What’s in a Name?

On a recent journey through Montana, I met a woman who had lived in Idaho Falls 20 years ago. We got into a conversation about skiing, and she inquired about our local ski hill.

“Targhee,” I said.

“Yes, but back in the day that I used to ski there, we called it something else.”

“The Ghee?” I asked, referring to one of the local nicknames for the resort.

“No, no, some person’s name…what is that…Fred’s yes, yes, it was always referred to as Fred’s Mountain when I skied there.”

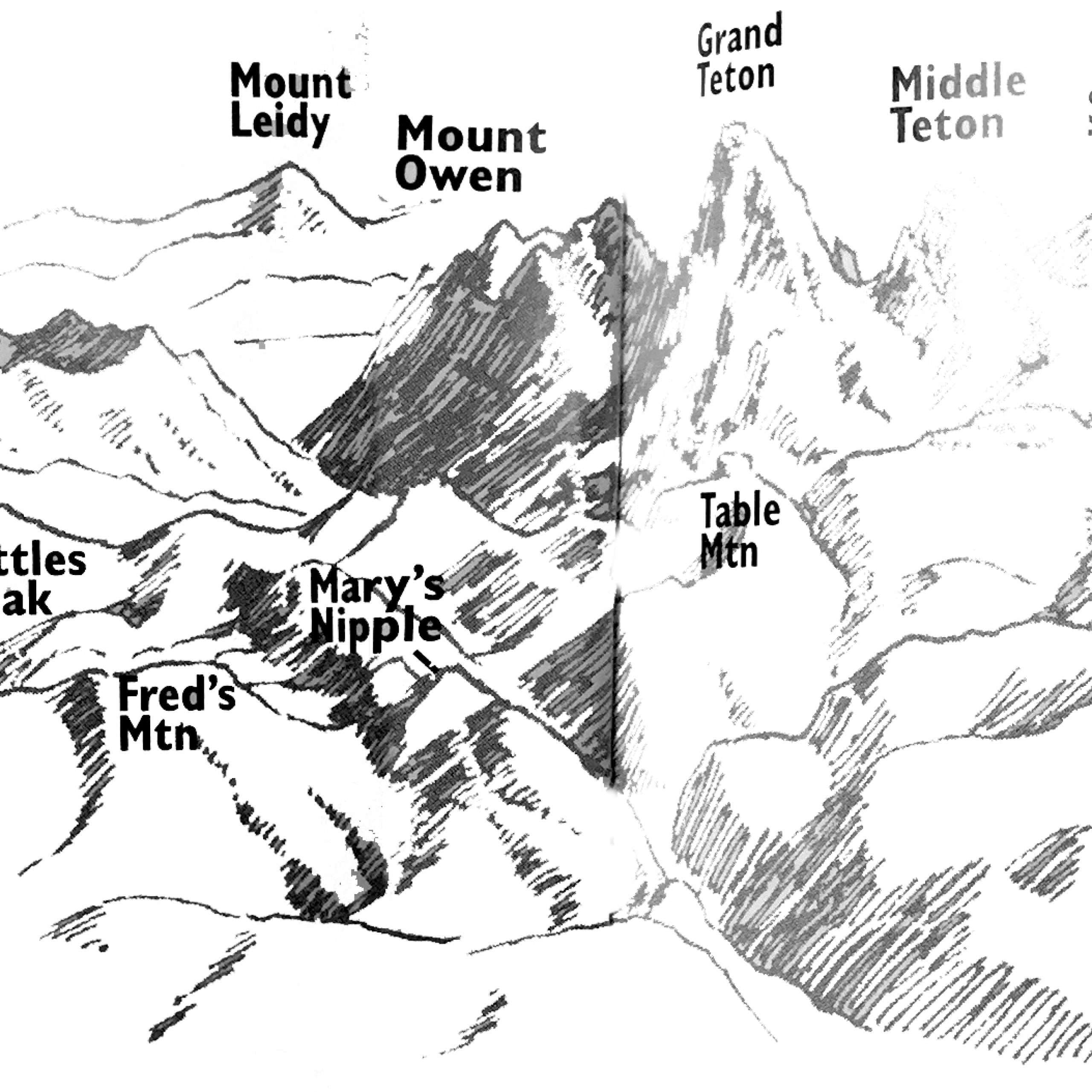

Indeed, on the United States Geological Survey topographical map for the area, the mountain with the ski lift marked to the summit is called Fred’s Mountain. Fred isn’t a relative of the Bannock leader from whom the resort takes its name or some amazing skier who discovered every run on the mountain. Fred’s Mountain is not named after a local retailer or a local resident, for that matter. Fred was Fred Clark, a member of Ferdinand Hayden’s geological survey of 1872, which put the west slope of the Tetons on the map, literally.

Hayden, a government geologist, guided the surveying of most of the West over an eight-year period, documenting the wealth of resources the government had acquired in the westward expansion. Members of his survey crew were much more than just map makers. They were the early explorers at a time when no roads or marked trails existed. They were the pioneers of bushwhacking, perhaps the first to summit a peak or ford a river. Their job was to bring identity to anonymous lands.

According to Elizabeth Wied Hayden and Cynthia Neilsen, authors of Origins, A Guide to the Place Names of Grand Teton National Park and the Surrounding Area, it was during the 1872 survey that many of the mountains, creeks and lakes in the Teton region acquired recorded names, including Teton Pass. Bradley Lake in Grand Teton National Park is named for Hayden’s chief geologist during the 1872 survey, Frank H. Bradley. Nearby Taggart Lake is named for Bradley’s assistant, W. Rush Taggart. Joseph Leidy, for whom Mt. Leidy is named, was the paleontologist for the survey.

