Those Were the Days

“Git your little sage hens ready! Trot ’em out upon the floor! Tune up there you cusses! Steady! Lively now,—one couple more. Shorty, shed that old sombrero! Bronco, douse that cigarette! Stop that cussin,’ Cassinero! ’Fore the ladies—now all set.”

The opening lines of the Badger Quadrille, set in 2/4 time, follow a frisky fiddle melding with the melody of a wheezing accordion. Spilling into the darkened dirt street outside the Badger Opera House, the dance music calls for couples to swing heel and toe, spin, whirl, promenade, and stomp until dust bellows from the plank floor, slickened for fancy

dancing with scattered oatmeal. Chairs turn to the wall-held mounds of coats and quilts—the nests of sleeping children. As the hour grows late, turns the corner at midnight, and becomes early, the residents of Badger dance on and on…until morning sunlight splashes the floor.

Sashay back in time to the era when rag-top cars with wooden-spoke wheels, bouncing horse buggies, and sleighs fitted with canvas covers and coal-burning stoves ferried Teton Valley residents young and old to dance floors nearly every night of the year—to Badger (renamed Felt in 1911) and beyond.

In addition to supporting local musicians, the valley’s dance halls and pavilions built community by providing common ground for a common interest, right up to the birth of rock ’n’ roll.

Smith’s Auto Court, an outdoor dance floor on Teton Creek, opened every Wednesday evening in the summer. “Roads are good, the canyon lovely, eats for the hungry, sweets for everybody,” read the advertisements. Guests could dance, get a meal, and grab a cot for the night, all for $1.50.

The Pines, a dance hall on Badger Creek eight miles north of Driggs, touted “Good Food and Good Music.” Pincock’s Hot Springs—today’s Green Canyon Hot Springs on Canyon Creek—offered dancing and a soak in warm mineral water at a time when bathing was neither a regular nor common occurrence.

Victor’s Log Cabin Inn, dance haven and watering hole, served whiskey to anyone

tall enough to push a quarter over the bar. Beesley’s Hall in Driggs, LDS ward houses from Victor to Haden, and two high schools rounded out the dozens of dance floors available.

The annual dance menu burgeoned with choices. Dress-up dances like Days of ’49, Gold and Green Balls, Grand Balls, Masquerade Balls, and Pioneer Balls, mixed in with Rose Proms and Junior Proms, warranted splurging on a two-bit haircut at Cordon’s Barber Shop to complement an $8.00 suit from Sewells’ Mercantile. Brand-new $695 Chevrolets from Choules Motors dotted the parking lots at dances of every stripe, ranging from the informal to wedding, fundraiser, and missionary farewell dances. New Year’s Eve, Valentine’s Day, St. Patrick’s Day, Fourth of July, July 24th (an LDS holiday), Veterans Day, Halloween, Thanksgiving, and Christmas provided additional reasons to rosin up a Teton Basin bow.

Utah Mormons arrived in the waning years of the 19th century with violins, guitars, mouth harps, banjos, and harmonicas stashed under their wagon seats and English, Scottish, and Scandinavian musical blood coursing in their veins. The James Frederick Stone, Ebenezer Beesley Jr., and Richard Drake families fueled Teton Valley’s insatiable appetite for live music at a time when there was no other kind.

Fred Stone, Chapin Ward chorister, fashioned a violin from a cigar box; accompanied by his tunefully talented children strumming guitars, picking mandolins, and blowing into saxophones, he launched the locally renowned Stone Orchestra.

Beesley, a gifted fiddler known as “Eb,” when not playing with family members teamed with school music teacher James Griggs on piano and Biz Green playing trumpet. Loading an old Estey organ into a horse-drawn buggy in summer and a covered sleigh in winter, the three-piece band hit the dance-hall road. “Grandpa Eb would play the fiddle, dance, and call dance directions simultaneously,” recalls his granddaughter,

Vernita Meikle. “He could write the different parts of music for his orchestra as fast as one can write a letter.”

Richard Drake brought an organ, two violins, a harmonica, and a musically gifted family into Bates Ward. With sons sawing violins and daughters chording on pianos, the Drake Fiddlers favored the south end of the valley with their dance music. Son Ted Drake and his kids kept the family band playing long after Richard hung up his fiddle. Ted, according to Teton Valley News editor and manager C.G. Campbell, knew how to fiddle more old-time tunes than any man this side of the Bingham County line. Hearing that Drake would be playing for a dance in Cedron, the editor wrote in the newspaper that he would attend even if he had to “break the shinbone in his right for’d foot” to get there.

