales as tall as the mountains and as colorful as sunsets, they were all simply following in the footsteps of the Teton region’s enthusiastic first explorers and early cowboys, whose stories swelled to legendary proportions as they traveled back East. Let the “official” evidence, culled from printed sources spanning more than a century, stay in the 2-inch binder locked in the steel-cabinet archives of Yellowstone National Park. After all, questions with definitive answers cease to be grand.

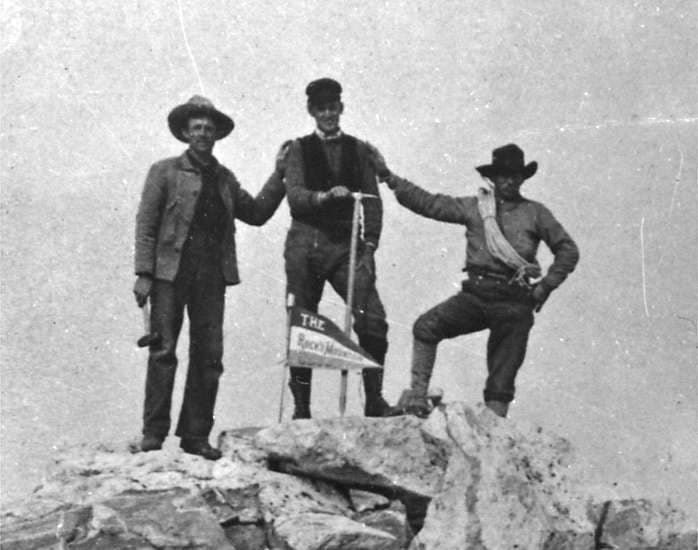

Photo Caption: Careful to document his own successful climb on August 11, 1898, William Owen snapped a photo of fellow climbers Frank Peterson, Franklin Spalding and John Shive on the Grand’s summit. With hard proof in hand, Owen declared his party the first to achieve the ascent, a claim that would be hotly debated for many years.

Photo Caption: Stevenson and Langford reported climbing to the summit over huge ice fields, like the one on which fellow climber Mr. Hamp nearly lost his life. Owen who made it to the summit in 1898, didn’t find ice fields in the locations noted by the members of the Hayden Expedition. Owen used this “evidence” to substantiate his claim that Stevenson and Langford had fabricated the story of their ascent.