By this time, Les Trois Tetons, a name coined by French fur trappers that translates into the three breasts, and the Pilot Knobs, a name alluding to the peaks’ visibility as landmarks for many miles, were already common references for the main summits. However, in Hayden’s Sixth Annual Report for the region, Bradley recommended the Grand Teton be called Mt. Hayden to honor his leader. Hayden, in his humbleness, felt the Grand Teton was a more appropriate name for the 13,770-foot peak and wanted it to remain. Though the Grand by any other name would stand as tall, the lure of Mt. Hayden may not have been so strong today. Few would disagree that “grand” captures the essence of the exalted center peak.

Another U.S. Geological Survey expedition led by topographer T. M. Bannon came through the region16 years after Hayden. Bannon’s crew produced the first two topographical quadrangles in the region of the Grand Teton and Mt. Leidy. In order to do this, they established a triangulation station on the 11,938-foot summit of Buck Mountain. But first they had to climb the mountain, a feat that earned them the distinction of a first ascent. On the summit, they built a 6-foot tall, highly visible cairn, or pile of rocks useful in the practice of graphically delineating the natural features of the mountains to show their relative positions and elevations for the topographical maps.

George Buck, for whom the station was named, was one of Bannon’s assistants. On 1924 maps of the Teton National Forest, Buck’s name appears on the peak. Bannon’s name is memorialized on the mountain that bears his name, the 10,966-foot peak that sits just above Death Canyon Shelf, its southeast face included in the boundary of the national park.

During those years of 1872 and 1898-1899, the surveyors not only created new names for the peaks but also recorded those already commonly in use.

Some mountain peaks memorialize eras long since past. The heyday of the fur trappers is commemorated in peaks such as the 10,610-foot Mt. Jedediah Smith, named after the well-respected fur trapper who died at 32. He was killed by Commanche Indians on the Santa Fe Trail in 1831. Joe Meek was also a trapper in the Jackson region during the 1830s. His name is remembered on Mt. Meek—which at 10,677 feet, is not so meek at all.

Several west slope peaks carry the names of early frontiersmen. Conant Peak is named for Al Conant, an early homesteader on the west slope of the Tetons. According to Richard “Beaver Dick” Leigh as reported by Hayden and Nielsen in Origins, Conant almost drowned in 1865 in the creek that now bears his name.