Pleasant Monroe Sherman, a multiinstrument talent proficient on fiddle, guitar, mandolin, zither, banjo, piano, and organ, rode into the valley from the Midwest. “Plez” found constant work with the Drake, Stone, and Beesley bands. Time’s odometer rolled over a fresh century. The two-step replaced quadrille and reel dances. The hugely popular two-step, from John Phillip Sousa and his 1891 “Washington Post March,” featured a quick–quick slow step, followed by a sideways or forward skip. And waltzing, once considered vulgar and sinful, whirled into respectability.

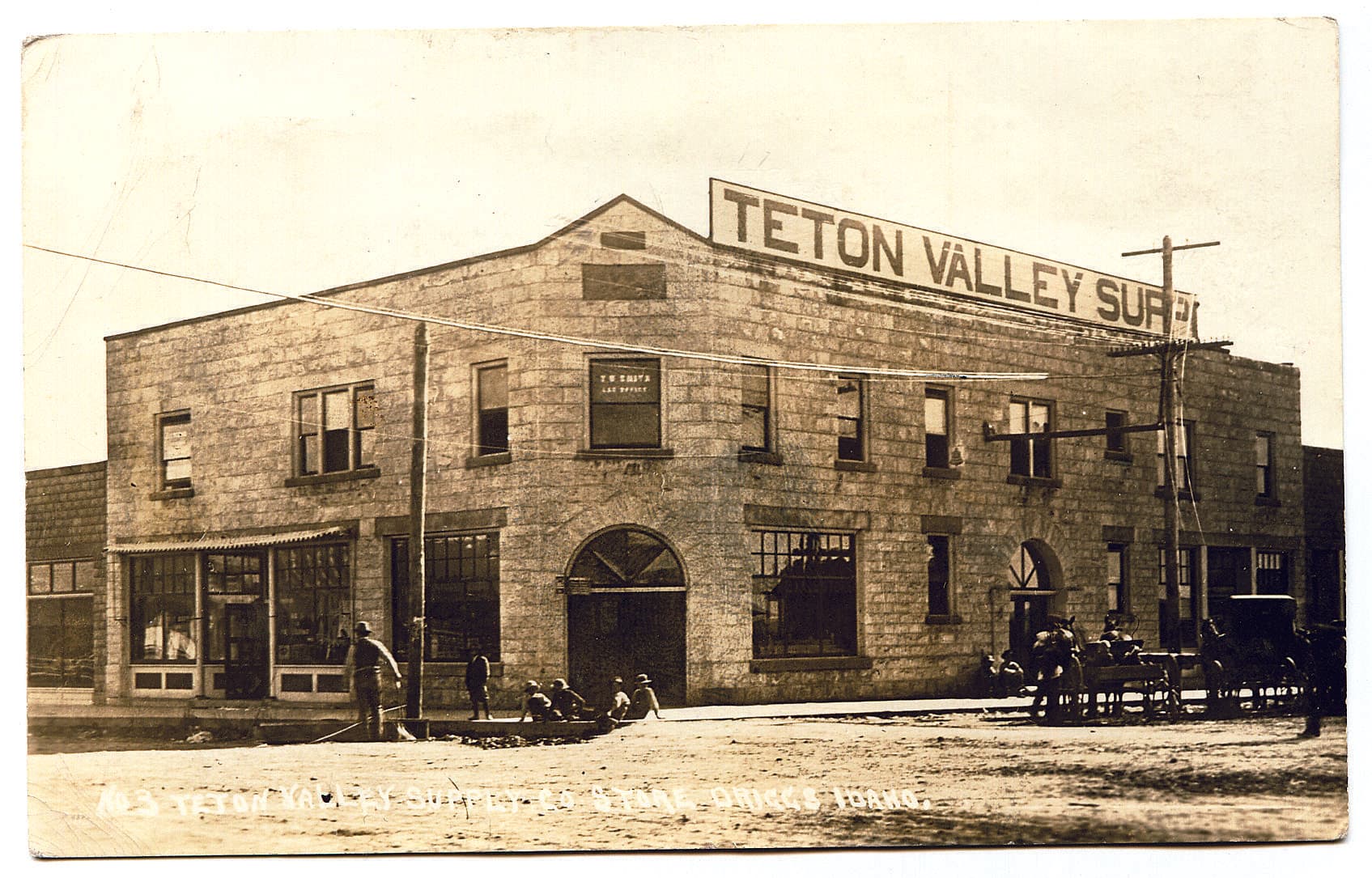

Picture a dance hall, instead of a bank, on the northeast corner of Main and Little in Driggs. Civic leaders offered the free choice corner lot to Eb Beesley in 1909, provided he build a dance hall. Eb seized the offer; after all, city lots were fetching from $50 to $175 apiece.