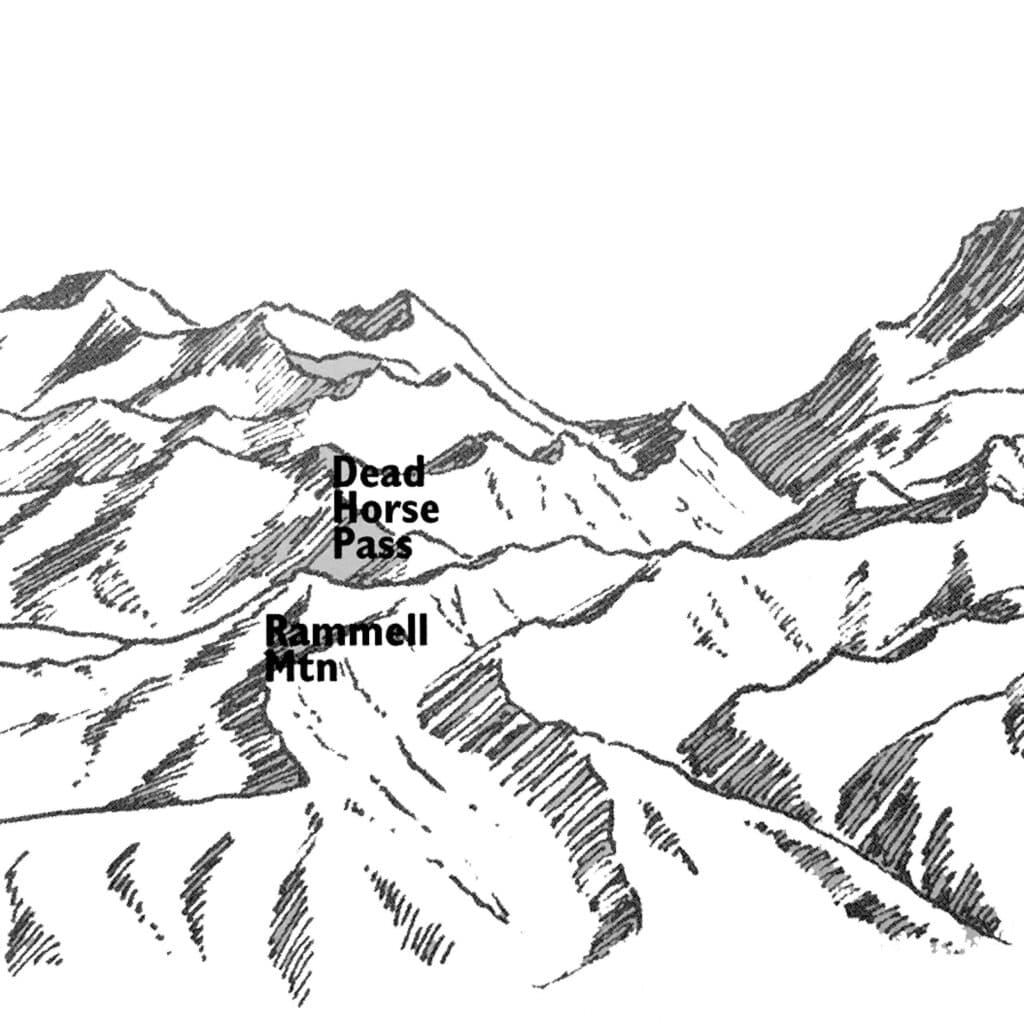

Rammell Mountain takes its name from Charles A. Rammell, the grandson of the original Rammell family that moved to Teton Valley 100 years ago this year. He was prospecting on the mountain and had a claim for a copper mine. He also operated the Brown Bear coal mine in the Big Hole Mountains on the Valley’s west side.

Beard Mountain, located to the north of Fred’s, stands for the family name of 12 brothers and sisters who made their way to South Leigh Creek via Teepee Creek from Coalville, Utah, back in the first decade of the 20th century. They operated one of the first sawmills in the region. People from all over the Valley purchased or bartered for the milled wood. A wood-fired boiler once used to power the saws still marks the location of the original mill. According to Gloria Kimball, a descendant of the original Beard family, “We were the only people up in the canyon…the mill had been there since 1910. It seemed like a natural thing to call it Beard’s Peak.