“Grandpa and Charles Carr built an octagon-shaped pavilion a little east of the corner,” says Vernita Meikle. “Later on, the pavilion was torn down and a two-story building was erected on the corner, with the dance hall on the upper floor and the lower floor used for business.” Shoemaker Eb, ever the entrepreneur, repaired shoes worn thin from dancing to his music in his hall. A running ad in the newspaper proclaimed: “Beesley, The Handy Man— repairs your shoes, hangs your paper, or plays for your wedding.” For three decades the Beesley’s Hall maple floor, lugged in by a team of horses from out below, seldom cooled. A Mecca for merriment, Beesley’s beamed a siren song throughout the valley. A typical night might be a boxing match, a fencing match, a wrestling match, gymnastic demonstrations, and two basketball games between Victor and Driggs men, followed by a dance with Eb Beesley’s

Orchestra, all for 25 cents. Eb’s wife, Emily Jane, who raised turkeys, sold turkey suppers and pies to patrons neglecting to bring a midnight snack, after which dancing resumed until dawn. The boys came back from over there after World War I to find people motorized. Cars replaced the front porch as courting grounds, encouraged wider roaming about the valley, and regularly emptied homes and filled local dance halls.

The social revolution sweeping the country brought new sounds and energy to Teton Valley. Movies learned to talk. Banned booze abounded; women voted and smoked in public. Hemlines rose, inhibitions dropped. Above-the-knee skirts, bobbed hair, bound bodices, and rolled stockings shocked those born in the previous century. Sans girdles, women in loose flapping dresses, fringed and beaded, jiggled and shimmied freely.

Out at The Pines on Badger Creek the trees vibrated as “Flappers” did the “Shimmy” to the upbeat, bouncy pitch of the drums, cornets, trombones, clarinets, and caterwauling saxophones of the Heimies Band, “The Band That Satisfies.” Body movements heretofore never seen—the wild free shaking of the behind, vibrating shoulders, and leaps into the air—appalled many.

The new body gyrations spawned the animal dances: the Turkey Trot, Grizzly Bear, Kangaroo Hop, Monkey Musk, Duck Waddle, Bunny Hug, Chicken Scratch, Squirrel, Horse Trot, and Camel Walk. Outraged, the predominantly church-going community reacted. Ordinance number 45, “for the prohibition of indecent and immoral dancing…evil in its tendency,” was signed into law August 8, 1919. Specifically, the Rag, “Chimmying,” and the Bunny Hug, if performed within the corporate limits of the Village of Driggs, carried a $5.00 to $50.00 fine. Any firm, company, society, or person owning, leasing, or having charge of a dance hall where the dances were held was subject to the fine.

A few years later, Mr. C. L. Luke, Teton High School physical education and music teacher, tightened the standards at school dances. Students balked. “I am in favor of [dance] reform, but I am not in favor of rules which compel me to dance like my grandmother,” wrote an anonymous Teton High School student in the local paper. “If Mr. Luke thinks he is going to change my dancing he’s mistaken.”

New dances sprouted faster than they could be banned. Around the valley, the Black Bottom, Rag, Knickerbocker, Castle Walk, Harvard, Peabody, and Fox Trot dominated dance floors. Young people returned from the A.C. [Agricultural College, now Utah State University] “doin’ the Raccoon.” Couples were no longer necessary; dancers could now perform solo. Swiveling feet, and hands crossing back and forth on knees as they fanned in and out, formed the signature dance of the decade, the Charleston. Beesley’s Hall, the hottest place to spend a Saturday night and 75 cents, boasted “Snappy Music, Punch, and Water, and a Good Time For All.”

Crash went the stock market in 1929, squelching the roar of the Twenties. “Ain’t We Got Fun” gave way to “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” Inhibitions rose, hemlines fell. Short flapper dresses went into mothballs and female legs back into hiding. The Depression’s pedestrian pace of life commandeered the dance floor; jobs were few and money scarce, but dances plentiful. At Beesley’s Hall during the 1930s, a bevy of bands kept feet shuffling along to a languid beat. The waltz, back in favor again, and the Fox Trot, the only animal-dance survivor, were the moves of choice.

The Mike “O” Lodians shared regular Saturday night gigs at Beesley’s with a band from Victor known as The Victorians, Leland Christensen and his Orchestra, Ern Hill and the Boys, The Harmonicans, Glenn Hammond’s Nine-Piece, Ross Parkinson’s Band, the Egbert-Benson Orchestra, and the alluring melodies of the Rhythm Aces. Ted Drake closed out 1933 at a Daughters of the Utah Pioneers New Year’s Eve dance for “all married folks, widows, bachelors, and old maids of the valley.”

Admission: 50 cents. Out in the hinterland, at the weekly dances and frequent special-event dances in LDS ward basements and cultural halls, multi-aged crowds dipped and turned to the sounds of the Clarence Murdock Orchestra’s “Star Dust,” “Stormy Weather,” “Blue Moon,” “Moon Glow,” and the number-one song of 1935—the “Nine Don’ts of Dancing” notwithstanding—“Cheek to Cheek.”

Equally ubiquitous on the valley dance scene in the ’30s and ’40s was a new generation of musical Stones: Russell, Elmer, and Dwight, continuing the Stone Orchestra legacy. Often teaming with Milo and Iris Dalley as the Stone/Dalley Orchestra, they attracted large crowds wherever they played.

The Dalleys featured Milo on banjo and guitar, Iris on piano, and Warren Huff ’s drums. They kept Pratt Ward on dancing toes every Saturday night for years. Phil Sorensen, who was born in Alta in 1925 and passed away in 2004, recalled horses and sleighs lined and tied up to the fence posts. “Most of the kids and adults attended and mixed together.

We always knew we could go and have a fun time on Saturday night. When the dance ended at midnight, those who were a little less righteous went to the Log Cabin or Timberline in Victor to dance the rest of the night away.”

Pre-baby boomers and valley natives who remember two-digit telephone numbers will tell you the most elegantly elaborate dancing affairs were the Gold and Green Balls, once ubiquitous in LDS wards. Lavish decorations, floorshows, and the finest bands available provided unforgettable formal dances, as close to royal affairs as Teton Valley ever saw. Each ward held a Gold and Green Ball, culminating in a gala Teton Stake Gold and Green Ball. Reportedly, the 1932 Driggs Ward Gold and Green Ball drew the largest crowd ever to Beesley’s Hall.

Dance cards were de rigueur at most dances. Couples, cards in hand, circulated about the hall choosing partners for dance exchanges. The card, actually a two-page booklet, spun an imaginary tale about the event, with spaces left blank for names. The orchestra announced the number of each dance; checking their cards, people would seek out their partner for the next dance.

“We all learned to dance very young in Teton Basin,” Lois Penfold Moss, born in Darby in 1916, often told her children.

“Usually we started learning in Primary (LDS Church) and then in school we had our first nice dance in the fourth grade on Valentine’s Day. We dressed in our best and had manner lessons. We made our dance cards and filled them out ahead of time with a different partner for every dance. As we got older, we were permitted to have a special someone on the first, middle, and last dance.”

The Depression years gave way to another war, and dancing again took an athletic turn. Blending speed, energy, agility, and enthusiasm, the Jitterbug ironically had former flappers—older if not wiser—shaking heads at the aerobic acrobatics of dancers. Down at Beesley’s Hall, airborne variations, dubbed the Lindy Hop after Charles Lindberg, lifted, spun, and tossed wildly many of today’s valley great-grandmothers.

Post war, the dance of the year, the New Year’s Eve Fireman’s Ball, would fill the Teton High School gymnasium with over 500 people. “Get hot with the firemen,” read the newspaper ads. Murdock’s six-piece band dolloped huge helpings of “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,”

“Chasing Shadows,” “Lullaby of Broadway,” and “Red Sails in the Sunset.” Legs began to ache and liquor began to talk.

“The old and young, drinkers and nondrinkers, all attended and danced until morning,” recalled Phil Sorensen. “Well, some of the drinkers danced and then fought until morning.”

“But they always fought outside,” added Phil’s wife, Carol. “So, it was acceptable for my friends and me to go. We were taught to not turn a fellow down if he asked us to dance, except if he was drinking, then it was okay to say ‘no.’”

Teton Valley dancing momentum peaked around mid-century and then faded slowly. In September 1949 five dance ads ran on the local newspaper’s front page: the Bates Gold and Green Ball, the Dipsey Doodlers all-girl orchestra at the Timberline, the Autumn Festival Dance in Driggs, the Barn Dance (a library fundraiser at Teton High), and Tetonia’s Harvest Ball. Ten years later, only the Timberline offered regular dancing to live music.

Changing tastes in music and dancing led to the demise of the Gold and Green Balls. An article in the LDS Church News lamented the difficulty of putting on a dance that appealed to both adults and youth. Proms and high school dances alienated adults with rock ’n’ roll and the Twist. Dance bands disbanded, replaced by DJs spinning records. Mom and Pop no longer danced the polka, but watched it on “The Lawrence Welk Show.” The tube became a Saturday night companion, siphoning off dance attendance. Young people watched dancing on “American Bandstand” every day after school. Dance participants turned into dance spectators. Dance venues disappeared. Victor High School burned down in 1940 and Beesley’s Hall burned two years later. A 1940 chair-busting, bare-fisted donnybrook destroyed Victor’s Log Cabin Inn. The site of the Smith’s Auto Court outdoor dance pavilion is now a Forest Service campground. Church reorganization and consolidation dissolved wards, leaving deserted dance floors in Felt, Haden, Leigh, Bates, Pratt, Darby, and Cedron. Today, where the Badger Opera House once stood, cattle munch grass. Every dance that was to happen there has happened, and most everyone who might remember them is gone.

Nothing remains but an echo of the Badger Quadrille and a ghostly call for fiddlers to sound their A string.