Another peak that bears a family name is that of Little’s Peak, standing at 10,712 feet just on the edge of Grand Teton National Park. Kevin Little has had the story of his family passed down to him through the generations. His great grandfather moved to the Valley in 1889 from Utah and lived in Hayden outside of Tetonia. The family took advantage of the “squatter’s rights” laws governing the Homestead Act of 1862, which granted 160 acres of land to anyone willing to live on it for five years. According to Kevin, his grandfather later turned the 160 acres into 400 acres, raising 11 children at the same time. The first ascent of Littles is credited to T.M. Bannon’s survey crew of 1898, as their maps show a benchmark on the summit.

While some peaks carry family names, others possess physical features that lend themselves to naming. Table Mountain was named as early as 1898 for its flat-topped appearance. Battleship Mountain appears aptly named when viewed from the east. Fossil Mountain, standing at 10,800 feet, has a vast array of sedimentary rocks rich in fossils. The name appeared on maps back in 1911 and helped dispel myths that there were no fossils in the Tetons.

In the southern end of the Tetons, Housetop Mountain was named as early as 1908 for its house-like figure. Nearby Baldy Knoll takes its name from a lack of vegetation. Spearhead Peak, sitting at the mouth of Fox Creek, must have been a good place to hunt mountain sheep. The name comes from the numerous spearheads found in the area.

Carrot Knoll, found much further north on the divide, is covered with wild carrots in the summer. Apparently early sheepherders allowed their stock to overgraze the area, resulting in fields of carrots, which the sheep did not like to eat. Similarly, Beard’s Wheatfield is also covered with wild carrot that, when it has died out, resembles a field of wheat growing on the limestone bench.

Deadhorse Pass to the north takes its name from the terrain. The area is a tough place for horses, so those who were trying to escape the law would use this route as it made it difficult for anyone, particularly the sheriff, to follow on horseback.

Another mountain that takes its name from a geographic feature is that of Treasure Mountain. There is no buried treasure on its summit or slopes but at sunset, the outcropping of rocks on the north side of the canyon known as the Twelve Apostles turn the colors red, hazy blue and gold, the color of a treasure. The Boy Scouts who stay at Treasure Mountain camp find their pot of gold at Chief Rock while listening to the Legends of the Tetons, a story told in the same way Vernon Strong recited it back in 1936 when the camp first started.

A second era of mountain naming came with the mountain climbers during the early 1900s. Fritiof Fryxell was Grand Teton National Park’s first ranger naturalist. Along with Phil Smith, an early homesteader in Jackson, the duo is credited with many first ascents in the Tetons. In order for them to be able to refer to the peaks in conversation, they named many that they climbed. By 1931, most of the names they gave the mountains had been approved by the government, thus putting the finishing touches on the masterpiece.

Mountaineers today can name peaks in the same spirit as the early pioneers, although they may have to cut through a little more red tape first. For information on the proper procedure or to request a petition, contact Roger Payne, executive secretary of the United States Board on Geographic Names at (703) 648-4544. Or write to him at the U.S. Geological Survey, 523 National Center, Reston, VA 20192. The board will consider strong recommendations; names shouldn’t be excessively long or controversial and must be acceptable to local citizens.

That being the case, several peaks near Fred’s Mountain could be candidates for an official name. Peak 9943 is nameless on the map but around town it is known as Mary’s Nipple. According to local rumors, the mountain takes its name from a former cocktail waitress who was part of the early 1970s streaking generation.

Similarly, many of the bowls and peaks on Teton Pass are not officially named on the maps. In the same way that the early climbers named peaks to be able to refer to them later, skiers on the pass have done the same. Their names are very descriptive: Powder Reserve, Hangover Hill, Avalanche Bowl, Triple Direct, Little Tuckerman’s. Mt. Glory is the one peak on the pass with an official name. It was named by students from the University of Michigan studying geology at the school’s Camp Davis, located on the south side of the Hoback River, who noted its “glorious appearance.”

It is hard to think of just one peak in the Tetons as having a glorious appearance; indeed, the whole range might be called glorious. But each individual name provides insight into the social history of the mountains that geology and natural history just don’t reveal.